This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

January 2008

Writing in Art on Paper on the occasion of Marcia Tucker’s death, Dan Cameron had this to say about the late curator:

Marcia set a high ethical standard for herself and challenged the art world to follow suit. She always championed the underdog, struggled to articulate art's power to change people's lives, openly deplored the growing commercialization of the New York art community, wholeheartedly rejected the current trend of running museums like corporations, and believed fervently that museum curators should maintain a healthy distance from big-name art dealers. Even if Marcia's principles are no longer pragmatic for running a museum in the twenty-first century, they may yet survive as the perfect blueprint for launching one.

I am interested here in Cameron’s contrast between running a museum and launching one, as the opening of the New New Museum late last year seems to fall somewhere in between. Not quite business as usual, certainly, but also not a totally fresh start, the dual opening — of the architecture and the art — poses an unique opportunity for a re-examination of the relationship between the current presentation and its institutional history. Which New Museum is it that opened on the Bowery to so much fanfare?

I do not wish to speculate as to whether or not the New New Museum (NNM) lives up to the ethical paradigm ascribed to Tucker by Cameron, if, that is, its launching as a new building is enough to overcome the pragmatic considerations he cites. I’m certain I have no idea; Tucker’s principles could be enumerated, commandment-style, on every new cubicle wall, or mentioning her name could be tantamount to treason, each are equally probable, for all I know, and the truth is probably somewhere in between. What is fascinating is that regardless of the relative importance of these ideas in terms of organizational or pragmatic priority, their legacy can be examined via the considerable branding effort being put forth at every level of the event in question.

We could therefore frame this another way, as a comparison of two blueprints, on the one hand, there is the one already mentioned, attributed by Cameron to Tucker, and the launching of the New Museum, and on the other, there is the brand identity created for the launch of the New New Museum. My claim is twofold, first that both blueprints are organized by, or participate in a certain discourse of authenticity, and, secondly, the appearance of this vocabulary in two distinct aspects of the NNM provide a rare window onto the lexical or symbolic relationship between authenticity as a brand, and a history of authenticity, we might say. Taken apart, neither moment is news; authenticity has been the dominant branding motif for at least fifteen years and, on verso at least, the moral paradigm of choice since the Second World War. Similarly, we have plenty of examples of people, ideas, or institutions who arrive from the past couched in a narrative of having been authentic, if sometimes little else. What is new is that the New Museum (NM), unlike Jeep, Sprite or any other brand offering itself as an emissary of the real, actually possesses a history worthy of the term. And it is a history that it has been careful to honor in terms of the design and execution of its new building and inaugural show. It is in light of this that I would like to suggest one further point, namely that the NNM may be the best example we have so far of the becoming-brand of authenticity, if only because that is quite literally what is taking place, literally the translation of one blueprint into another, as opposed to either the performative contradiction of being told to obey one’s thirst, or pulling a CBGB and never really trying.

Alex Hubbard at Nicole Klagsbrun

Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery – 526 W. 26 St, #213, New York NY

17 January – 16 February 2008

"...the genius of comedy was the same with that of tragedy, and that the true artist in tragedy was an artist in comedy also." --Plato, The Symposium

Skewering the bold ambitions of modernism has become par for the course amongst contemporary artists. Aaron Curry mixes forms from Noguchi, commercial design, and graffiti, while Banks Violette has gotten quite a bit of mileage out of mashing minimalism and death-metal nihilism. Alex Hubbard takes a much more punk rock approach with his chaotic and playfully destructive exhibition at Nicole Klagsbrun.

In a previous exhibition at the Whitney at Altria in 2006, one of Hubbard’s video works had meticulously documented the processes of a methamphetamine fabrication lab. At Klagsbrun, he turns his hand to the more abstract processes of creation and destruction with several new videos and paintings. The latter are clearly derived from the former, almost as if they were artifacts recovered from the artist's more interesting work on the two monitors installed in the gallery. A monitor across from several paintings loops three videos from the Collapse of the Expanding Field II series, while a larger monitor, in a separate room prefaced by an oil painting of floating ribbons, displays two other videos.

Cotton Candy by Ernie Gehr

MoMA - 11 West 53 Street, New York NY

8pm Friday 1 February and 5:30pm Sunday 3 February 2008

$10

Panoramas of the Moving Image: Mechanical Slides and Dissolving Views from Nineteenth-Century Magic Lantern Shows

12 September 2007 – 10 March 2008

Titus Theater 1 Lobby Gallery, T1

Titus Theater 2 Lobby Gallery, T2

American avant-garde filmmaker Ernie Gehr has been collecting various proto-cinematic devices since the 70s. The MoMA installed several of Gehr's video projections, objects, and a short text on these artifacts in the lobbies to its two Titus theatres last September, in parallel with the filmmaker's extended film retrospective at the MoMA, Ernie Gehr: Moving Image Minimalist. The projections and objects on display — video demonstrations of mechanical glass slide devices, early film "dissolve" prototypes, Zoetrope animation strips, and Phenakistiscope paper discs – were popular in the second half of the 19th century as early media entertainment forms. That Gehr has an interest in these objects and their history in relation to his own métier is consequent both to the work he has been pursuing throughout his career, as well as early cinema's dangerously perishable nature. Gehr here is managing a dual role in their presentation as both a film historian and an artist.

The early Magic Lantern artifacts demonstrated on video and hanging on the walls bear a pronounced historical weight; many of the animated figures on the Zoetrope strips, for example, feature blackface characters engaged in exaggerated movements, carnivalesque imagery of animals and fantasy creatures, a "wild Irishman" and so on — all pictures of the 19th century American "exotic." The historic narratives implied by these crude images, coupled with the austerely ingenious underlying mechanisms which animate the otherwise purely illustrative material, create a sort of hybrid narrative of cinema as a representational tool born out of the industrial revolution, and used, at least in this country, to preserve social conditions rather than aspire to revolutionize them. Seeing the projections especially is an interesting experience as three motion picture (re)presentational methodologies come to a head. The fluid character of digital imaging seamlessly encompasses the mechanical movements of these cine-toys, while the popular museum video presentation tactics of large, multi-channel projections transforms the modest animations into what even the press release unabashedly describes as "a mesmerizing wide-screen spectacle."

This weekend the Museum also hosts its final screenings of the Ernie Gehr film retrospective. The show closes rather appropriately with Cotton Candy, Gehr's first work in digital video completed in 2001. Cotton Candy is an eerie contemplation of a San Francisco mechanical amusement park in disrepair, as Gehr videotapes dejected carousel rides, mutoscope animation toys (a sort of flip book rolodex), and mechanical automatons, all existing lifelessly alongside the menacing presence of a contemporary video arcade where aggressive gameplay in amorphous virtual worlds is rewarded with the further opportunity for image consumption by the arcade's patrons.

Jacob Burckhardt at the Millenium Film Workshop

Jacob Burckhardt, Royston Scott, Jim Neu

Millenium Film Workshop – 66 E. 4 St, New York NY

8pm Saturday 2 February 2008

$8

This Saturday at the Millenium Film Workshop, New York experimental filmmaker Jacob Burckhardt presents three short collaborative works. The recent Tomorrow Always Comes (2006) and The Professor and His Improper Potion (2006), are a "film noir sex romp comedy thriller" and a silent tribute to cinema pioneer Georges Méliès adorned with various 16mm in-camera special effects, respectively. Both film were made collaboratively with film and theatre artist Royston Scott. Burckhardt will also present Duet for Spies, a 1993 film adaptation of New York dramaturge Jim Neu's play of the same title, featuring a camp narrative in which two spies are debriefed by their superiors and "can only guess at the missions, priorities and agendas behind the double-speak and double-think of their encounters."

Crafting Protest

Panel Discussion and Craft Reception

Theresa Lang Community and Student Center - 55 W. 13 St, New York NY

5pm Saturay 26 January 2008

Laurie Simmons and Sharon Lockhart at the Met

Metropolitan Museum of Art - 1000 Fifth Ave, New York NY

2pm Sunday 27 January 2008

$Museum admission

On Saturday the Vera List Center for Art and Politics at the New School presents Crafting Protest, a panel discussion on contemporary craft practice as a site of resistance and political agency. The panel moderator is art historian and critic Julia Bryan-Wilson, and panelists will include artists Sabrina Gschwandtner, Liz Collins, Cat Mazza, and Allison Smith. The panel is presented in conjunction with the Vera List Center's program on "Agency" and will address "the role of craft in forming national identities, especially in times of political turmoil or war; notions of patriotism; feminism and the domestic sphere; and economic models that circumvent conventional market models."

This Sunday, the Metropolitan Museum of Art will screen film works by Laurie Simmons and Sharon Lockhart, two contemporary American photographers. Simmons, known for her introspective, if slightly sentimental, portraits of dolls presents The Music of Regret, an original narrative work from 2006 in three acts, staring Meryl Streep along with a cast of ventriloquist dolls and several live performers. The film is comprised of three disjointed stories taking the form of radio play, an American musical narrative, and a staged "auditon" in which Simmon's signature giant objects with human legs dance wildly for off-screen viewers who judge the performance. Sharon Lockhart will present NO, a quiet, cinematic work from 2003 featuring two Japanese peasant farmers gathering hay and distributing it over a field. Lockhart's work takes on the character of still photography or landscape painting as its silent narrative unfolds over 34 minutes in the crisp 16mm cinematography; the title of the film suggests a link between the farmers' activity and NO-no Ikebana, a Japanese avant-garde flower arrangement practice. Both Lockhart and Simmons will speak with curator Douglas Eklund following the screening of their films.

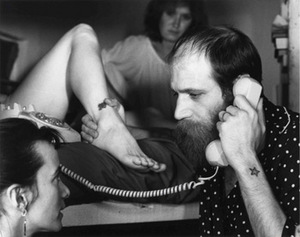

Guy Ben-Ner

5 January - 16 February 2008

Postmasters Gallery - 459 W. 19 St, New York NY

Some naysayers insist that contemporary conceptual art is nothing but illustration of political, philosophical, or ethical concepts already explored (more fully) by academics. The artists, they argue, are rightly excited by these ideas, but then doll up and dumb down the texts that inspired them in order to create something "new," and the commercial art world celebrates them for it. The Israeli artist Guy Ben-Ner, who has in the past decade produced some fine work, is typically exempt from such criticism, but Stealing Beauty, one of two Ben-Ner video works currently on display at Postmasters, is not.

Single channel video DVD, Courtesy Postmasters Gallery

Shot without permission in different IKEA stores near New York, Berlin, and Tel Aviv, "Stealing Beauty" follows the Ben-Ner family through a series of archetypal household routines: returning home from work, showering, surfing the Internet, washing dishes, preparing for bed. Ben-Ner gives these activities a sitcom treatment, right down to the happy, if vaguely maddening, musical jingle used for scene transitions and credits. Watching the family "live" in the IKEA showrooms is as funny as it is unsettling. Viewers will chuckle whenever IKEA shoppers wander into the shot, and some scenes — for example, a rubber-gloved Amir, Ben-Ner's young son, washes imaginary dishes in a kitchen showroom while a puzzled shopper looks on — are satisfying slapstick. Yet every shot is populated with bold IKEA price tags, hanging from the wall sconces, book shelves, lamps and chairs. When Guy and his wife, Nava, get into bed, we can’t ignore a framed photograph of a smiling blonde couple — not Guy and Nava — propped on the night stand. The point is clear: the Ben-Ners, like all of us today (to one degree or another), adopt a manufactured individuality and conform through consumption.

Hans Haacke at Paula Cooper

11 January – 17 February 2008

Paula Cooper Gallery – 534 W 21 St, New York NY

German artist Hans Haacke is known for taking uncompromisingly critical positions in high-profile exhibition sites around the world. In the 2000 Whitney Biennial, for instance, he exhibited Sanitation, a text-based installation of quotes from New York's former mayor and current Republican presidential hopeful Rudy Giuliani. In the piece, Haacke attacked Giuliani for his aggressive public maneuvering against the highly publicized Brooklyn Museum show Sensations of the previous year, which featured Chris Ofili's expressive rendition of a black Madonna adorned with bits of dried cow dung. In Haacke's installation, three quotes from the former mayor were reproduced as a wall-text in Fraktur Gothic, a typeface popular with the Third Reich, in front of a row of garbage cans out of which emitted the sounds of marching troops or an advancing army. The installation incited a kind of ruling-class furor from both the Giulianni camp and at least one of the Whitney heirs and namesakes of the museum – who rescinded her planned $1 million donation to the museum for that year and threatened to dissociate the family name from the institution.

It is not without trepidation that I evoke the Sanitation work of eight years ago; it would be nothing if not a mistake to misrepresent Haacke primarily as a creator of blunt, agitational artwork. His more recent public monument in Berlin to the revered German intellectual, writer, and committed socialist Rosa Luxemburg is, in contrast, a highly nuanced and sophisticated public work, on which Greg Sholette has written beautifully and with authority in Artforum's Novemeber 2006 issue. I begin with Haacke's work on Giuliani however because, with the former mayor's currency in the media spotlight, it is worth remembering his regressive brand of cultural politics, to speak nothing of his more fatal ideological standpoints. Haacke's tactics with Sanitation, in turn, match the hard-line rhetoric of the city mayor with the artist's own wildly provocation installation – and it works; when power got nasty, the art got equally nasty right back.

The consequent media attention on the artist was expected, and not something that Haacke was unfamiliar with by 2000, as his career is studded with such incidents. His partial destruction of the German pavilion in the 45th Venice Biennale in 1993, for example, incited similar uproar when it evoked the Biennale's history in Italy's fascist years and won the artist the prestigious Golden Lion award. This type of work however has perhaps made Haacke more enemies than friends in the international exhibition circuits, and, in some cases, resulted in hindrances to his exhibition potential. The 1971 work Sol Goldman and Alex DiLorenzo Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971 a photo-text installation documenting, in great detail, the property holdings of Manhattan's largest non-institutional land owning partnership, resulted in the cancelation of Haacke's solo Guggenheim show that same year and the firing of the Guggenheim's Edward F. Fry, the responsible curator who invited Haacke to present his work.

The press release for Haacke's current solo exhibition at Paula Cooper gallery states as much on the Sol Goldman and Alex DiLorenzo... piece, which is currently on display with four other works. The five pieces constituting this exhibition — each from from a discrete moment in the artist's career — together form a subtle and fiercely intelligent constellation of work.

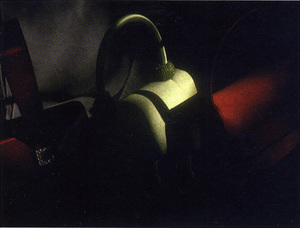

Courtest of Moved Pictures Archive via e-flux

Lawrence Weiner: The Complete Films and Videos

Anthology Film Archives – 32 Second Ave, New York NY

Various times, Wednesday 23 January – Tuesday 29 January

Beginning this Wednesday, the Whitney has partnered with the Anthology Film Archives to present an exhaustive Lawrence Weiner film and video retrospective, running parallel with AS FAR AS THE EYE CAN SEE, on view at the Whitney through 10 February. Weiner's engagement with both film and video since the 70s has produced a broad range and variety of work, reflecting the artist's continually novel approach to the medium in place of settling for a single style or working method. Weiner has produced short, conceptual video one-liners such as Broken Off (1970), in which we see five discreet scenes separated by dissolves in which the artist breaks or tears at various organic matter with his fingers, before finally pulling a live video wire that disrupts the tape; or Beached (1970), a short video shot in an outdoor location in which the artist again elects to do five simple acts in front of the camera. Weiner's practice later developed away from the ascetic rigor the these early black-and-white tapes into a more convivial working process, something that sets him apart from many producers of 1970s conceptual video. We often see sets in Weiner's videos populated be many colleagues and friends of the artists, playing roles or lending their voice to the soundtrack. Do You Believe in Water (1976), for instance, features a group of eight performers in a crowded scene talk to and try relating to one another in linguistic and physical exchange, a kind of improvisational theater driven by a language that resonates with Weiner's well-known wall texts. Done To (1974) consists of a simple still camera image of various figures sitting on a sofa while a dense soundtrack full of repetition and competing voices reminiscent of a William S. Burroughs cut-up experiment slowly develops. Weiner has also thus-far produced six feature length films, including the Nouvelle Vague inspired A First Quarter (1975) and A Second Quarter shot in mid-70s West Berlin.

Please see Anthology Film Archive's monthly schedule for show times. Alternatively, you can also access the information at e-flux, where a concise single page schedule is available.

Swirly Music

Brian Belott

CANADA - 55 Chrystie St, New York NY

29 November 2007 - 20 January 2008

"Go back to those gold sounds"

--Pavement

The 70s felt like the end of wanting, at least for a little while. Like a Carpenters' song, it was a lie, but it was nice while it lasted. Brian Belott's work touches on that gauzy itchy time. The era came burning through in the faded color of the found photographs I saw in a group show at Joymore in 2005. And now here it is again innocently (and sometimes not so innocently) consuming the space in his new show at CANADA, Swirly Music.

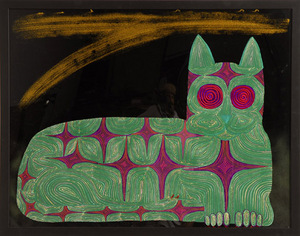

It should be said that I was more than a little worried when I saw the big, garish cats. Were they found paintings with some masterful glittery strokes applied by the artist? Across the room from the paitnings rest two Twin Tower like structures: dual, ostensibly random stacks of old hardcover books each support a television set on top, which in turn support a digital picture frame, the old media supporting the new(ish) and the new. These are the skeleton keys to Swirly Music. The two sets constantly play a stream of network IDs and TV movie intros that set the mood for the show, while the digital frames rotate through a series of Belott's found photographs — rhythmic and slow compared to the blown out colors and emphatic montage of the TV Land. The photos cover the spectrum from the odd rec room snapshot to a lost nudie of your neighbor's wife.

CANADA's big space is lined with colored clothespins and keys. The clothespins look like a continuous keyboard, while the keys made me think of Stevie Wonder's Songs in the Key of Life. That and the contents of a bowl at the door of a key party. The paintings in the room are exuberant homages to groovy posters and caricature. They initially looked like something done by an excited kid in a high school art class, and yet there is an emotional center that kept pulling me back in. The different pieces in the room worked their collective charms on me, and made me, well, a little swirly. That feeling was augmented by the soft soothing sounds coming from the bank of gold-painted speakers on the wall. It was light mood music that was as dedicated and focused as the show. Perfect.

I'm not sure why Belott keeps returning to the "gold sounds" of memory, but I'm always thrilled that he does. Art this specific in its mood is nothing short of a miracle. Don't be fooled by the fact that you can buy pieces of Swirly Music to take home. This show is one big landscape of memory. The paint, glass, fur, clothespins, keys, and TVs are just the colors and hues Belott busts out to show you what he's seeing from behind the canvas. And what he sees is beautiful, wistful, and a little goofy. A rec room long gone, all played out. Only the memories and the soft strains of a distant music remain. Ray Coniff and Henry Mancini would be proud.

CRG Open Video Series: DECAMERON

CRG Gallery – 535 W 22 St, New York NY

8pm 17 January 2008

The CRG Gallery's Open Video Series screening continues tonight with Decameron, curated by sculptor and video maker Yasue Maetake. Taking into consideration the eponymous 14th century Italian text to which the show's title refers, one might expect a screening of fragmented, pastiche narratives, and the press release seems to promise as much. The program features video artist Ronnie Bass, who exhibited a memorable narrative video in the 2006 Columbia MFA show on the longings and utopian ambitions of two computer store clerks and their manager, an interesting if spare representation of an alienated info-industry workforce, existentially confused and locked into a symbolic universe of cultish fantasy. Momoyo Torimitsu meanwhile often depicts modern desperation of a similar banality in her work. The artist is widely known for her realist kinetic sculptures of salarymen in business suits that crawl along the floor; her videos in the past have documented the robots crawling along public streets and busy urban centers. Tyler Coburn constructs short, digital video collages dense with figures populating utterly artificial landscapes. Peter Garfeld is known for his haunting photographs of crumbling, modest American houses falling from the sky and more recently completed his ambitious video debut: Deep Space 1, a three-channel triptych that shifts between views onto constructed sets, empty landscapes, and busy inferiors crowded with actors.

"This is hilarious" I told artist Dan Levenson, pulling out a thong ornamented with the floral Little Switzerland gallery logo. The sale of t-shirts not to mention exhibition branded lingerie falls considerably short of common within fine art circles, though so do corporate identities with no tax id numbers, bank accounts or regular hours of operation. Without knowing Little Switzerland's background as a conceptual art project about the branding and marketing of art, it might be just as easily confused for a front of some nefarious business enterprise.

Those familiar with the artist's activist efforts during MoMA's grand reopening however, would not make this mistake. Protesting the museum's raise in admission price from 12 dollars to 20 in 2004, Levenson's FreeMoMA.org campaign consisted of a wearable human sized currency, extended protests outside the museum, and informational fliers describing the problem. Since the high profile days of FreeMoMA, Levenson has continued creating work that addresses similar ideas, while maintaining lighthearted approach. "I have an interest in all the ways art work is disseminated that is extraneous from the object" Levenson explained, "the marketing, the advertising, the word of mouth, the hype… and just the business of the art gallery is fascinating to me and a lot of what Little Switzerland is about."

ArtCal Zine: And I imagine your position as an art maker gives you an important and unique perspective…

Dan Levenson: As an artist I am trying to co-opt that business and make it part of my artwork. So I'm interested in the postcards that galleries send out, I'm interested in the catalogs that they print, the essays that are in those catalogs. I love art gallery logos, I love art gallery letterhead, I love printed art gallery advertisements.

AZ: Speaking to this, can you talk about how you feel Little Switzerland identifies itself as an emerging artist gallery?

DL: Well, it’s flexible in terms of the forms it could take, but the story that I have now is that it is a gallery that began in Zürich in 1996 and then moved to Berlin in 1997 where it ran through three seasons and then closed in 1999. So it was an emerging artist gallery that represented a group of emerging Swiss artists. They were all young, they all knew each other, they all went to the same art school and they were all sort of “true believers” in my mind.

AZ: What are true believers?

DL: That’s something that I have a hard time explaining but I guess I divide artists along a spectrum of iconoclasts and true believers, and Little Switzerland is a gallery more for true believers than for iconoclasts. It’s an emerging gallery, so it was a little bit too loud and a little bit too promotional, the way that emerging artist galleries tend to be. We’ve spoken before about Bellwether and how their early graphic identity was a little bit louder and kitschy-er.

AZ: Yeah, their website was an illustrated storefront with someone walking in…

DL: Yea, that’s right! Which I thought was very very cool. And I loved that when they moved to Chelsea they had that pink neon sign that had their logo, which was Bickham Script, a very florid, 17th century-esque font. And of course they’ve toned it down now…I think they are aspiring to something a little bit more respectable and upscale and more Chelsea than Williamsburg. So Little Switzerland is more downtown and they have this kind of loud downtown logo, and then they print t-shirts and they have a kind of whole promotional merchandising aspect that I’m not aware that any real gallery has ever done. I don’t think that galleries generally sell t-shirts and coffee mugs and beer steins and stickers and that kind of stuff, but Little Switzerland does. And more than that, they sort of force their artists in the compromising position of having to model the clothing. So these are the artists modeling.

Artist and writer Deborah Fisher's new publishing project, SELLOUT, launched earlier last week. The blog features an eclectic series of posts on the practical side of economic survival as a fine artist in an often corrosively unsympathetic art world. SELLOUT is comprised on Fisher's musings on everything from juried review applications to professional community building. Often peppered, like her writing on Art Cal and elsewhere, with Fisher's wry humor, the new blog becomes as much an individual narrative as a kind of artist's personal finance blog.

Liz Kotz and Lawrence Weiner on AS FAR AS THE EYE CAN SEE

7pm 17 January 2008

Whitney Museum of American Art - 945 Madison Ave, New York NY

$8

In his popular 2002 text Dispersion, Seth Price suggests that "conceptual" has become a term with a sort of viral currency in contemporary art. Intellectually invested work across mediums is eagerly prefixed with this designation by artists to suggest a transcendent quality from the generally pejorative connotations of craft. Indeed such anxiety over art making in a post-industrial society, especially in terms of what is still made by hand (and why), might be attributed to any of several factors. Perhaps it is a symptom of the further entrenchment of contemporary art as a socially privileged cultural distribution channel; an art in which barriers of admittance are constantly renegotiated in the twilight of popular entertainment and media spectacles. Or, perhaps, what Price calls "today's normative Conceptualism" is the result of the regimentation of art education and an apprehensive desire on the part of practioners to identify with historically bracketed moments in the Western art of the past fifty years. The original concerns of American conceptual art were of course much narrower in scope than to what the word's current popularity attests. Linguistics, analytic philosophy, dematerialization, and a systemic approach to art making may lie at the core practice of many of the original group of American conceptual artists, of which Lawrence Weiner, the current subject of a 40 year retrospective at the Whitney, is a key member — and who remains a very active presence in New York. Weiner's other recent exhibition sites have gone from the way-off-center Project Utopia space in Bushwick, Brooklyn (reviewed here some time ago) to the just closed project space at Marian Goodman where Weiner had installed a single text spanning 3 of the gallery's walls.

This Thursday Weiner talks to scholar Liz Kotz about his Whitney retrospective, which is installed through 10 February. Kotz is the author of Words to Be Looked At: Language in 1960s Art, recently published by the MIT Press, a cross-disciplinary survey of the vanguard practices in visual art, poetry, and music of 60s New York and has rightly garnered the author some very favorable reviews.

Tino Sehgal

Marian Goodman - 24 W. 57 St, New York NY

30 November 2007 - 10 January 2008

Each visitor to This situation, the recently closed Tino Sehgal show at Marian Goodman, is greeted by a chorus of performers who chant, "Welcome to this situation," before walking backwards and assuming a tableau. One of the performers than recites a quotation and a discussion ensues. This process is repeated for each new arrival.The quotations are framed with two variables; the date and the author, who is either 'somebody,' or 'a Situationist.' Thus:

"In 1953 a Situationist said "The struggle against poverty has overshot its ultimate goal – the liberation of man from material care – and become an obsessive image hanging over the present. Presented

with the alternative of love or a garbage disposal unit, young people of all countries have chosen the garbage disposal unit."

or

"In 2005, somebody said, "The big question of our times is that… everybody… has to produce an income, in order to buy food and housing. But actually there is (little) which is really necessary - except what, say, 5 % of the population are producing in terms of housing and food. If the rest of production is unnecessary as well as problematic… How can I turn this equation, i.e. just produce something that is somehow also nothing and make an income out of it… Today we have enough material products… they are becoming counterproductive, but we still need to produce things because we need an income. So what else could we produce? And are these things then interesting? I think the experimental side of my work is that I produce things which fulfill certain criteria, for example the criteria of being sustainable. But then the question is are they attractive or are they just boring?"

and

On the Legacy of Colin De Land

7pm 11 January 2008

Orchard Gallery - 47 Orchard St, New York NY

This Friday Orchard hosts a round table on the late Colin De Land, the radical New York art dealer know since the 80s for his founding of vanguard exhibition spaces in the East Village and SoHo, support for oppositional and anti-commercial projects and actions, and camaraderie with several generations of important New York artists. De Land, founder of American Fine Arts and the Gramercy International Art Fair (antecedent of the Armory show), passed away from cancer in early 2003. The panel tomorrow at Orchard will be moderated by art historian James Meyer and will include contributions by Carol Greene of Greene Naftali, artist John Miller, collectors Barbara and Howard Morse, and artist Christian Phillip Müller, among others.

Carl Ostendarp, 1987 - 2007

Elizabeth Dee Gallery - 545 W. 20 St, New York NY

1 December 2007 - 12 January 2007

I walked into Elizabeth Dee transfixed not only by the works hanging on the walls, but the transformation of the space itself. With the top edges of the walls oozing pastel-hued candy pink paint drips I was transported back to a limited recollection of the pre-school phenomena — mud pies in the backyard, cooking apple sauce for the first time, little boys running to the bathroom with pants down, leaking all the way onto milk-vomit covered floors.

Childhood is all about an inundation of bodily fluids, and as we grow older we attempt to immerse ourselves in forgetting about them, or perhaps more or less acknowledge they're there, but not letting them dominate our memories.

In Carl Ostendarp's work, the artist quietly references the body's makeup and its processes through pop culture abstraction; body-like fluids take on a cartoonish quality with the flatness of his paint application. This retrospective of the artist's work currently on display offers a unique look at the his development in this regard since the late 80s.

MEDIUM COOL: Art in General's 10th Annual Video Marathon

Organized by Hanne Mugaas

79 Walker St, New York NY

Regarding Jeff's People

A talk by Ed Halter

6:30pm, 10 January 2008

Transition Objects

Curated by Thomas Beard

10 January - 12 January 2008

Artist Looking at Camera

Curated by Hanne Mugaas and Fabienne Stephan

10 January - 12 January 2008

Art Since 1960 (According to the Internet)

A project curated by Hanne Mugaas and Cory Arcangel,

performed by Cory Arcangel

6pm 12 January 2008

Flipped Chips

A screening and lecture by LoVid

7pm 12 January

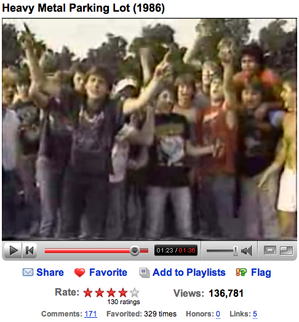

As part of Art in General's annual Video Marathon, organized this year by curator Hanne Mugaas, writer and media critic Ed Halter presents a talk this Thursday on Jeff Krulik, author of 80s cult video documentary Heavy Metal Parking Lot and several dozen other videos on the fringes of pop culture. Halter will use Krulik as a point of departure in a discussion that the press release promises to touch upon "the utopian hopes and mundane realities of public access television, the question of fandom and subjectivity, underground VHS bootlegging as proto-file-sharing, criticism of art and comedy, and the challenge of defining the term 'artist', and in particular, 'video artist'." The final point is especially interesting in the contemporary climate of media production moving from the world of art practice to social practice, the unregulated proliferation of webcams, and the amnestic resurgence of dot-com capital aspiring to the fever pitch of the late 90s backing it all.

Also opening on 10 January at Art in General are two concurrent video exhibitions: Transitional Objects curated by Thomas Beard examines some the medium's shifting roles in art and society, and Artist Looking at Camera curated by Hanne Mugaas and Fabienne Stephan, "highlights artists who use the tools of re-enactment, appropriation and moving image manipulation to question how history is produced and how facts are modified and reinforced through distribution." Later this weekend Cory Arcangel performs Art Since 1960 (According to the Internet), a talk and performance he first presented early last year at The Office of Contemporary Art Norway, New York, in which Arcangel, then partnering with curator Hanne Mugaas, faux-naively surfed the web looking for representations and reproductions of a weighty cast of mostly conceptual artists. One imagines the talk has been updated in the intervening months, so it will worth a visit even if you saw it at the OCA. Also on Saturday, glitch video artists LoVid present Flipped Chips, a show the duo has curated examining presented alongside a lecture examining various forms of tactile video practice and the artists who tinker with or construct their own video hardware, from Dan Sandine and Steina and Woody Vasulka to more contemporary practitioners like Paul Slowcum and noteNdo.

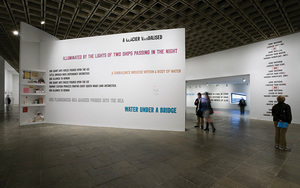

installation. Courtesy of the New Museum.

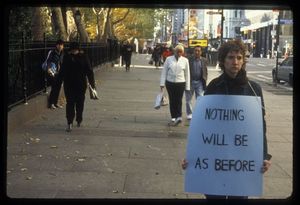

Sharon Hayes: “An Evening of Images and Ideas”

New Museum - 235 Bowery, New York NY

7pm, 10 January 2008

$Museum Admission (12)

This Thursday artist Sharon Hayes presents an evening of "images and ideas" at the New Museum to parallel her performance and exhibition of I march in the parade of liberty, but as long as I love you I'm not free. The title of the piece is a borrowed Bob Dylan lyric and a fine example of Hayes's practice. In her performances and media works, Hayes often dislodges historical speech and text from inert archives or collective social memory to bring them back into temporary and emphasized circulation. The humanity of these works, something that is immediately apparent when seeing Hayes perform, prevents them from becoming anything that is overly dry or formally stiff. Hayes seems to pour herself into her art, and isn't afraid to step outside of the gallery or museum, that safe place where art spectatorship and practice is constituted and reinforced. In September 2007, for instance, the artist performed Everything Else Has Failed! Don't You Think It's Time For Love?, a public week-long lunch-hour series of readings from a set of anonymous love letters on the corner of a busy midtown block. Performing in office slacks and a tucked blue sweater, Hayes seems as if she could have been any one of the many office-bound people who stopped to observe her, as she spoke with a hushed intensity into a single microphone and amplifier. Hayes here brought a private discourse into the a public space, as if it was a conversation collectively overheard, explicit in its intimacy but opaque in its context and the identity of the speaker(s).

Hayes has been performing I March... throughout the month of December, and one performance on 12 January remains. See New Museum website for details.

installation view. Courtesy of Wallspace Gallery.

From a Distance

Curated by Vincent Honoré

Wallspace Gallery - 619 W. 27th St., New York NY

29 November 2007 - 5 January 2008

Tomorrow is the last day to see From A Distance, an interesting if uneven group show curated by Vincent Honoré at Wallspace. The work in the exhibition ranges from very crafty assemblage and small sculpture to a few larger and more austere abstract works. Which category plays a stronger role here is hard to determine, but the small scale of most of the work on display makes the show a somewhat refreshing anomaly in Chelsea. A recycling of once vanguard 20th century forms and methods pervades the entire exhibition. Benoît Maire, for instance, contributes a series of seven black and white collages, pleasing to look at hanging in their irregular formation but a little too similar, to uncertain ends, to so much early continental surrealist collage. Roman Ondák meanwhile presents ten drawings of himself executed by anonymous people who received oral descriptions from the show's curator. Because the results are so radically disparate in style and execution — reflecting perhaps the lack of uniformity in arts training for most nonprofessionals — together they become unmistakably whole. Alban Hajdinaj's serial pastel portraits of Colonel Sanders on found KFC paper bags makes a gesture to the shared ambitions and techniques of pop art, branding, and fast food — although the final product is essentially only one of those things. The finished wood exterior to Nina Jan Beier and Marie Jan Lund's small box sculpture briefly belie that its constituting elements are a set of glued stereo speakers which emit a muffled tune, suggesting that even the most abstruse modernist art of the last century is vulnerable to repurposing in the anything-goes contemporary milieu.

Walead Beshty, one of the only two Americans in the show, contributes two of the largest works. Fold (Directional light sources...) is one in a series of abstract, camera-less photographs produced by a folding of photographic paper before exposure. The results are evocative of a Man Ray type of experimental procedure but, rather than novel in approach or zeal for new imaging technology, the work seems to point overwhelmingly at a tactile dimension in image making that is increasingly threatened by the sterility of digitization in the indexical arts. Fedex® Large Boxes, Priority Overnight, Los Angeles-New York meanwhile might be the strongest work on display. Consisting of heavy glass sculptures mailed snugly without padding in standard-size Fedex boxes, the work exhibited is only a trace of the process of package delivery usually abstracted in the commercial and business world. The movement of commodities is here rendered explicit and material: we see in beautiful detail the telling cracks and fissures in the once pristine glass upon which the commercial processes of corporate uniformity and contemporary business practice inadvertently inscribe themselves.

Enrichment

Nina Katchadourian

Sara Metzer Gallery - 525-531 W. 25 St, New York NY

17 November - 22 December 2007

The Hyena and Other Men

Pieter Hugo

Yossi Milo Gallery - 525 W. 25 St, New York NY

29 November 2007 - 12 January 2008

In the summer of 1998, the prolific visual artist and musician Nina Katchadourian used red sewing thread to "repair" damaged spider webs on Porto, an island in the Finnish archipelago. She photographed these repairs immediately after making them, but discovered that the web tenants would overnight extricate her "patch jobs" and fix the web using their silk.

The "Mended Spiderweb" project is typical of Katchadourian's practice; wry humor and whimsy are integral, but an exuberant sense of wonder impels the work. The three works in "Enrichment," Katchadourian's current solo exhibition at Sara Meltzer Gallery, continue in this mode, though they also contemplate a somber side of humanity's relationship with the rest of the animal kingdom.

In Meltzer's upstairs gallery, Katchadourian has arranged wallet-sized pictures of animal species in a linear spectrum that transitions from incredibly cute, at the center, to "uncute," at either extreme. Initially, I thought "Continuum of Cute" worth only a chuckle, but as I reviewed Katchadourian's placement of the various species, I wised to the work's sly reproach. The "cute" animals are most often mammals with large, liquid eyes, those that conservation non-profits choose as their emblems, animation studios turn into cartoon protagonists, and children beg their parents to acquire as house pets. In this respect, Katchadourian's "Continuum of Cute" is not unlike a beauty pageant, but one in which the participants are not being judged by their own kind. The exhibition press release points out that "the entire spectrum is reconfigurable...and therefore hints at the subjective hand that each viewer would bring to" the task but, lest we forget, each of those hands is human.

Nearby, Katchadourian has arranged six televisions in a circle around an exposed, vertical pipe, each screen facing outward. When I ascended the gallery stairs, the two screens facing me were black. After several moments, however, the screen on the right lit up. I watched as an orangutan methodically crossed two suspended cables, moving from right to left. As the ape moved off the left edge of the frame, the next television screen was triggered and, on it, the same clip began anew. After the orangutan passed across the second monitor, he appeared on the third, and so on. Round and round the orangutan goes.

Three Shorts by Nathaniel Dorsky

8:15pm Thursday 3 December and 5pm Saturday 5 December 2008

MoMA - 11 West 53 Street, New York NY

$10

For the length of his time as a filmmaker, Nathaniel Dorsky has worked towards an ideal of an open cinematic form, as close to 20th century American poetry as to the lyrical abstractions of American avant-garde cinema. What Dorsky has for years theorized as a "polyvalent" cinema is one in which the language of film communicates without acquiescence to narrative or thematic structures, or the ascetic formalism of 70s minimal film. The majority of Dorsky's films are thus composed of an assemblage of photographed fragments from the filmmaker's life, sometimes collected over many years. The results are nothing if not beautiful, filled with a kind of exuberant impulse to relate what Dorksky has described as "stanzas" of documentary motion picture photography in a deeply sensual way. One could well criticize Dorsky for making art that is too beautiful. In Devotional Cinema, a short manifesto of sorts published in 2003, Dorsky describes cinema as a potentially holistic, quasi-spiritual experience and likens the projected image on the screen to to the subjective experience of "our own skull like a dark theater, and the world... in front of us in a sense a screen." This metaphor may sound familiar to the adherents of film art, though in Dorksky's case, watching his lush silent 16mm films, one gets the sense that his own devotion to his art truly is religious.

Each of Dorsky's films is directed by its own internal sense of rhythm and every discrete frame's relation to the next; this is what polyvalent editing is about. His most prominent colleague in this regard, and one most likely to have an influence outside of the sometimes esoteric field of avant-garde cinema, is Stan Brakhage, whose tremendous output of oftentimes abstract and lyrical films has gained great currency in recent years even outside of art-film circles. Brakhage was, and Dorsky still is, a film purist of course, in spite of stratospheric production costs and the utopian distribution alternatives offered by video. Dorsky distributes his films in rentable, unlimited editions through San Francisco's Canyon Cinema, a long-time fulcrum of the West coast avant-garde film scene. Compared to an artist like 2006 Hugo Boss Prize winner Tacita Dean though, who also makes very medium-specific lyrical films, Dorsky is less interested in turning his medium into a precious object or mourning the slow decline of film technology — as if an international art cadre could alone stave off the processes of planned technological obsolescence, or, likewise, should symbolically declare the exhausted technology dead and buried. His films, rather, vacillate between deeply personal and ambitiously grand in their scope. Dorsky has made formal works about film grain and light, about the places he has lived and his colleagues and acquaintances, as well as grander gestures towards the function and possibilities of light and vision itself. The three films showing at MoMA were described by P. Adams Sitney in November's Artforum as a sort of devotional triad: Song and Solitude is a tribute to the filmmaker's dying friend, poet Susan Vigil, whose only appearance in the film is a brief close-up of her hand as she reads a T.S. Eliot's Ash Wednesday; Threnody is an "offering" to Stan Brakhage, while The Visitation is elliptically about the emergence of light and its sweep across the world.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian