This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

July 2009

Saturday, August 8th, the Laundromat kicks off its 2009 season with The Burger Group Show – a one-day exhibition complete with selections from The Laundromat Flat File and a menu of 'conceptual burgers.' The show features work by returning Laundromat artists, as well as newcomers who will be exhibiting their work with the space this fall.

Each participating artist has crafted a 'conceptual hamburger' that references the study of art history, or art-related concepts. The artists will be writing descriptions of their respective burgers for the menu, and cooking their creations for patrons. Founder and director of the Laundromat, Kevin Andrew Curran, sees the menu as a "tongue-in-cheek" opportunity for the artists to make commentary and fuel artistic discourse.

Curran does not intend to teach visitors a formal lesson, but he does see the potential for artists and visitors alike to indulge in "some (serious) fun with the idea of creating and consuming hamburgers that are playfully engaging art history." The show also provides an opportunity for the Laundromat to display works from the space's rotating Flat File. Artists included in the File lend their work to the Laundromat for one year, after which the drawer may be offered to another artist. In this way, Curran hopes to increase the number of artists whose work may be viewed in the flat file, while simultaneously increasing the geographic diversity of the collection.

The Burger Group Show will be held at the Laundromat gallery on Saturday, August 8th, from 6-10 PM. Participating artists include Chris Deo, Sarah McDougald Kohn, Maria Walker, Jonathan Allmaier, Scott Wilson, Ben Godward, Joe Protheroe, Ianthe Jackson and Liz Atzberger. Conceptual burgers will be on sale for $5 to $20, and visitors are invited to take home a copy of the menu.

Growing up, I remember imagining that Berlin was located directly in the center of Germany. Thus the wall, whose existence we barely understood, was merely the manifestation of a line that ran the length of the country, spreading out from the city to the north and to the south. I also remember the day when my teacher sat us down to explain, as best she could, that the world had somehow changed, and that the biggest country on the map was now much smaller. In my head this was a hugely important development, indicating not only the immanent arrival of all new maps, but also promising big changes on those maps. Whole new countries. More colors. I was terribly disappointed when the new maps arrived and the changes seemed decidedly less than had been expected. I only bothered to learn the name of the biggest new country: Kazakhstan, while noting that Russia - which has always been its name in practice - still looked pretty big to me.

To this day I can't decide to what degree these youthful misunderstandings warped the reality of the situation. Berlin is certainly not in the center of Germany, but Russia still looms terribly large, both literally and figuratively. And the Berlin Wall, for its part, did run the length of the country, in a great many ways. Nejla Yatkin is an internationally renowned choreographer who grew up with the Wall in the way I grew up with those maps, as a consistent presence. Friday, at the Goethe Institute she will be leading a discussion about "how The Wall has affected all of us, and about how the lines between the personal and the historic can often blur." The talk begins at six, and is free.

Three questions for Ellis Gallagher, whose first solo show opens today at Collective Hardware:

ArtCat: Could you speak briefly about your work in relationship with everyday life?

Eliis Gallagher: My work is directly related to everyday life, the content and subject matter of my work are all items/objects we deal with on a daily basis.

I am simply putting works out there on the streets for people to enjoy publicly and also photographing my works to make prints - so people can enjoy them privately.

AC: Is there a logic to how you choose your objects? Do they present themselves in such and such a way?

EG: Sometimes there is a rhyme and reason behind which objects I work with, other times I like to randomly choose objects, in random geographical locations. It really depends on what is catching my eye at the moment; light source comes into play, as does color, dry/wet streets, chalk brand and location.

AC: Can you talk a little about the relationship between the objects themselves, your chalk renderings of them, and the images of said renderings?

EG: It is all related. The objects are already there and have always been there. I am enhancing these objects with chalk. The shadows of these objects. In situ, it is sculpture/installation. Be it public or private. Photographed. Prints can be made from the photographs, so it becomes a different medium.

Images from Margo Victor's film, The Rotten Riotous West, which opens tonight at Venetia Kapernekas.

Asylum: Inside the Closed World of State Mental Hospitals

The Urban Center, New York NY

Friday, July 10, 2009

Straitjackets, cavernous hallways with peeling paint, a title cast in a well-worn sensationalistic mold: the marketing for Chris Payne's Friday presentation at the Architectural League of New York set up a familiar sort of expectation for me. I knew what I would hear. The photographer, fresh from a day trip to one of the more convenient asylum-hulks in the area, would play up the Gothic-horror angle, show lurid closeups of bloodstained old medical equipment, insinuate that the place was haunted, then hawk his book to the audience. I, too, showed up, ready to do my part — scribble “Foucault” in my notebook, quote some old situationist to the effect that “the newest school buildings are indistinguishable from the newest prisons or the newest industrial complexes,” and so on.

The reality was a pleasant surprise. Payne is no idle urban explorer; his project involves the careful photographic documentation of state mental hospitals all over the United States. He has a genuine affection for these old spaces, not because of their creepy ambiance, but because they are the remnants of self-sufficient little communities that once enclosed everything from dairy farms to power stations. For Payne, they represent an echo of an America that once was — a place where things were still made, where homes were more than faceless condominiums. (He is an architect by training, so it is unsurprising that the real horror for him is the asylums' gradual destruction at the hands of condo developers.) His photographs are thus suffused with a peculiarly poignant kind of nostalgia; in many cases, the buildings they depict have already been demolished.

The state mental hospitals, he explains, were built between the mid-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, before psychotropic drugs and scientific psychiatry. (In fact, the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane was the precursor to the APA). In the absence of any reliable neurological treatment, the patients were offered complete isolation, natural surroundings and plenty of manual labor. At its height, the system housed over half a million people, the hospitals' farms and shops contributing to local economies throughout the country. In the postwar period, however, inmate labor was banned and a variety of new therapies made the asylums obsolete. Some still function; others are used as prisons or housing complexes, or simply stand empty.

The relationship between art and issues of the public, or the political has long been contentious. If the work is good, the thinking goes, why the additional qualification "public-art" or "political-art?" By demarcating a separate genre one creates different sets of rules for different kinds of art. This then reinforces the very boundaries which are often a target of artworks concerned with issues of the public and the private, in addition to absolving those works that otherwise would be seen as firmly supporting the status quo. These and other issues will be debated tonight at Eyebeam as part of their Summer School series. The presentation promises: "A rousing debate (with declaimed manifestos) from artists Hans Bernhard (Ubermorgen.com), and Patrick Lichty," Also in attendance will be Steve Lambert, (of last year's fake times and other strokes of brilliance) and Stephen Duncombe, editor of the much beloved Cultural Resistance Reader. The talk runs from 6 to 8 pm, and is free.

The French Revolution, which we celebrate today, is often taken in tandem with the industrial revolution as marking the birth of the modern world. If this is the case, it stands that modern art was decidedly late to the party. Sixty-six years late, to be exact, if we take Manet’s Olympia as the first document worthy of the descriptor. Here’s T.J. Clark on the subject: “Something decisive happened in the history of art around Manet which set painting and the other arts on a new course. Perhaps the change can be described as a kind of skepticism, or at least unsureness, as to the nature of representation in art.” In this rendering, the modern revolution in art does not immediately seem to resonate with what we understand of the French Revolution, taken here as the modern revolution in politics - in either timing or content.

The argument could be made, certainly, that those shopkeepers, rentiers, artisans and journeyman who sacked the Bastille two-hundred and twenty years ago today were displaying a pointed skepticism towards the nature of representation in politics; but ‘unsureness’ doesn’t really capture the spectacle of the same dancing around Paris with the Governor’s head on a pike. Perhaps the comparison is fruitless, and ‘modern’ is best understood to be a mere chronological indicator, employed by different disciplines to recognize decisive moments in their respective histories, but irreducible to any common essence.

The haunting of the theatrical avant-garde by its written texts makes contemporary art's reliance on the archive look incidental by comparison.There is good reason for this. Since performance combines so many different registers of representation at once, and all their attendant problematics, it requires that many more conceptual frameworks to support it. Few theatrical auteurs have seen fit to provide this documentation, and the most famous one, Artaud, provided only that, so far superior was The Theater and Its Double to any of his relevant theatrical practice. Richard Foreman, however, is a welcome exception to this tendency, making freely available his many notebooks and written works in relation to his more famous productions. Now, No-Body Zone, is taking one of these texts as impetus for creating an 'Exploding Audiobook' this Tuesday at Studio X. The performance attempts to grapple with the question "Can a media city-structure be built out of (Foreman's book No-Body) ?" The performance starts at 7, seating is limited and reservations are required.

Artist Warren Neidich has organized a day-long panel discussion taking place tomorrow afternoon at The Drawing Center. Present will be a diverse group of artists and writers including Keller Easterling, Boris Groys, David Joselit, Jonatan Habib Engqvist and others. The topic at the center for the convergence will be art and power, or, to risk begging the same question the event's title suggests, the power of art. It's something of a perennial concern for culture workers in a country where contemporary art -- and the liminal conversations that recede from its limits into neighboring disciplines -- remains steadfastly excluded from the national discourse. In a cultural field as comparatively cash rich, media enabled and internationally dispersed, it's no small wonder why it remains sequestered from the more fluid stream of popular culture. To creatively illustrate the point we may cite a myriad of quotidian metrics, from relatively low museum attendance rates in relation to other Western countries, to the phantom readership of the ever expanding realm of arts journalism, as deftly outlined by James Elkins in his 2003 book What Happened to Art Criticism?. But power, of course, as living thinkers from Rancière to Groys remind us, does not necessarily equate visibility or even the consolidation of bodies and wills in time and space -- even though the popular imaginings of its resistance remain fixed on these models. With a gentle insistence, then, our editors suggest tomorrow's panel to readers interested in these questions.

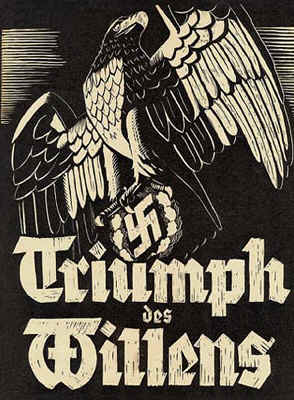

Somewhere towards the beginning of Leni Riefenstahl’s The Triumph of the Will, in the middle of a long and tedious sequence of military men addressing the party congress on matters of public policy, Goebbels, in a suit, rises to the microphone to speak about propaganda. “May the bright flame of our enthusiasm never be extinguished,” he says, looking somewhat more comfortable in front of the crowd then you might imagine. “It alone gives the creative art of modern political propaganda its light and warmth. From the depths of the people it rose aloft. And into the depths of the people in must descend… It may be good to have power based on arms, but it is better and more joyful to win and to keep the hearts of the people.” It’s a telling moment, especially in light of Riefensthal’s insistence, for the remainder of her life, that Triumph was not and is not a propaganda film, but instead a work of ‘total art’ or of ‘cinema verite.’ Technically speaking, she is correct, insofar as Hitler had chosen her precisely for her pedigree as an artist, and she only agreed to make the film when he promised to keep Goebbels and his minions at the ministry entirely out of its production.

And yet, watching the film today, it is clearly not only a piece of propaganda, but the apogee of the genre. By turns horrifying and deadly dull, it is wholly without irony or self-reflection of any sort. Quite literally a masterpiece, it is responsible for creating an entire arsenal of cinematic techniques later employed by everybody from Josef Stalin to Barack Obama. In effect then, the distinction, between art and propaganda, which mattered so much to Reifenstahl in the films production, has in some sense vanished. Art not only became propaganda but perfected it, the distance she fought to maintain damning her all the more for preserving the unique power of her vision. Triumph plays at Anthology this Saturday at 6 and 8:30, its worth seeing, if you haven’t before; even if the technical achievements no longer impress, the relentlessness of thing remains striking and, god willing, singular.

Mexican-born artist Teresa Margolles had built an impressive body of work interrogating the physical legacy of the deceased. She has, in the past, repurposed the water used in a morgue to wash corpses to makes bubbles, humidify a room, or simply let it drip from the ceiling. She has washed watercolor paper in the runoff from organic waste of dead bodies, and displayed the remains of a stillborn child, encased in a concrete block. In their immediate reception, each of these works first triggers a sort of physical revulsion; an almost palpable desire to flee. Once it becomes clear, however, that all necessary safety precautions have been taken - the viewer is left holding only their own superstitions and squeamishness, why this terrible fear of physical transference between the dead and ourselves? Further, Margolles draws on her own home, torn apart by the drug trade, to explore the ways in which the patterns of death and dying repeat the social inequalities of the living. Margolles will speak Thursday on this, and other topics, at the Museum of Modern Art. The talk begins at 6:30.

Shane Hope whose solo show, Your Mom is Open Source opened recently at Ed Winkleman, answered some questions via email about his work -

ArtCat: One thing that immediately jumps out to me about your work is its relationship to multiple regimes or paradigms of representation: linguistic and visual at bottom, conceptual, scientific, and mathematical in effect or by invocation. Can you talk about what takes place in the movement between these fields? To what extent does your practice, considered in sum, rehearse the sort of being-across-substrates detailed in the concept of transhumanism?

Shane Hope: My Mol Mods are plans for playground ball pits of pure operationality, all about ackles as atomic access-privs pictures, looking like line-art after lines of code, solving for sundry imaging inversions and a new fantastical-fodder faux naïve. The modeling files I design or manipulate to build drawings anticipate their own actualization via nanofacture, for the files are also plans for later manifestation of material objects. Precision placement of atoms is poised to become the new pen, so I participate in picturing projected possible puny places for us people. I've conscientiously chosen to work in customized versions of user-sponsored open-source molecular visualization systems as necessitated by way of analogy: we are artificially selecting for the hardware environments upon which we ourselves will run. My hand-drawn lines become vectors become atomic coordinates become novel carbon-based building blocks bootstrapping the next layer of life.

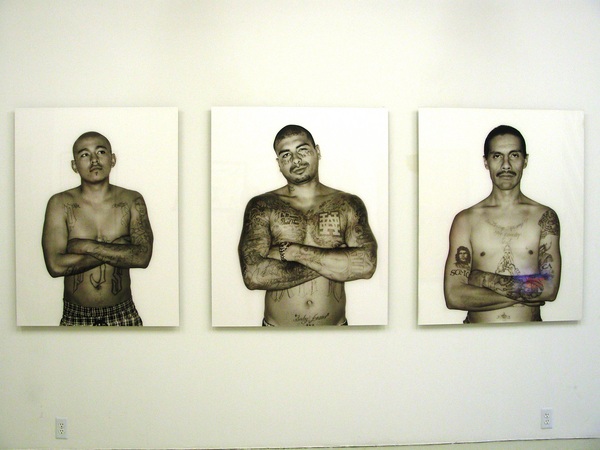

Tattoo at Kathleen Cullen Fine Arts is a multimedia exploration of tattoo art and its ever-changing role in society. The exhibition includes paintings, photography, sculpture and film, as well as a few empty bottles of Jack Daniels littered about the gallery for an something like an authentic, tattoo parlor feel. We caught up with Cullen, the director of the gallery, and asked about her inspiration for the show and her take on tattoo art.-- S.K.

Stephanie Korszen for ArtCat: What was your inspiration for situating the work of tattoo artists within the context of a fine art gallery?

Kathleen Cullen: The inspiration is really the everyday. You need only sit down at a café or bar, or stand at a traffic light, to grant your eyes the opportunity to admire the body art on others' skin. Additionally, one of the artists I represent, Max Snow, served as the catalyst for this exhibition. In 2008, Max documented the stories of Latino gang members in L.A., for whom tattoo art serves an important role in self-identity. Max also wears part of his identity externally in the form of body art.

In the 1930s, Herbert Hoffmann photographed people and documented their fantastic stories before they were sent to prison by the Third Reich. He developed a great respect for these people, whom he saw as hard-working and unpretentious. Many bore the simplest of tattoos on their arms and hands – historically a sign of degeneracy. Over the years, tattoos have broken free of this inherent link to all things degenerate, to the point where they now have the potential to serve as a status symbol on par with designer handbags. Bruce Willis, on the cover of W Magazine, sports tattoos. Supermodels adorn themselves with body art. We see biker motifs, as well as Maori, Japanese, and sailor themes – rich codes to decipher on other’s bodies.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian