This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

If Love Could Have Saved You... at Bellwether

If Love Could Have Saved You, You Would Have Lived Forever

Bellwether Gallery - 134 Tenth Avenue, New York NY

10 July - 8 August 2008

Then there is this civilizing love of death, by which

Even music and painting tell you what else to love.

[…]The people who dig up

Corpses and rape them are I understand not reported.

--William Empson, Ignorance of Death

Ours is a culture that moves quickly. Obsessed with youth, we gaze at the horizon, waiting for the next sun to rise and leave the past to molder away in its tomb. When we do look back, it is with a ghoulish disposition, as if to resurrect the quiet bones of some dead saint and make them dance again. If Love Could Have Saved You, Then You Would Have Lived Forever, at Bellwether Gallery examines this disposition and passes through it to look at the way that the objects of death contribute to our lives. Curated by the gallery’s owner, Becky Smith, the show draws from Ms Smith’s own private collection of memorial artifacts and similarly themed works from contemporary artists.

The impulse to collect the objects of death is one that winds its way throughout the show. As Walter Benjamin wrote, "The most profound enchantment for the collector is the locking of individual items within a magic circle in which they are fixed as the final thrill, the thrill of acquisition, passes over them." And what could be more final than death? Even it may be fetishized and inscribed within the collector's narcissism. There are the Joss paper effigies, paper re-constructions of real items, Victorian hair wreaths, floral tableaux woven from the hair of a dead loved-one, and collected images of blank grave-markers, used to sell gravestones. Rob Hauschild presents a book of photographs depicting roadside memorials, while curator Becky Smith presents her personal collection of photos of unmarked headstones. Like Gogol’s Chichikov from Dead Souls, the collector of death attempts to make their way to life through the remains of the dead.

Many elements of the show bear the mark of the respective milieus from which they arrive; that is, they weren't created purely for an aesthetic reflection of death, but as works for remembrance, ritual, and commerce. They are pragmatic in their relation to death, objects with a clear purpose. Joss paper, for instance, is a token of ancestor worship in the Chinese Taoist tradition. It initially appeared as a special type of money to be burned for ancestors to use in the afterlife, but its use has since evolved to include contemporary objects such as electronic devices and name brand clothing. Ms Smith and Mr Hauschild have collected a number of these objects and arranged the effigies on a series of shelves, where the dizzying accumulation recalls the packed aisles of a big-box shopping center. Candy colored paper cell-phones glint in cellophane packaging, where they are placed by foil accented paper boom-boxes, which themselves are stacked near other reproductions of various gaudy desirables. Many of the effigies are based on Western consumer goods and luxury items; their use in traditional Chinese funeral ritual is both a witness to the influence of consumer culture and a sly visualization of the ephemeral nature of its products.

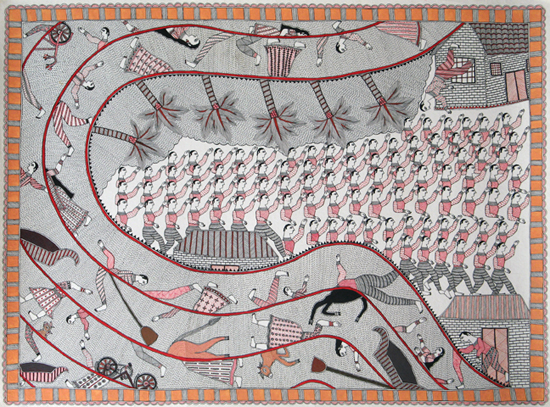

The globalization of mourning is also apparent in the work of Leeli Devie and Amrita Das. Both artists work in the Mithila painting tradition, a distinctive folk art from Northern India that emphasizes delicate line-work and pattern, but the images included in the show reference the tragedies of 9/11 and the Sri Lankan Tsunami of late 2004. The fluid use of line and dense imagery captures not only the flurry of disaster, but also weaves together suffering of the peoples depicted in the paintings, becoming a tragic event history alternative to the widespread and electronically produced media coverage the Tsunami received upon its impact.

"Death is all metaphors, shape in one history," as Dylan Thomas said. It is a truism that escapes neither kin nor kind, as Roy Kortick recognizes in his memorial to his lost dogs that died on 9/11. Mr. Kortick, whose work has a folksy-homemade feel, here works in ceramics and mixed media. The piece, a hodge-podge shrine of eccentric relics and miniature surreal sculptures, conjures the workshop of a mad apothecary. It is our memorials to the dead that help heal the rift that is left in the wake of their passing. Kortick seems here to be saying that death is more than an inheritance; it is also a place for us to celebrate our common humanity, however solemn that celebration may be.

The photographs of Lisa Ross examine the mourning rituals of other cultures; in particular, the stick and cloth built burial mounds of the ethnic Uyhgur people of China. The Uyghurs are primarily Islamic and have faced persecution since 9/11 by the People’s Republic of China under the pretext of the war on terror. As the PRC gains in economic power, a unique cultural identity may rapidly disappear. Ross’ photographs -- solitary, arid shots of spindly, scrap decked bundles in the desert -- are like the remainders of a tree plucked bare. These images are themselves a memorial to a culture whose very existence is threatened. It is a reminder that while death may be the fate of everyone, it is the living who control the fate of the dead.

It is this very problem that Patricia Cronin’s Memorial to Marriage, a sculpture of two women embracing, seeks to address. The work, classically sculpted and cast in the eternal medium of bronze, is meant as a grave marker for the plot she has reserved with her partner Deborah Kass. Only time will tell whether they too will be allowed to rest in peace.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian