This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

May 2009

Technology usually plays a central role in narratives of progress. Broadly understood as sedimented human ingenuity, different stories grant technology a greater or lesser role in our eventual emancipation. Some even see technology as alienating or ensnaring us - preventing us from an ill-defined happiness. What is less clear, I think, is where we draw the line designating technology. Take something like the bill of rights. It has certainly progressed since the original ten amendments, but we would not call it technology. Perhaps a better example is something like conceptual art. To what extent does this form of art - more complex and difficult, and yet more popular and diffuse than that which came before it - represent something like the arrival of a new or the improvement of an old technology? Similar questions could be asked of advances in problem solving skills, management techniques, or any number of non-electronic advancements.

There is also the more pragmatic side of the discussion, namely if, specifically network technology, is to link us together, how do we go about making sure that everyone has access to it? Ethan Zuckerman and Omar Wasow will discuss this and other questions at the New Museum tomorrow.

The figurative rendering of a cultural imaginary is not new terrain. A good deal of work consists simply in recording the exaggerations and misreadings ostensibly structuring our collective unconscious. At worst this tendency amounts to little more than vapid expressionism mistaking itself for critical sociology, an effect often exaggerated by an ongoing game of pin-the-identity-tail-on-the-ideological donkey. At first glance, Liao Yibai's Imaginary Enemy, seems a prime candidate to continue this unfortunate tendency. A series of sculptures "explor(ing) how (the) Chinese imagined the myth and threat of America during and immediately following the Cultural Revolution," Yibai could easily have repeated any number of well-worn narratives and nobody would have blamed him. He would merely have been repeating what is perhaps the signal error of this mini-genre, mistaking what is true for what is compelling and relying on brute force of polemic or moral clarity to do the work of the aesthetic object,

Yibai, by contrast, and to his great credit, hews very close to his own idiomatic experience of these cultural myths. He chooses for his studies those moments that reveal himself and his world in tandem, preventing a fall into wrote commentary. Thus PLA Whiskey, a massive, stainless steel Jim Beam bottle, with certain details spelled out and certain others reduced to squiggles, "recalls the story of a former Chinese soldier’s dream of forbidden American alcohol." Cash Fighting is a delightfully literal representation of the economic struggles between China and the US, and has Benjamin Franklin leaping out of a one-hundred dollar bill to box with his Chinese counterpart. Its a simple, comical gesture - but also a poignant one; realizing a childlike comprehension of conflict in the broadest of strokes. Less monumental but more effective is a series of aircraft carriers, repeated as a progress of somewhat amorphous polygons, each with its own series of smaller shapes on deck. Rendered in the same, shiny steel as all the pieces here, these ships capture the American presence in the South China Sea as a hard and inscrutable power, difficult to comprehend at the level of its individual parts and machinations. Its an altogether effective presentation. The show is open until August 15.

"I would like," wrote Michel de Certeau, "to follow out a few of these multiform, resistance, tricky and stubborn procedures that elude discipline without being outside the field in which it is exercised, and which should lead us to a theory of everyday practices, of lived space, of the disquieting familiarity of the city." And so he did, creating, in the process, one of the properly liberating texts in the theoretical canon; The Practice of Everyday Life. For de Certeau, the everyday life of the consumer was not simply fodder for Foucault's insidious disciplinary dispotifs, or the mere mechanized banality excoriated by the situationists, Vaneigem's "...desperate fraternity in sickness." Instead, it was the site where a marginalized majority deployed countless individual tactics to subvert, undo, repossess and otherwise reclaim an alienated landscape. To wit: "Imbricated within the strategies of modernity... the procedures of contemporary consumption appear to constitute a subtle art of 'renters' who know how to insinuate their countless differences into the dominant text."

What then to make of those contemporary artists who focus on the 'everyday' as the basis for their own practice? This will be the topic of a discussion this Thursday at the MOMA, featuring two artists ostensibly so involved, Tino Sehgal and Lee Mingwei. Sehgal, for one, has often been asked about the lineage between his work and the historically oppositional cast such dematerializations have aspired to, an affinity he seems to reject. Tickets are ten dollars, eight for members.

Collaboration in the visual arts today is not without its contested legacy. Some writers have characterized its manifestations among younger contemporary artists as a kind of collective self-branding, a retrofitting of collaboration's politically left or utilitarian origins (in the United States, certainly) to a sort of modish rock and roll production model. Others meanwhile have described artistic collaboration in the more polyvalent terms of a dispelling of the authorial heteronomy often resulting in an art system which calls for individual artist brands and highly deliberate career arcs. Curators, like artists, frequently collaborate on their own terms. The pracitice has been by now normalized in some very high profile and important international exhibitions. There, divisions of labor, curatorial "sub-contracting," and topical specialization have become the norm. So while artists and curators thus often work together to realize projects both ambitious and everyday, the art critic, meanwhile, remains strangely alienated from this otherwise socially promiscuous milieu.

The critical voice has of course historically been distilled and distributed in publishing as the a collective editorial voice, and yet new models of collaboration remain to be found. An event tonight at the National Academy Museum seems likely to formally speak to this issue. There, at 6:45, David Cohen will assemble the thirty first manifestation of his Review Panel series, inviting four young writers to comment on the New Museum's recently inaugurated generational triennial currently there on view.

Tomorrow meanwhile at Goethe's Institute's Wyoming Buidling, sound artist Carsten Nicolai will perform at 6pm, concluding the Institute's Reinventing Goethe project, a kind of collaborative and exposed reimagining of the event's host building. Of Nicolai's splintered affiliations one of the more noted is his co-founding of German electronic music label Raster Noton, which is next week opening a temporary botique at e-flux's New York location, the second in a series of exhibitions at the space.

Thursday, a panel moderated by Marek Bartelik and Barbara A. MacAdam, will consider the relationship between the national frame and art criticism. As art become increasingly international the task of interpreting and considering art works changes, as a great deal of a critical energy usually revolves around the appearance or instrumentalisation of different ideologies and structures of power. How do critics locate and interpret art across boundaries? Phong Bui, Eleanor Heartney,Kim Levin, Lilly Wei, Linda Yablonsky, will discuss. The event is at the Museum of Arts and Design at 6:30, reservations are recommend as seating is limited.

It is perhaps telling, if not yet wildly significant, that Ranciere begins his essay, ‘The Future of the Image,’ by analyzing the opening of Bresson’s Au hasard Balthazar, and does so in contrast, furthermore, to a French game show. The comparison is between two images, plain and simple; marking our arrival at the moment when what formerly required qualification as a movement-image, say, or a time-image, has become simply 'image.' Moving images, in short, have become the norm. At first glance this is merely a further example of the Rancierian move par excellance: the repositioning of the radical or the disruptive as definitive - thus all politics is radical politics, all art the ‘redistribution of the sensible,’ and so on. Yet he proceeds to lay out an entire taxonomy of ‘image-ness,’ setting aside no special distinction for the moving image beyond, perhaps, implicitly setting the criteria by which all images are, henceforth, to be judged.

This splitting of the moving image into types, first from television, and then later from within cinema itself, recalls Deleuze’s desire to distinguish between the aforementioned time- and movement-images. Both philosophers wish to carve out, rescue even, from within moving images as such, something like the arrival of a redemptive, abstract, Modernist cinema; a cinema capable of a certain sort of resistance. And this effort stands in striking contrast to those many thinkers for whom cinema is capitulation itself; to mass culture, to passive spectator-ship, to an altogether impoverished form of representation, etc.

Thus the question – what is the horizon of the moving-image? What sort of modernity is permissible under its rule? Tuesday, Mauricio Dias, Walter Riedweg, Beatriz Jaguaribe, John Hanhardt, Gabriela Rangel, and Heike Arzápalo will discuss the relationship between moving images and discourses of the modern at the Americas Society. The panel begins at 6:30.

Blanks, Templates, Undos, Redos, Matt Sheridan Smith's debut solo exhibition at Lisa Cooley, is comprised of opaque sculptures and drawings which occupy a vague, transitional territory despite their resemblance to several ubiquitous forms in present day work-life.

The show's sole video, Untitled (open/shut), 2008 (all other works 2009) is a seven-minute montage cut from footage of actors opening and closing doors in Robert Bresson's film, L'Argent (1983). In Smith’s edit, the characters endlessly pass into and out of boutiques, cafés, homes, offices, and other spaces. Departing prompts removed, we’re given the momentary silence of a door swinging ajar, over and over again. Smith’s projection is a figural representation of his blanks, templates, undos, and redos; transitions that never lead anywhere but serve to personalize the concepts of banality operating within the other works on view.

A form in decline, the print magazine remains a pernicious breed. Contemporary fame is largely its doing; the fawning, uncritical portraiture, the endless parade of high gloss mediocrity. More topical than books, better looking and more permanent than newspapers, magazines exist in a certain dastardly harmony with capitalism. They are appropriate to it, somehow, as even those trade publications that avoid the worst excess' wield a disproportionate power. Over the next decade it will be our privilege to watch this form attempt a translation to the interwebs - a move some have already begun with varying degrees of success. What has eluded these attempts has been a proper online version of the old fashioned article, complete with an effective integration of text and image.

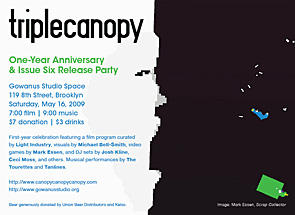

Not so with Triple Canopy, an online publication that, in addition to avoiding the worst features of its predecessors sketched above, has also created a genuinely pleasant and elegant interface. Using JavaScript, TC has been able to keep the good parts of print while avoiding the clumsiness of pdf-style navigation, and, after one full year of excellent content published in this manner, its having a well earned celebration. This Saturday at Gowanus Studio Space Triple Canopy celebrates its first anniversary, featuring a film program curated by Light Industry; visuals by Michael Bell-Smith; video games by Mark Essen; musical performances by The Tourettes and Tanlines; and DJ sets by Josh Kline, Ceci Moss, and others.

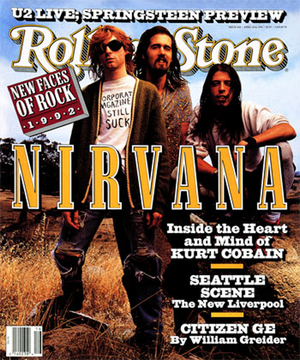

For a decade that is almost another full decade behind us, the nineties remain mercifully undefined. Generally prosperous, and remembered chiefly for the mass culture debut of so-called 'alternative' music, the nineties may actually be remembered as the last moment before the internet shattered pop culture into many tiny pieces. In a way the absurd title of 'alternative' betrays an uncomfortable straddling that foreshadows what was to come. Alternative to what exactly? What sort of thing was being designated here? Certainly the most obvious absence at work in the popular imaginary of the nineties is the end of the cold war. For an event so historically important, it still sometimes feel as though it has yet to register in the minds of many Americans. Perversely, 'alternative' can thus be read as a sort free floating gravestone, marking the death of the last genre worthy of the title, albeit many thousands of miles away.

On Friday, the New Museum convenes an impromptu summit to determine what exactly we are nostalgic for when we pine for the nineties. Speakers include Michael Azerrad, Mark Greif, Emily Gould, A.S. Hamrah, Marisa Meltzer, and Aaron Lake Smith, The panel starts at seven. You might consider getting tickets in advance.

Lionel Trilling, in the course of arguing that the focus of personal morality had shifted from a Victorian era emphasis on outward consistency, or sincerity to a proto-existential adjunct to 'be true to oneself,' known as authenticity, quotes Andre Gide's remark that, "One cannot both be sincere and seem so." Jane Taylor, who is speaking tommorow at the New School, seems to be making a similar point when she says, "Anywhere that ‘sincerity’ names itself, it ceases to exist. It is a value that is vouched for through a circuit of social consensus, in which it cannot itself trade." Its an interesting moment to bring back a discussion of the term, as sincerity, or its absence has become an essential feature of a certain mode of ambition. Further, it seems somewhat incongruous that someone could be both insincere and authentic, as the precisely the desire to be insincere, or the one which motivates insincerity reveals a corresponding lack of authenticity.

Recently, Taylor has examined the various historical and theoretical relationships between subjectivity and performativity. Juxtaposing sincerity with her work with visual artist William Kentridge, Taylor's lecture tomorrow will also touch on her work in South Africa with the Truth and Reconciliation committee.

Freedom and Beauty: The Art of Iraqi Refugees

St. Paul the Apostle - 405 W 59th St, New York NY

30 April - 28 May 2009

Everyone's talking about faith these days. In a recent issue of Commonweal, Terry Eagleton suggests that we ought to be attentive to the critical potentialities of religion; they are crucial, he thinks, because they provide an alternative to both radical fundamentalism and liberal-rationalist dogmatism. In a sense, it's easy to see what's at stake for him. Religion as a field of study now fills a niche once occupied by certain varieties of Marxism: it is, paradoxically, an ideologically uninvested space where adventurous approaches are welcomed rather than shunned. If its appropriations of Heidegger and Badiou are occasionally unrefined, it is because it's still something of a critical frontier.

The exhibition Freedom and Beauty: The Art of Iraqi Refugees, on view this month at St. Paul the Apostle Church, brings this frontier quality immediately to mind. Its engagement with theory, to be sure, is minimal. Nonetheless, the aggressive way in which it breaks with curatorial common sense is something of a statement in its own right. Paintings by four artists are arranged on a single display stand, crammed sardine-like into a few square feet. (Another artist is displayed on a slice of adjoining wall). The accompanying exposition in the press release and wall texts spends vanishingly little time on the paintings themselves. It focuses, rather, on the circumstances of their production, as even the title suggests. It describes the artists' experiences in war-torn Iraq and emigration, positioning the work itself as merely a response or an expression of the crisis — anything but l'art pour l'art.

But just as it makes little effort at any move towards something like contemporary exhibition practice, the exhibition also avoids making explicit political statements — it identifies neither culprits nor solutions — and, more strikingly, proselytizing. The objective seems to be the establishment of an interspace between traditionally ecclesiastical, artistic, and political sites and styles of dialogue. Though perhaps this is a grand claim for what is, after all, a fairly modest undertaking, its organizers are hardly strangers to such projects: the exhibition is the work of the Paulists, a missionary order that sees new media and cross-cultural exchange as fundamental to its evangelism. Freedom and Beauty, in short, represents a kind of religion even a Marxist like Eagleton can approve of. It is hard not to applaud the effort or appreciate its undermining of the borders between cultures and professions.

Too frequently the conversation surrounding gentrification amounts to a frustrating mix of polemics and general confusion. Rarely has an issue been opposed by more people less effectively. This is all the more interesting because the process usually has its roots in very simple zoning adjustments designed to attract the creative underclasses - typically the adjustment of industrial ordinances to allow for live/work spaces. Which is to say that the opposition should have a pretty clear and easy goal; namely stopping such changes from being enacted at the municipal level. And yet this is rarely the case as the issue comes to stand-in for fissures within the dominant classes - as artists oppose hipsters oppose the bridge and tunnel crowd and so forth.

This weekend marks the opening of the fourth installment of a refreshing take on the question, the HomeBase project, an annual, site-specific, artist-run investigation of the question of 'home.' This year's episode will take place on the Lower East Side. Bringing together artists working in many different media from all over the world, curator and founder Anat Litwin attempts to create a space that simultaneously investigates the surrounding neighborhood, as well as whatever concept of home the artists bring to the table. Though not explicitly an investigation of gentrification, the choice of neighborhoods, SoHo, Greenpoint, Harlem, and now the LES, shows a sensitivity to those neighborhoods most in-flux with regards the question of home.

The location for HomeBase 4 is the Bilaystoker Center for Nursing and Rehabilitation, at 232 East Broadway, This year's artists include David Bar Katz, Willum Geerts, Oded Hirsch, Sandra Lee, Pessi Margulies, J. Morrison, Abby Robinson, Paul Sepuya, Dafna Shalom, and Letha Wilson.

We often imagine the arrival of cinema as a clean break with the traditions of popular, live performance; as though (popular) film arrived as the ham-fisted alienation it is today. Yet for the many decades of domination by silent films, their soundtracks were performed live by in-house musicians. Perhaps inhabiting the same sort of quasi-creative space occupied today by DJ's, silent-film musicians found themselves fired by the thousands when The Jazz Singer premiered, which, in addition to contributing to the historic coincidence of cinematic turning points with gratuitous racism, also heralded the arrival of the talkie.

Recently however, there has been a resumed interest in silent film musicianship, though not quite of the kind available at Smack Mellon tonight. Inspired by the possibilities of a collaboration between contemporary musicians and silent films from a previous era, cuator Molly Surno has paired New York 'art punk power trio' Lycaon Pictus with Pitor Kamler's Chronopolis and Joel Schlemowitz's Bagatelle. Doors are at 7, show is at 8. Come early for a free beer tasting. Suggested donation is five dollars.

Michelle Lopez - The Violent Bear It Away

21 March - 17 May 2009 at Simon Preston Gallery

301 Broome Street

A conversation with artists Michelle Lopez and Andrew Cornell Robinson that took place in both of the artists’ studios in Bushwick, Brooklyn on 7 April 2009.

Andrew Cornell Robinson: When you went to California there was a shift in your work. In fact there seems to be several moments when your work has undergone significant shifts in attention and focus evidenced by the materials you use and your conceptual concerns.

Early on you started to work with leather, which became your signature material. Much of your work has had this intense exploration of material. What’s that about?

Michelle Lopez: Back in grad school, I was working with chocolate, and apple skins. I was trying to find a way to re-contextualize a material, something that was incredibly familiar to us. In a way the work is about how to invert something that is masculine and make it feminine, create this ambiguity. The thing that I am interested in most, is exploring androgyny. In terms of my education, I was interested in a feminist perspective, but I wasn’t really interested in a feminist aesthetic.

AR: What do you mean, like Judy Chicago?

ML: I was interested in feminist theory but not entirely convinced by the art, well yeah Judy Chicago, like all of the artists associated with early feminism.

ACR: A friend of mine calls that aesthetic “My Tortured Vagina” art.

ML: (Laughter) Exactly! So in a way I wanted to create work that was specifically non-gendered. For me it’s really hard to talk… I don’t want to be specific about the language. I feel like I can so easily get pinned down, and I don’t want to, so it’s better for me to keep the ideas open.

Are spaces and places of consumption actually laden with significance? Or are they simply the last shared experience we have left to talk about? (and is that all that makes them significant?) Despite being one of the most consistent tropes of our inherited critical landscape, it is sometimes hard to dinstinguish the gesture towards consumption - the passing or even sustained acknowledgment of its prominence is what passes for public life - from its critque. When the culture industry displays even the slightest hint of self-consciouness, by setting a zombie movie in a mall, say, everyone trips over each other proving what a cheap critical date they are; tittering on and on in an embarassing state of metaphoria.

The flip side is those rare occassions when certain brands actually do cross over from the background noise of advertising into something approaching cultural significance, a moment marked by their appearance in conversation alongside media personalities, tv shows, and anything else whose personal space they would typcially have to pay to share. IKEA is such a cross-over phenomenon, straddling the line between shopping and lived experience just a little more convincingly than its competitors. Its strangely cheap. Its tinged with a foregin exoticism. It has food. It is also, for a certain segment of the population, a nearly universal pilgramage. No doubt it is this rare appearence of somthing like universalism that Guy Ben-Ner targets in his video work, Stealing Beauty installing himself and his family in a series of IKEAs throughout the world, attempting to wring comedy from the juxtaposition of a real familiy in a fabricated place. Ben-Ner will discuss this, and other work, tommorow at the Guggenheim.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian