This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

Recently by Joshua Johnson

If Love Could Have Saved You, You Would Have Lived Forever

Bellwether Gallery - 134 Tenth Avenue, New York NY

10 July - 8 August 2008

Then there is this civilizing love of death, by which

Even music and painting tell you what else to love.

[…]The people who dig up

Corpses and rape them are I understand not reported.

--William Empson, Ignorance of Death

Ours is a culture that moves quickly. Obsessed with youth, we gaze at the horizon, waiting for the next sun to rise and leave the past to molder away in its tomb. When we do look back, it is with a ghoulish disposition, as if to resurrect the quiet bones of some dead saint and make them dance again. If Love Could Have Saved You, Then You Would Have Lived Forever, at Bellwether Gallery examines this disposition and passes through it to look at the way that the objects of death contribute to our lives. Curated by the gallery’s owner, Becky Smith, the show draws from Ms Smith’s own private collection of memorial artifacts and similarly themed works from contemporary artists.

The impulse to collect the objects of death is one that winds its way throughout the show. As Walter Benjamin wrote, "The most profound enchantment for the collector is the locking of individual items within a magic circle in which they are fixed as the final thrill, the thrill of acquisition, passes over them." And what could be more final than death? Even it may be fetishized and inscribed within the collector's narcissism. There are the Joss paper effigies, paper re-constructions of real items, Victorian hair wreaths, floral tableaux woven from the hair of a dead loved-one, and collected images of blank grave-markers, used to sell gravestones. Rob Hauschild presents a book of photographs depicting roadside memorials, while curator Becky Smith presents her personal collection of photos of unmarked headstones. Like Gogol’s Chichikov from Dead Souls, the collector of death attempts to make their way to life through the remains of the dead.

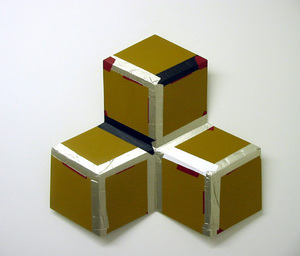

The State Itself Becomes A Super Whatnot

Liam Gillick

Casey Caplan - 525 West 21st Street New York, NY

8 May 8 - 14 June 2008

Recent economic and political crises, such as the sub-prime mortgage fiasco, have called attention to the problematic position of the nation state in contemporary global culture. The current American recession, whose genesis lies in the unprecedented growth of liquid capital in the global marketplace, and a complex series of obscure banking and investment strategies, has ended with United States government propping up investment capital, such as Bear-Sterns, in an effort to avoid a projected global meltdown. The oft-repeated explanation was that Bear-Sterns was "too big to fail." That is, its connections with the global marketplace ran so deep that a collapse of the company would set off a domino effect, wreaking worldwide financial havoc. The government must therefore protect this corporate citizen, or risk endangering its own position of power. The penetration of global capital into the apparatus of the state leads one to ask whether or not it is the tail that wags the dog. Liam Gillick raises some of these issues with The State Itself Becomes A Super Whatnot, his new solo show at Casey Kaplan Gallery. Gillick has made a career of repurposing minimalism and conceptualism into neatly designed objects embedded in complex theoretical narratives that are dispersed through the artist's prolific writings, performances, and talks.

His biggest formal debt is perhaps owed to Donald Judd, whose works Gillick’s on view here most resemble, and whose overbearing critical practice is evoked by Gillick’s complex theoretical interpretations of his own work. Unlike Judd’s criticism, which was always intended as supplemental to what he considered his actual artistic production, Gillick’s critical and theoretical writing is an essential element of his artistic practice. In blurring the lines between artistic production and the disinterested gaze of the cultural critic he reveals that the motivations and strategies of the critic are as much an act of creative agency as that of the artist himself.

To that end, he has created the long running potential, or unwritten, text, Construcción de Uno. This unwritten text never completely reveals the artist’s intentions, but positions a hermeneutics whose unquantifiability acts as a buffer for those critics who would seek to reduce the artist’s practice to their own terms. He has revealed a few details about this text, however: one of the principle scenarios of the text, whose narrative frames this exhibition, follows the former workers of an experimental Volvo manufacturing plant located in Brazil who return to the workplace after it has been decommissioned by Ford. There they spend their time producing elegant theories on labor equivalence and begin to refashion the site as a testing ground for new models of production.

Forever the Management of Magic

Luc Tuymans

David Zwirner - 525 W 19 St, New York NY

14 February - 22 March 2008

W. G. Sebald begins one of his essays with a quote from Michel Foucault:

We must therefore listen attentively to every whisper of the world, trying to detect the images that have never made their way into poetry, the phantasms that have never reached a waking state. No doubt this is an impossible task in two senses; first because it would force us to reconstitute the dust of those actual sufferings and foolish words that nothing preserves in time; second, and above all, because those sufferings and words exist only in the act of separation.

Sebald, a German writer who came of age in the trauma of post-war Germany, produced works that meditated upon memory, both collective and personal. His seminal work, Austerlitz, follows its principle character, adopted as an infant, as he travels Europe, examining its Architectural monuments and hoping to uncover the elusive mystery of his parentage. Through a blend of fact, fiction, philosophical insight, and photographic records, Sebald weaves a melancholy tale that ultimately traces the horror of the holocaust through records and the very architecture marking the land like monuments of the dead.

Luc Tuymans, a painter of moribund and starkly hued images, also believes that the objects of history are never free of the haunting traces of memory. His paintings, like Sebald’s perambulatory tale, raise the holographic insistence of a reality that surrounds the comfortable knowable images of our world with the ghosts that once imbued them with life and even death. To appropriate a phrase of Balzac’s, they are "a perfect image of the past, a symbol of something great now destroyed, a poem."

That is not to say that Tuymans focus is never in the present. If anything, his work is arguably opportunist. His last show at David Zwirner in 2005 was occupied by an examination of contemporary American power. The seminal images of the show, one pursed lip portrait of Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and another of a demolished building, both literally and figuratively addressed the stresses of American power post 9/11.

YARDSALE

Jade Townsend

31 January - 8 March 2008

Priska Jushcka - 547 W 27 St, New York NY

Jade Townsend creates installations and sculptures with a theatrical flare. His works are often like stage sets, constructed complete with props and scenery. What they seem to be lacking are the actors; which is, of course, where you, the viewer appear. Townsend invites you to wander across the stage and read the script that is everywhere in the work.

When it works, like Townsend's installation last year at Priska Juschka, and when the days fly by on their own, the elements he assembles line up like a well cast play. That work, which first confronted viewers with a prison-like façade, was broken open to reveal a white desk, chair, and small, comfortably suburban reading lamp. Above this desks was a window that looked out onto a miniature room, built in a forced perspective that ended in another window, peering just over the horizon of a model landscape. Outside again, and behind the brick room a barbed wire fence contained the miniature view, while behind the construction were several large trash barrels containing scrap wood and axes nestled in false flowers with the inscription "unlearn."

Taken all together the work suggests Foucauldian prison themes, the Abu Ghraib scandal, but also security, its limitations, and its inhibiting tendencies. More broadly, the work pointed to the impediments to altering one’s perspective and the need to question and even destroy perceived truths in favor of freedom of thought. The installation managed to feel not only topical, but also mined universal themes that transcended a narrow political interpretation.

Therefore, my expectations were high when I came to view Townsend’s new installation at Priska Juschka, YARDSALE. The title of this exhibition has an especially auspicious prescience when compared to the artist's previous efforts — whereas the last show title was written in a subtle lower case font and almost formed a complete sentence, YARDSALE is a single word delivered in heavy-handed capital letters.

Alex Hubbard at Nicole Klagsbrun

Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery – 526 W. 26 St, #213, New York NY

17 January – 16 February 2008

"...the genius of comedy was the same with that of tragedy, and that the true artist in tragedy was an artist in comedy also." --Plato, The Symposium

Skewering the bold ambitions of modernism has become par for the course amongst contemporary artists. Aaron Curry mixes forms from Noguchi, commercial design, and graffiti, while Banks Violette has gotten quite a bit of mileage out of mashing minimalism and death-metal nihilism. Alex Hubbard takes a much more punk rock approach with his chaotic and playfully destructive exhibition at Nicole Klagsbrun.

In a previous exhibition at the Whitney at Altria in 2006, one of Hubbard’s video works had meticulously documented the processes of a methamphetamine fabrication lab. At Klagsbrun, he turns his hand to the more abstract processes of creation and destruction with several new videos and paintings. The latter are clearly derived from the former, almost as if they were artifacts recovered from the artist's more interesting work on the two monitors installed in the gallery. A monitor across from several paintings loops three videos from the Collapse of the Expanding Field II series, while a larger monitor, in a separate room prefaced by an oil painting of floating ribbons, displays two other videos.

27 x 27 x 4 inches.

Courtesy Winkelman Gallery.

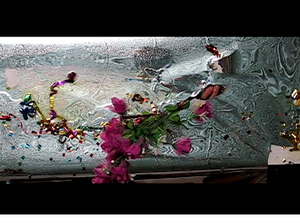

50/50

Ivin Ballen

Winkelman Gallery - 637 W. 27 St., New York NY

29 November 7008 - 5 January 2008

The more modest materials of artistic practice occasionally come under the purview of the artist and are elevated to the status of art. In the 70s, when Rauschenberg was short on materials, having just moved from New York to a small island near Florida, he looked around his studio and saw the clutter of packing supplies and other detritus. He took immediately to what was at hand, and the Cardboards, a series of works made from simple cardboard boxes, were born.

New York artist Ivin Ballen was also struck with a similar revelation: while transporting several of his earlier works across country, he looked in the back of his car and found the works, wrapped in plastic and cardboard, transformed.

Ballen set about investigating this new vision, and while his paintings are immediately reminiscent of those shocking Duchampian works of Raschenberg, they are anything but ready-made. Ballen’s process involves building a maquette from humble materials, casting them in fiberglass or resin, and painting them with trump l’oeil finish.

At first glance the effect is convincing, and without close scrutiny the objects appear to resemble so much contemporary art (see: Un-monumental at the new Museum) with their wacky assemblage construction. Upon inspection the paintings reveal elements of their process. “Tape” impresses rather than exudes, depths become protrusions, and the whole is a negative of its model. This reversal is characteristic of Ballen’s work—here the ready-made is actually the constructed—and more Étant Donnés than Fountain.

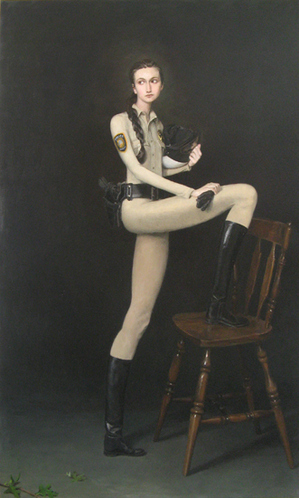

Jansson Stegner

15 November - 22 December, 2007

Bellwether Gallery - 134 Tenth Ave, New York NY

The way in which an artist chooses to depict their subject usually says as much about a subject as the subject itself. Jansson Stegner’s recent exhibition at Bellwether is indicative of this statement. Stegner’s subjects, police officers, are portrayed in a mannerist style, lounging in ideal naturalistic settings.

That mannerism is one of the first notable features of this work, and its historical pedigree lends his paintings their conceptual heft. The sixteenth century mannerist period dovetails nicely with the current state of the art world in the midst of high American imperialism — the printing press revolutionized media, commerce was expanding on a global scale, and the changing religious environment led to political and cultural strife. Art was changing too; the classical canon was abandoned, and artists began to stress intentional distortions. Arguably, we face a similar situation today in which the modernist canon has been abandoned for post-modern deconstructions.

Obviously Stegner is not the first to revisit this form; the figure of John Currin hangs over this exhibition with an uncanny sense of déjà vu. Both Currin and Stegner appropriate the formal devices of mannerism to point to the decadent state of art and culture. Whereas Currin makes a more ambiguous gesture towards the lifestyles of a carefree and privileged bourgeois, Stegner is much more politically explicit, choosing the police as his subject. His figures — like that of the young woman in Let Your Loveliness Fade As It Will, who stands contrapposto tying her long blond hair in a pony tail — are tender, seductive portraits of a vulnerable power.

In his last solo exhibition at Mike Weiss Gallery, Stegner portrayed his subjects, also dressed in police uniforms, in a variety of violent and taboo situations, such as a reckless motorcycle accident and a casual woodland orgy. His brushwork had a charming awkwardness, depicting just enough information to direct the viewer towards the broad outlines but leaving them to fill in the gruesome details. Those paintings had a sense of urgency, a personal involvement with a disordered and complex state in which his figures struggled.

This show leaves behind that expressive brushwork and personal touch, and moves towards a more aloof statement. Stegner’s brush no longer seems to battle with his characters, but historicizes them with a sense of psychological detachment. Throughout the show, Stegner maintains a singular format, his hot cops lounge idyllically, alone, their gaze averted and introspective. These figures betray their humanity and our self-recognition. Looking at these pictures might feel like looking at a display case in the Museum of Natural History: the animal has been stilled in a pose that only mimics the life it once had.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian