This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

Features Archive

Asylum: Inside the Closed World of State Mental Hospitals

The Urban Center, New York NY

Friday, July 10, 2009

Straitjackets, cavernous hallways with peeling paint, a title cast in a well-worn sensationalistic mold: the marketing for Chris Payne's Friday presentation at the Architectural League of New York set up a familiar sort of expectation for me. I knew what I would hear. The photographer, fresh from a day trip to one of the more convenient asylum-hulks in the area, would play up the Gothic-horror angle, show lurid closeups of bloodstained old medical equipment, insinuate that the place was haunted, then hawk his book to the audience. I, too, showed up, ready to do my part — scribble “Foucault” in my notebook, quote some old situationist to the effect that “the newest school buildings are indistinguishable from the newest prisons or the newest industrial complexes,” and so on.

The reality was a pleasant surprise. Payne is no idle urban explorer; his project involves the careful photographic documentation of state mental hospitals all over the United States. He has a genuine affection for these old spaces, not because of their creepy ambiance, but because they are the remnants of self-sufficient little communities that once enclosed everything from dairy farms to power stations. For Payne, they represent an echo of an America that once was — a place where things were still made, where homes were more than faceless condominiums. (He is an architect by training, so it is unsurprising that the real horror for him is the asylums' gradual destruction at the hands of condo developers.) His photographs are thus suffused with a peculiarly poignant kind of nostalgia; in many cases, the buildings they depict have already been demolished.

The state mental hospitals, he explains, were built between the mid-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, before psychotropic drugs and scientific psychiatry. (In fact, the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane was the precursor to the APA). In the absence of any reliable neurological treatment, the patients were offered complete isolation, natural surroundings and plenty of manual labor. At its height, the system housed over half a million people, the hospitals' farms and shops contributing to local economies throughout the country. In the postwar period, however, inmate labor was banned and a variety of new therapies made the asylums obsolete. Some still function; others are used as prisons or housing complexes, or simply stand empty.

Shane Hope whose solo show, Your Mom is Open Source opened recently at Ed Winkleman, answered some questions via email about his work -

ArtCat: One thing that immediately jumps out to me about your work is its relationship to multiple regimes or paradigms of representation: linguistic and visual at bottom, conceptual, scientific, and mathematical in effect or by invocation. Can you talk about what takes place in the movement between these fields? To what extent does your practice, considered in sum, rehearse the sort of being-across-substrates detailed in the concept of transhumanism?

Shane Hope: My Mol Mods are plans for playground ball pits of pure operationality, all about ackles as atomic access-privs pictures, looking like line-art after lines of code, solving for sundry imaging inversions and a new fantastical-fodder faux naïve. The modeling files I design or manipulate to build drawings anticipate their own actualization via nanofacture, for the files are also plans for later manifestation of material objects. Precision placement of atoms is poised to become the new pen, so I participate in picturing projected possible puny places for us people. I've conscientiously chosen to work in customized versions of user-sponsored open-source molecular visualization systems as necessitated by way of analogy: we are artificially selecting for the hardware environments upon which we ourselves will run. My hand-drawn lines become vectors become atomic coordinates become novel carbon-based building blocks bootstrapping the next layer of life.

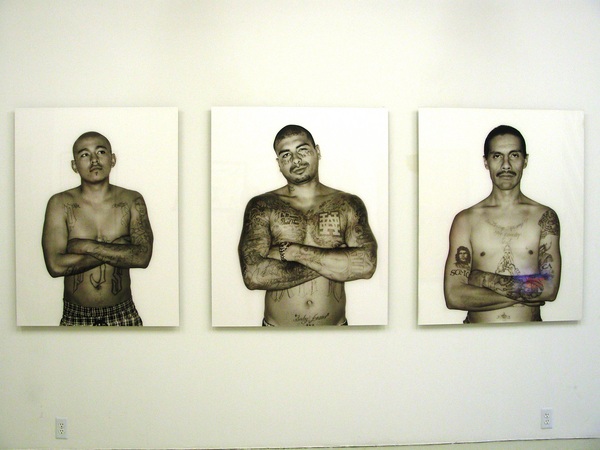

Tattoo at Kathleen Cullen Fine Arts is a multimedia exploration of tattoo art and its ever-changing role in society. The exhibition includes paintings, photography, sculpture and film, as well as a few empty bottles of Jack Daniels littered about the gallery for an something like an authentic, tattoo parlor feel. We caught up with Cullen, the director of the gallery, and asked about her inspiration for the show and her take on tattoo art.-- S.K.

Stephanie Korszen for ArtCat: What was your inspiration for situating the work of tattoo artists within the context of a fine art gallery?

Kathleen Cullen: The inspiration is really the everyday. You need only sit down at a café or bar, or stand at a traffic light, to grant your eyes the opportunity to admire the body art on others' skin. Additionally, one of the artists I represent, Max Snow, served as the catalyst for this exhibition. In 2008, Max documented the stories of Latino gang members in L.A., for whom tattoo art serves an important role in self-identity. Max also wears part of his identity externally in the form of body art.

In the 1930s, Herbert Hoffmann photographed people and documented their fantastic stories before they were sent to prison by the Third Reich. He developed a great respect for these people, whom he saw as hard-working and unpretentious. Many bore the simplest of tattoos on their arms and hands – historically a sign of degeneracy. Over the years, tattoos have broken free of this inherent link to all things degenerate, to the point where they now have the potential to serve as a status symbol on par with designer handbags. Bruce Willis, on the cover of W Magazine, sports tattoos. Supermodels adorn themselves with body art. We see biker motifs, as well as Maori, Japanese, and sailor themes – rich codes to decipher on other’s bodies.

Earlier this spring I had the pleasure of touring New Orleans with two art and architecture historians from Tulane University. We of course spent a significant amount of time wandering the Lower 9th Ward, gawking at the rescue hieroglyphics spray painted on abandoned houses, and generally participating in what seems to be the booming industry of trauma tourism. But we also found time for art. In particular, we spent part of one afternoon with KKProjects, an exhibition space composed of six previously abandoned houses in the St. Roch neighborhood.

Founded by Kirsha Kaechele, KKProjects offers each of its spaces for three-month site specific installations, working with local, national, and international artists to develop locally-integrated, conservation-focused work. Currently on view at KKProjets is Knead, an urban farm/sustainable living project, and Safe House, a home converted into a giant safe that stores Mel Chin’s ongoing Pay Dirt. Both projects purport to engage local concerns. Pay Dirt invites participants to draw their own “fundred dollar bill” in an effort to amass 300 million of these fake notes to exchange with congress for $300 million of the real thing—the estimated cost to clean the lead out of New Orleans’ soil. Across the street, Knead hosts a backyard garden and what looks like a strange indoor jungle gym, though on explanation turns out to be a human-powered bread maker. Participants swing from poles to grind corn, which piles up on the floor to be collected by the gallery attendants and eventually turned into bread.

The International Studio & Curatorial program, a former warehouse wedged conveniently in East Williamsburg next to an egg factory and a few fungus-like new condos, is the perfect place to serve as host to visiting artists and curators. Not too big, the space has only a few galleries open to the public while the rest of thie building is home to studios for international artists in residency for the year. Inviting and manageable, this charming space held an intimate evening of performances by artists who incorporate music into their work, or did so at least for Hear Myself In It an evening of music set against the current exhibition up at ISCP titled On the Tectonics of History.

At NURTUREart’s exhibition for the Bushwick Biennial, the intent is to focus on “utopia, urban change, and the role of a place in artistic identity” but the resulting show is dreamier and niftier than those themes might imply. Entering the gallery made me imagine walking into a human-sized, contemporary version of one of Joseph Cornell’s boxed assemblages.

Going upstairs to the show is a gradual, gentle process, beginning with the trailer parked outside the building, which houses a garden complete with a pond and love-seat length bench (there is a tiny, even cuter prototype of Kim Holleman’s work, Trailer Park, in the gallery itself.) The show is sandwiched by gentle, repetitive pieces – the stairs leading to the space play host to Escalator Helix Vertical, an animated illustration of spinning escalators, and the gallery’s adjacent rooftop is covered with Audrey Hasen Russell’s Beam Tower with Pink Grass, which is what its name implies – coils and coils of cotton-candy-colored pink foam which have been cut into spiky forms to look like grass.

I really liked this show, though I expected not to. My last experience with earnest-seeming art in Bushwick was…I can’t remember when. I may have never seen it before. Benjamin Evans, who curated the show for NURTUREart, has done an incredible job of putting together something appealing, and sometimes even cute (be sure to see The Farthest City, by James Reeder – it’s a charming wall-mounted utopia) that still maintains a sense of humor and a healthy sense of dignity. A perfect example is Fallen, Jonathan Brand’s prone fiberboard bicycle. The life-sized, super-accurate apparatus lies on the gallery floor in front of three petite drawings depicting a biker in various stages, the last of which shows him on the ground next to his similarly horizontal bicycle. The drawings are sweet, and they’re funny, and they’re good. Please go see this show. Its so nice to encounter work that is simultaneously compelling and funny.

This Saturday marks the opening of the inaugural Bushwick Biennial. Four Bushwick-area spaces will be showcasing the work of local artists – NURTUREart Non-Profit, Pocket Utopia, English Kills, and Grace Exhibition Space. We have spoken with artist Austin Thomas, director of the art and social project Pocket Utopia. For the Biennial, Pocket Utopia will be exhibiting the work of eight Bushwick-area artists in the space’s last show of its two-year run, “Finally Utopic.”

ArtCat: I understand that this is the inaugural Bushwick Biennial. Can you speak a little bit about what it means for this area of Brooklyn to stage a Biennial?

Austin Thomas: There's definitely a local flavor to this Biennial – that local flavor being Bushwick. There's a lot of creative energy and diversity in the Bushwick art community. All the spaces in the Biennial are "alternative," meaning they're artist-run, no-profit, performative and rad!

Blanks, Templates, Undos, Redos, Matt Sheridan Smith's debut solo exhibition at Lisa Cooley, is comprised of opaque sculptures and drawings which occupy a vague, transitional territory despite their resemblance to several ubiquitous forms in present day work-life.

The show's sole video, Untitled (open/shut), 2008 (all other works 2009) is a seven-minute montage cut from footage of actors opening and closing doors in Robert Bresson's film, L'Argent (1983). In Smith’s edit, the characters endlessly pass into and out of boutiques, cafés, homes, offices, and other spaces. Departing prompts removed, we’re given the momentary silence of a door swinging ajar, over and over again. Smith’s projection is a figural representation of his blanks, templates, undos, and redos; transitions that never lead anywhere but serve to personalize the concepts of banality operating within the other works on view.

Freedom and Beauty: The Art of Iraqi Refugees

St. Paul the Apostle - 405 W 59th St, New York NY

30 April - 28 May 2009

Everyone's talking about faith these days. In a recent issue of Commonweal, Terry Eagleton suggests that we ought to be attentive to the critical potentialities of religion; they are crucial, he thinks, because they provide an alternative to both radical fundamentalism and liberal-rationalist dogmatism. In a sense, it's easy to see what's at stake for him. Religion as a field of study now fills a niche once occupied by certain varieties of Marxism: it is, paradoxically, an ideologically uninvested space where adventurous approaches are welcomed rather than shunned. If its appropriations of Heidegger and Badiou are occasionally unrefined, it is because it's still something of a critical frontier.

The exhibition Freedom and Beauty: The Art of Iraqi Refugees, on view this month at St. Paul the Apostle Church, brings this frontier quality immediately to mind. Its engagement with theory, to be sure, is minimal. Nonetheless, the aggressive way in which it breaks with curatorial common sense is something of a statement in its own right. Paintings by four artists are arranged on a single display stand, crammed sardine-like into a few square feet. (Another artist is displayed on a slice of adjoining wall). The accompanying exposition in the press release and wall texts spends vanishingly little time on the paintings themselves. It focuses, rather, on the circumstances of their production, as even the title suggests. It describes the artists' experiences in war-torn Iraq and emigration, positioning the work itself as merely a response or an expression of the crisis — anything but l'art pour l'art.

But just as it makes little effort at any move towards something like contemporary exhibition practice, the exhibition also avoids making explicit political statements — it identifies neither culprits nor solutions — and, more strikingly, proselytizing. The objective seems to be the establishment of an interspace between traditionally ecclesiastical, artistic, and political sites and styles of dialogue. Though perhaps this is a grand claim for what is, after all, a fairly modest undertaking, its organizers are hardly strangers to such projects: the exhibition is the work of the Paulists, a missionary order that sees new media and cross-cultural exchange as fundamental to its evangelism. Freedom and Beauty, in short, represents a kind of religion even a Marxist like Eagleton can approve of. It is hard not to applaud the effort or appreciate its undermining of the borders between cultures and professions.

Michelle Lopez - The Violent Bear It Away

21 March - 17 May 2009 at Simon Preston Gallery

301 Broome Street

A conversation with artists Michelle Lopez and Andrew Cornell Robinson that took place in both of the artists’ studios in Bushwick, Brooklyn on 7 April 2009.

Andrew Cornell Robinson: When you went to California there was a shift in your work. In fact there seems to be several moments when your work has undergone significant shifts in attention and focus evidenced by the materials you use and your conceptual concerns.

Early on you started to work with leather, which became your signature material. Much of your work has had this intense exploration of material. What’s that about?

Michelle Lopez: Back in grad school, I was working with chocolate, and apple skins. I was trying to find a way to re-contextualize a material, something that was incredibly familiar to us. In a way the work is about how to invert something that is masculine and make it feminine, create this ambiguity. The thing that I am interested in most, is exploring androgyny. In terms of my education, I was interested in a feminist perspective, but I wasn’t really interested in a feminist aesthetic.

AR: What do you mean, like Judy Chicago?

ML: I was interested in feminist theory but not entirely convinced by the art, well yeah Judy Chicago, like all of the artists associated with early feminism.

ACR: A friend of mine calls that aesthetic “My Tortured Vagina” art.

ML: (Laughter) Exactly! So in a way I wanted to create work that was specifically non-gendered. For me it’s really hard to talk… I don’t want to be specific about the language. I feel like I can so easily get pinned down, and I don’t want to, so it’s better for me to keep the ideas open.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian