This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

April 2009

Anthony McCall and Andrew Tyndall's 1978 film essay Argument, is many things; a deconstruction of print advertising, a critique of the dominant construction of masculinity, and a flabby, navel-gazing manifesto of frustrated ambitions, to name but a few. If its subject matter feels ever so slightly outdated, its formal strategies remain striking, none more so than its juxtaposition of sections of text and voiceover that begin in congruence before diverging at key moments.

Watching it today, however, one does get the sense that the film's purported radicalism seems tailor made to fit in and around those very aspects of masculine identity that are lacking in the lives of the artists under discussion. The choice to make art here involves the deprivation of precisely those components of upwardly mobile masculinity that are ostensibly up for reexamination. But diagram is not the same as critique, and, - perhaps this is where the film remains most disappointingly contemporary - artists today still seem to believe that its okay to want the politically retrograde so long as one understands it to be so. McCall and Tyndall seem to find no tension in demanding that the world pay a living wage for them to perform their avant-garde experiments. Which begs the question, what kind of avant-gardist expects to be well paid?

One might also wonder what the Anthony McCall of today would say to the 1978 model and vice versa. The newer version is speaking tonight, at the Whitney.

In her brief introduction to Younger than Jesus, the inaugural installment of "the New Museum's new signature triennial," called The Generational, curator Laura Hoptman remarked on the absence of a hostile generation gap between the so-called millennial generation, and those preceding it. This, we understood, was in contrast to the Baby Boomers who, it seems, never tire of reminding us as to just how oppositional they really were in their day. But not these millennials, as Massimiliano Gioni, another curator, observes, 'Rather than forswearing their parents, (these artists) seem interested in imagining new communities and alternative families.'

Perhaps this is because this is the first generation in which ‘imagining new communities and alternative families,’ does not require forswearing one’s parents. Or perhaps it is not even as clear as all that. Who was it, after all, that declared that self-conscious opposition is the essence of youth anyway? Not only Hoptman and Gioni, but Holland Cotter too seems vaguely uncomfortable, even disappointed at a show that 'feels awfully sedate and buttoned-down for a youthfest. Kids R Us it ain’t…'

Thus, no doubt, the widespread love affair with Ryan Trecartin, who, separate from anything else, conforms most readily to the older person’s idea of what it means to be young. All that volume! All that technology! All that speed! And he's on youtube! Thar be the youts, for sure. Even the obsession with describing the millenials by referencing any number of online/networking apps feels like a top-down operation. What’s more likely to stand out to an old grappling with the intricacies of Twitter than the young’s casual fluency? But this does not a generation define, it is rather only the latest metaphor for encroaching senility and onrushing impotence given a contemporary sheen.

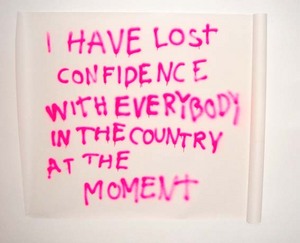

No, more troubling remains the ostensible search for opposition among the young, which dangerously underestimates the extent to which youth became a general cultural fetish during the second gilded age. What, in God’s name, does any young person have to rebel against? Only their own personal failure at not being chosen for the Generational, it would seem. Anyone moving among young artists in the weeks and days leading up to the opening of Younger Than Jesus noticed no spark of opposition, merely widespread sadness at having been considered, as many were, and not chosen; a generation defined by everybody’s desire to represent it.

This Wednesday, the Guggenheim hosts a conversation with Julieta Aranda, whose multi-part installation 'activates the museum's triangular staircase.' Included is an oversize clock that the divides the day into 10 hours, each composed of 100 minutes, each of which is similarly broken up into 100 seconds; a system briefly imposed in the zeal for rationality following the French Revolution, with one further modification. The 100 second interval is determined by the artist's own pulse rate. In this way, Aranda draw attention to the way our mood and state of mind influence our perception of the passing of time. Aranda has also used phosphorescent paint to copy quotations about time from more than two millennia worth of sources, words which only become visible at specific moments when the lights dim.

Aranda has long been concerned with the construction of time. Her work You Have No Ninth of May! concerned the International Date Line, which used to bend around a small island nation of Kirbati, that is until Kirbati decided to switch from being the end of one day to the beginning of the next. Aranda created an archive of objects and relics documenting this switch, investigating how the social construction of time allowed for an otherwise impoverished nation to claim worldwide agency.

Agency too, has been a consistent theme in her work, most notably in two collaborations with Anton Vidokle, Pawnshop, and e-flux video rental, each of which made interventions into circulation of cultural capital. The talk starts at 6:30.

On Rhizome today, Brian Droitcour publishes a brief survey of last weekend's Migrating Forms at the Anthology Film Archives, the successor to the retired New York Underground Film Festival. Meanwhile tomorrow at the X initiative space in Chelsea, Ed Halter, ten-year programming veteran for the NYUFF, will sit on a panel with curators Chrissie Iles and Stuart Comer, as well as artists Gerald Incandela and James Mackay to discuss the Super-8 films of Derek Jarman, 'a cinema of small gestures,' recently on view at X. On Sunday meanwhile, Anthology Film Archives presents their annual Essential Cinema screening of George Landow/Owen Land's early works, another filmmaker of small gestures (in a very different sense).

When the inevitable relegation of print publications to the digital ether of the interweb finally takes place numerous moments of lived experience will go extinct. In some cases - such as the floor-bound trajectory of countless subscription cards, falling, in twos and threes, out of newly received periodicals like so many airborne seedpods – this absence will be a good thing, if it is noticed at all. Others are more likely to be missed. For example, we will no longer be able to stand in front of a newsstand and survey the myriad visual strategies vying desperately for attention; still the swiftest method of adjudicating mass culture’s endless interpolation of the issues of the day. Indeed, our memories of significant events often turn out to be, upon examination, merely montages cobbled together from the images of various magazines, and we hold a special place for the uniquely well-tempered cover-shots that pierce, at moments, this constellation’s variegated history.

The financial crisis, however, has provided a problem for the great minds working in layout throughout the world. At once abstract and universal, the details of our current situation do not lend themselves, or have not yet, in any case, to being captured in any one, memorable image, or even set of images. Thus the newsstand has been treated to endless shots of piggy banks in various states of distress, downward slashing flow charts, and a great deal of big words, brightly colored – such as Newsweek’s decidedly comical “We Are All Socialists Now,” from a few months ago.

Alternative Architecture and Outlaw Design

Nils Norman and Eva Diaz

Cabinet - 300 Nevins St, Brooklyn NY

7pm Friday 24 April 2009

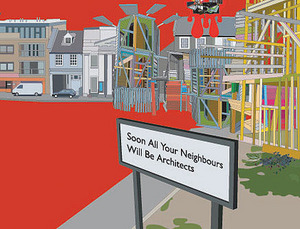

This Friday at Cabinet's Brooklyn event space, Nils Norman and Eva Diaz will be talking about Buckminster Fuller's lasting influence on contemporary architecture's encounter with housing crises and homelessness. Displaced from this influence today is much of the ideological underpinning that once informed and nurtured a resistant and pioneering spirit in both culture and politics among the intellectual malcontents of the Cold War's first few decades. This spirit or ideology today is today sometimes substituted by provisional, tactical and information-oriented engagements made necessary by an often deeply managed (commercially, legally) landscape. The talk will anticipate Norman's upcoming collaboration at SculptureCEnter, The University of Trash. From the press release:

Many people today are stimulated by Buckminster Fuller's post-war dome technologies, as well as other 1960s and 1970s-era shelter designs, to radically rethink architectural structures, both as a practical solution to urban housing crises and as a key historical trope of innovative "guerrilla" architecture. The difference today: gone is the frontiersman logic of back-to-the-land, drop-off-the-grid, atomized micro-environmentalism... What enters instead is a proposition of sculptural structures as temporary interventions in urban sites, of kiosk production and shelter-information display hybrids.

This week on Paper Monument's website Christopher Hsu contemplates the contemporary artist's relationship to work, grounding his meditation in the English-speaking artist's multivalent and frequent deployment of the word. The artist at work at once inhabits both the ideal sphere of gratuitous free action -- itself compelled by the art worker's very way of being in the world rather than some sort of compensatory system -- and at the same time a slightly distorted leftist legacy of creative or intellectual production aligned with its material or industrial counterpart. Even my own language here belies the pervasive entrenchment of this model -- how does one describe something as usefully ambiguous as cultural production without resorting to the language of industry?

Benjamin frames the affinity of the intellectual or the artist for the work of the proletariat class as a politically strategic relation, but we see its prototype even earlier when Marx postulates in the Theses on Fuerbach that the "philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it." To change the world is to work -- to move from contemplation, to action, transforming the material, data, or social relations undergoing that action. The bifurcation of art from craft meanwhile -- of expert work and art work -- signals a means of action polar to the means of that action's intended effect. The contemporary artist, Hsu suggests, in her aggressive affirmation of her life's work, obfuscates the more deeply rooted and deliberate relationship to leisure at the core of her being in the world.

Paintings and Pots

Sarah Crowner

Nicelle Beauchene Gallery - 165 Eldridge

26 March - 3 May 2009

Familiar New York soot thinly coated the bone-dry, paper-white surfaces of Sarah Crowner’s misshapen natura-morta rendered three-dimensional. Her decision to place five white vessel sculptures in the shoulder-high window of Nicelle Beauchene Gallery seemed particularly strange at first. However, this earnest arrangement begins a dialogue between art histories through a quiet re-contextualization of medium specificity. Paintings and Pots, the title of Crowner’s first solo exhibition, would come to seem mostly inaccurate.

Two other groupings of endearingly crude, achromatic vases also ignore carefully balanced tone and composition in the referred still-life paintings of Giorgio Morandi, forbearer to the Minimalists, setting off a kind of referential play that continues within the other works on view. Crowner’s canvases, which command the show, employ a restrained palette and bring to mind the male-dominated canon of 1950s and 60s Post-Painterly Abstraction. Though unlike those surfaces, her works divide into roughly textured linen, painted canvas, and solid-colored cloth, thereby re-introducing a handmade element to the cool touch in painting by figures such as Ellsworth Kelly. In two acute compositions, both titled Dichromatic Organization, 1959 (2009), a tension vibrates between the pictorial and physical components. The accelerating, triangular slices found in the work of Swedish painter, Olle Baertling (1911-1981, explicitly referenced in press materials) are sewn together by Crowner in a manner reminiscent of Miriam Shapiro’s (1923–) innovative fabric-and-canvas assemblages. Shapiro, a forerunner of the Pattern and Decoration Movement, began her career as a hard-edge painter.

Crowner’s canvases also piece together, and in some cases seem to pull-apart the gendered concepts of craft and high-art while joining the delimited surfaces within slick, hard-edge painting. Her use of a sewing machine evokes obvious notions of “women’s work,” while the substitution of cloth for paint returns the viewer’s gaze, checked: where one normally expects to see paint, a seemingly flat and more illusionist, yet tactile, fabric comes into focus. Crowner succeeds in historically grounding two disparate eras, but are the resulting objects a reconciliation or reclamation? How and in what ways do we distinguish art from craft, and which artists bothered to ask such questions?

Two events investigating identity and truth are on offer for tomorrow. The first is the opening of Surveillance from the Dollhouse, a group show at Mireille Mosler. Fastening a "convergence of drawing and puppet animation by five consummate female artists," Surveillance... investigates the construction of identity via works that span almost three decades. Puppetry has long been fertile ground for such questions, bringing to visceral life questions about power, control and movement. In addition, this exhbition is an opportunity to see video work by Nathania Rubin, Cindy Sherman, Laurie Simmons, and Karen Yasinsky, artists not typically known for the medium.

Even further uptown, Thomas Demand is speaking at Columbia tomorrow evening. Demand has long been a connoisseur of construction, fabricating massive installations made from paper and cardboard for the purposes of photographing them. Demand's photos call attention to the specific details we rely on to adjudicate representation into the real and the false. Thus, in his very obsession with detail, he pushes the real farther and farther away, as smaller and smaller intricacies reveal his fabrications for what they are Demand's talk is called Fact, Fiction and Fabrication.

Elsewhere, Walid Raad was among those honored with a Guggenheim Fellowship. Raad's work has long been at the forefront of the intersection of history, representation and the archive, spanning across media and authorial guise.

Transfers: Three Works by Seth Price

Tuesday, April 14, 2009 at 7:30pm, $7

Light Industry - 220 36th Street, 5th Floor, Brooklyn

Early in his landmark essay Dispersion, from 2002, Seth Price makes the following remark, "More than anyone else, artists of the last one-hundred years have wrestled with [the] trauma of context, but theirs is a struggle which fundamentally takes place within the art system." It's a wonderful turn of phrase, 'the trauma of context,' begging a whole host of questions about the fate of the conceptual project, which Price proceeds to unpack in his own insightful, scattershot way over the course of the text. Price's point in the above quote is relatively straightforward: context is only traumatic within the artworld, and, following, the various avant-ist spasms and denunciations rely on that system's clear demarcation to scan as such in the first place, less they simply disperse into nothing. He recalls Duchamp's failed attempts to sell toys of his own designing at an amateur inventor's fair, his objects rendered uninteresting outside of their oppositional orbit.

Price's own artistic practice has spanned many contexts. Tomorrow, Light Industry will screen three of his video works, spanning twelve years of his career. The first, Sub Accident, is an investigation of images and their fraught relations with history. The second, Redistribution being screened for only the second time, takes up Price's concern with disciplinary fidelity and supplementation explored in Dispersion. Acting as a sort of ongoing, open-ended document, of the kind favored by conceptual artistic practice, Redistribution was initially designed to be view in the context of Price's own art exhibitions. The third film highlights another thread from Dispersion, namely that, despite working through many of the same problems and issues, conceptual film has often not been privy to conversations taking place within conceptual art.

Tomorrow e-flux inaugurates its expanded downtown space with the opening of Unbuilt Roads, a new exhibition presented by Hans Ulrich Obrist. The show will function as an archive of unrealized artists projects and presents a companion exhibition to Obrist's 1997 book of the same title. Aggregating a set of orphaned or impossible projects, the exhibition seeks to mobilize a phantom and heterogeneous collectivity operating on a field of speculative reason and non-action. Whereas artistic agency may often be conceived as deliberate action founded on the contingent power of symbolic acts, the unrealized action then becomes a denser consolidation of that agency, divorced from the enabling or inhibiting potential of resources, exhibition opportunities and public access and opinion.

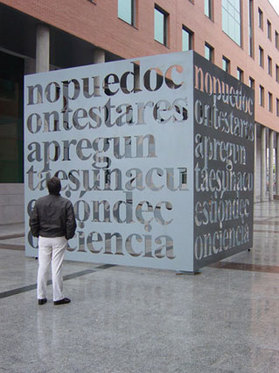

Also tomorrow is the fifth of six events accompanying On Certainty, a group exhibition and program curated by Sreshta Rit Premnath. At 3pm, legal scholar Lawrence Liang will present a paper at Bos Pecia gallery on the cultural and legal history of truth-making technologies -- lie detectors, narco analysis, focused and deliberate interrogation techniques and so on -- that have made a radical reemergence in both the popular imagination and law enforcement practice since 9/11. At the New School, meanwhile (as of today under student occupation, again) n+1 editor Mark Grief and several others host a panel titled What was the hipster?. And finally in Brooklyn, Vera List Center director Carin Kuoni will moderate a discussion at Smack Mellon between photographer Susan Meiselas and recent Guggenheim Fellow Carlos Motta as they discuss the documentary tendency in art making and, in particular, in Motta's project The Good Life, recently presented in New York at Creative Time's Democracy in America, Convergence Center exhibition at the Park Avenue Armory last fall.

When Mark Essen first started designing video games in high school, he never anticipated that it would make him a name in the art world. Now, not so many years later, Essen is the second youngest artist in the New Museum’s Younger Than Jesus show (limited, of course, to artists under 33) and one of the fastest rising stars in the growing field of video game art. Known for his Atari-inspired designs and black-humor-driven plots, Essen’s games take a page from the 8-bit games of 80s and build on them, adding new aesthetic and thematic layers to cultural objects still ripe with associations of parents’ basements and misspent youth. Creating games that are both frustratingly difficult and undeniably addictive, Essen is a gamer’s designer, a programmer whose format is deceptively simple while the logic behind them isn’t. For those not weaned on the mushrooms of Mario or the asteroid belts of Starfox, Essen’s work may seem to come out of left field, but as the Younger Than Jesus subway ads say, “This is the voice of a generation. Some translation required.” --J.L.

Jessica Loudis for ArtCat: You studied with several filmmakers while you were a student at Bard. Is there a connection between cinema and video games?

Mark Essen: There’s certainly a visual connection, and there’s also a social connection sometimes, like when you get a new game and sit down with it or you’re watching a film for the first time you’re kind of lost at first, trying to grasp the logic of the storytelling or experience. I don’t know if that makes them that related; you could say the same thing about music. I guess the major connection is that both games and films are presented in a similar way, but the role of the audience is different to each. In a movie maybe you’re trying to get into the mind of the director or whatever, in a game you’re thinking about that, the designer, and also the guy playing. Maybe you’re playing too. It’s a process of trying to figure out what the other guy’s thinking.

AC: How do you think difficulty affects the way people perform or interact with your games?

ME: There’s a lot of repetition, so it becomes an endurance test in a way. Punishment 2 is an example of this. At every level you need to go to the top of that level, and at every new level you have to go to the bottom of a tower. So it’s up, down, up, down and on each screen you’re dying fifty times before you beat it, before you can advance. It’s not very fun, I guess. It’s a test of will. If you’re playing the game alone at home it’s just masochistic, but if you go to a party and sit down with someone it becomes cooperative. It takes two hours, maybe, for newcomers to get all the way through it. Meanwhile, a crowd is watching you, they’re coming and going, and you’re on stage.

Towers and Portals

Rachel Beach

7 March - 12 April 2009

Show has been extended

Towers and Portals, at Like the Spice Gallery, is Rachel Beach's second solo exhibition in New York. Beach's seductive sculpture-paintings are postmodern, playful explorations of relativistic perception. Using oil paint and a technique called veneered marquetry, the artist creates trompe-l'oeil forms that easily segue from a two-dimensional to a three-dimensional reading and likewise maneuver between ornamentation and cleverly subversive commentary. Remarkably, the works are as sincere as they are arch.

Impressed with her previous solo effort, Chicken & Egg, at HQ Gallery, I worried that Towers and Portals might evidence a sophomore slump. Happily, Beach avoids that pitfall. Although this nit-picky viewer did notice two instances of hurried handiwork -- some uneven paint on the exhibition centerpiece, The Mothership, and stray paint spotting above Benevolent Universe (yellow and pink) - the large and varied collection of sculptural works on hand at Like the Spice is generally first-rate. In fact, it was Beach's superior craft that compelled me to search for defects in the first place.

According to our sources, David Yassky’s office is moving full steam ahead with the India Street mural project. Thanks to a seed donation of $8,000, the North Brooklyn Public Art Coalition is now accepting proposals for the huge concrete wall in between West Street and the East River in Greenpoint. The building is slated for demolition in Fall 2009, but in the meantime, NBPAC is eager to infuse the space with some public art. There are eleven artists, teachers, and even some India Street residents on Yassky’s panel. It’s a fairly open ended project, but they are looking specifically for art that celebrates arts in the community, so you’ll get points with panel members for keeping proposals family friendly. Still interested? Submission guidelines and applications are available here.

But hurry! Applications are due April 24th.

Rami Metal, from David Yassky’s office, who headed up the second NBPAC meeting, called the India Street mural initiative, “a kickoff project for the coalition…which will hopefully snowball into a lot more public art projects in the future.” So if murals aren’t your thing, feel free to contact Rami and NBPAC with a different proposal. Based on those attending tonight’s NBPAC meeting, the coalition is interested in anything from sound art to dance performances, as long as its accessible to the public, located in North Brooklyn, and, well, free. More info at Greenpointers, here.

Without

Meleko Mokgosi & Matthew Watson, Without

Work - 65 Union Street, Brooklyn NY

27 March 27 - 20 April 2009

Without, an intimate exhibition of new works by Matthew Watson and Meleko Mokgosi at WORK Gallery, toys with the definition of its seemingly simple preposition. Usually implying an absence or lack, in its most archaic form it connotes the external. It is there, in the negotiation of topical superficialities with self-identification and cultural expectations, that these two very different artists meet conceptually. In their hands, paint itself becomes a metaphor for experience.

With aristocratic portraiture as his touchstone, Watson’s images of Brooklyn locals demonstrate a true art historical praxis but with a twist. The Greenpoint immigrant of Untitled Portrait lacked even the basic English skills to share his name or identify himself — really to fulfill even the essential purpose of a portrait. The closely cropped composition and decontextualized background makes the grotesque surface of his splotchy, red face the lone signifier of his identity. Appearing to suffer from the side-effects of heavy alcohol consumption in the form of extreme rosacea and severely damaged capillaries he fulfills the stereotype of a drunken, lethargic immigrant.

Steeped in the methods and materials of Old Masters, Watson’s process counters this presumption in subtle ways. Over a period of months, he meticulously layered oil paint mixed with powdered Venetian glass and fir balsams upon a copper plate, an extremely labor-intense medium. Watson’s large investment of time and materials upends the value system of a society that marginalizes its newest members, while the very choice of a marginalized, undervalued subject undercuts the fetishization of the art object.

The Guggenheim museum recently announced the launch of Intervals, a new experimental programming series that will "allow the museum to respond quickly to innovations and new developments in contemporary art as they arise." The museum further sets an exciting tone for the upcoming series by selecting Julieta Aranda to install four new works across two of the museum's floors for its inaugural exhibition. Downtown, the New Museum prepares for next week's opening of Younger than Jesus, the institution's recently conceived generational triennial. Of the many ancillary events planned during the course of the exhibition the first discussion -- the irreverently (or cynically) titled panel Communism Never Happened -- is slated to bring together a group of Eastern European participants in the exhibition to reflect on coming of age in recently economically liberalized markets. Migrating Forms meanwhile has published the schedule for their 2009 film and video festival at the Anthology Film Archives beginning in two weeks. The program presents new feature-length work in a familiar festival format from Owen Land (his first film in over a decade) and Michael Gitlin, as well as features from Sharon Lockhart, Amie Siegel, Oksana Bulgakowa, and others.

E-flux just last week announced Unbuild Roads, a new exhibition curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist at it's Lower East Side location, marking the start a series of exhibitions and events at e-flux's newly opened lower level. Some weeks ago, a panel discussion on publishing and art journals was organized by e-flux at the same location.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian