This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

Recently by Adda Birnir

Shimon Okshteyn

Heist Gallery - Shimon Okshteyn at Heist, New York NY

10 October - 7 November 2008

For one more week, merry wanderers and afternoon flâneurs can find a funhouse gallery of mirrors hidden on a quiet block of Chinatown. Tucked between two small shops on Essex Street south of Delancey, you can enter a wormhole that will send you back to a Coney Island spectacle or a Times Square peep show. But peek around the corner of a mirror and you will see nary an amusement ride technician nor a beautiful girl, but a cheerful gallery attendant eager to hand you a press release.

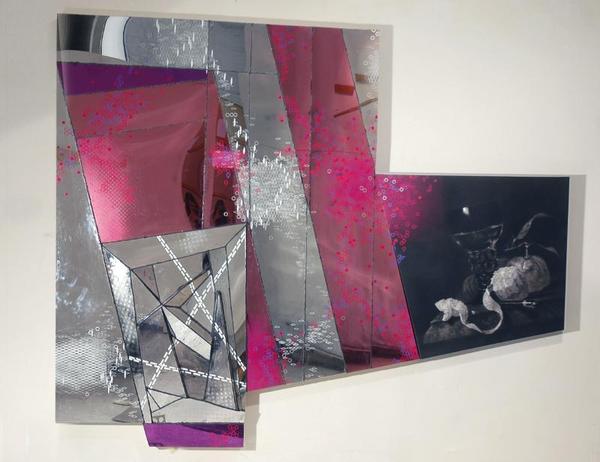

Shimon Okshteyn's show, Reflection on Reality, is the fourth exhibition at the newly opened Heist Gallery located in eastern Chinatown. The immersive installation, including a mirrored floor, is made up of slightly distorted mirrors bolted to the gallery walls. The mirrors swell and contract light and splinter where the screws bite. Thin purple and pink neon bulbs light the hall, bouncing against the opposing mirrors, and illuminating the space with an appropriately artificial glow.

The focal piece of the exhibition is a voluminous protrusion of glass that juts out of the left gallery wall. Composed of broken glass sutured together to form a small peak, the horizontal mountain is surrounded by painted canvas, and decorated with a graphic lace-like pattern. The rupture is wonderfully frightening, a 3-D realization of the sinister curiosity that leads us to the hedonistic spaces of amusement parks and red light districts.

Okshteyn does undermine some of this darkness with what looks like a computer-generated decorative overlay. But what he takes away, he gives back in a small painting titled Julie, an image of a woman post-coital. On its own the work is charmingly rough, endearing in its earnest simplicity. Coupled with Boy Smoking, a slightly larger painting of a boy doing just that, and placed in this seedy and otherwise reflective context, the works charm while making sure gallery goers catch the sexual undertone.

The strength of Okshteyn's exhibition comes not from the material installation or individual works here on display, but rather from the totality of the exhibition as both environment and an unlikely observation deck for the surrounding neighborhood. The most interesting vantage point is at the far back of the narrow gallery space, looking out. Standing against the back wall, the glittery mirrors frame a captivating view of the life of the Lower East Side breathing and moving outside the gallery window.

Only a handful of blocks south of the glossy bars, nightclubs, and organic markets that now suffocate the once Caribbean and Italian arteries of the Lower East Side, Essex Street between Hester and Grand remains a relatively unblemished stretch of Chinatown. Across the street, past the slightly beat up Toyota and Ford sedans, is a modest basketball court presided over by the forlorn towers of Cooperative Village. Although Heist Gallery is one of the several cultural enterprises that dot the neighborhood map, for the length of Okshteyn's show they provide something unique: a remarkable opportunity to sit and appreciate the comforting banality of everyday life that still has a place in this small corner of lower Manhattan.

Ryan McGinley

I Know Where the Summer Goes

Ryan McGinley

3 April - 3 May 2008

Team Gallery - 83 Grand Street, New York NY

New York based photographer Ryan McGinley made a surprising admission in the press release for his latest show, I Know Where the Summer Goes: his photographs are staged. In fact, the lithe young things writhing in the 30 or so pictures on display at Team Gallery are models that he cast in an official casting call where each potential model was judged on "mellowness... strong personalities," comfort naked and "long-limbed[ness]." And then the road-trip across the country was meticulously planned, with locations extensively researched for their symbolic weight and McGinley planning plenty of activities for his hired cadre of enthusiastic companions to partake in. The truth is that McGinley’s images have always been staged in his drive to create an aesthetic world where youth runs wild against the backdrop of iconic landscapes of the American West, this is just the first time he admitted it on paper.

This explicit admission forces the photographs to stand on their own, without playing on the audience’s fantasies about the spontaneity of their creation. In previous bodies of work, McGinley’s photographs have largely ridden on their off-the-cuff sex appeal: the images have captivated viewers with their patina of sex, drugs and rock n’ roll, without any of the harsh, gritty, uncomfortable realism of documentary photographers Larry Clark or Nan Goldin. In the former photographic world of Ryan McGinley, youthful exuberance trumped all as adolescents playfully wrestled, jumped, frolicked, fed horses, and unselfconsciously fucked in shower stalls.Women in Experimental Film

Co-presented by The Film-makers’s Cooperative and PS1

2pm Saturday 1 March 2008

PS1 - 22-25 Jackson Ave, Long Island City NY

Women Behind the Lens, Panel Discussion

Presented by CineKink

Moderated by Rachel Kramer Bussel

5pm Saturday 1 March 2008

Anthology Film Archives, New York, NY

1965, color film in 16mm, 22:00 minutes

Running concurrent to the WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution exhibition at PS1 and boasting its own set of events, was the less high profile CineKink Film Festival. The festival, whose aim is to continue "the recognition and encouragement of sex-positive and kink-friendly depictions in film and television" — according to the letter of introduction written by CineKink Co-Founder and Director Lisa Vandever — focuses primarily on porn, a topic deplored by many feminists, yet one that resonates deeply with much of the work on display at PS1.

Saturday March 1, 2008, in a moment of programmatic convergence, PS1 in Long Island City screened the works of seven experimental feminist filmmakers followed by a panel discussion; across the river at the Anthology Film Archives, CineKink hosted its pornographic version of the same event, showcasing woman-directed works of pornography followed by a panel discussion with the filmmakers.

The Women in Experimental Film screening at PS1 featured films made by feminist filmmakers Barbara Rubin, Marie Menken, Carolee Schneemann, Barbara Hammer, Marjorie Keller, Peggy Ahwesh and Abigail Child. Of the seven films screened, three films dealt with sexuality and sexual encounters explicitly, and a fourth one focused entirely on the mechanisms of the body.

Barbara Rubin’s Christmas on Earth involved a simultaneous double projection, one larger and the other half its size, superimposed on top of one another. According to an essay by Daniel Belasco published by Art in America, the 29-minute film is the "record of an orgy staged in a New York City apartment in 1963." The larger image consisted primarily of images of female and male genitals, and close up shots of couples making love. The smaller projection showed the participants' entire bodies. Rubin imbued both projections in hues of deep red and purple paint. When creating The Color of Love and Covert Action Is This What You Were Born For? artists Peggy Ahwesh and Abigail Child, respectively, spliced together found footage that consisted of both professional and amateur pornography. In both films, the heavy editing and deterioration of the film upsets the narrative, such that images become surreal and disconnected and cease to read as traditional pornography.

Courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery.

Kohei Yoshiyuki

Yossi Milo Gallery - 525 West 25th Street New York, NY

6 September - 20 October, 2007

If you have read anything about Kohei Yoshiyuki’s show The Park, currently on view at Yossi Milo Gallery, you know the basic story — that Yoshiyuki went about photographing young lovers coupling in Toyko’s public parks and the many men who watched them do it. As told to The New York Times columnist Philip Gefter, the story goes that one night in the early 1970’s while innocently photographing lit skyscrapers, Yoshiyuki strolled through a local park and happened upon a group of men secretly watching a couple fool around. The couple seemed unaware of the rapt audience and went about their business unperturbed. Intrigued, Yoshiyuki decided to shift the focus of his camera lens away from the steel phallus to real phallus. After spending months infiltrating and observing these clandestine gatherings sans camera, Yoskiyuki began documenting the events without disrupting the lovers or the peeping toms, using a film camera outfitted with an infrared flash.

The Park series captures two of photography’s most salient characteristics: photography is both a documentary and voyeuristic medium. The original presentation of The Park focused more attention on its voyeuristic aspect than does the show at Yossi Milo. When Yoshiyuki showed the work in 1980 he printed the photographs wall sized, turned off the lights in the gallery, and equipped gallery goers with flashlights to view the images in order to replicate the experience of being in the park — he was quoted in The Times saying that he wanted viewers to have to look at the bodies “inch by inch.” For this show he printed the images at a modest 16 x 20 inches and displayed them documentary style, in a neat line, one abutting the other. Though this show is less salacious than its predecessor, the original presentation was more honest about the audience’s relationship to the photographs. The act of looking at these photographs is voyeuristic. We should revel in that, not pretend as if we can maintain a cool distance.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian