This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

Kohei Yoshiyuki at Yossi Milo

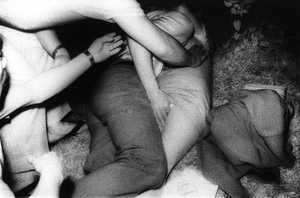

Courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery.

Kohei Yoshiyuki

Yossi Milo Gallery - 525 West 25th Street New York, NY

6 September - 20 October, 2007

If you have read anything about Kohei Yoshiyuki’s show The Park, currently on view at Yossi Milo Gallery, you know the basic story — that Yoshiyuki went about photographing young lovers coupling in Toyko’s public parks and the many men who watched them do it. As told to The New York Times columnist Philip Gefter, the story goes that one night in the early 1970’s while innocently photographing lit skyscrapers, Yoshiyuki strolled through a local park and happened upon a group of men secretly watching a couple fool around. The couple seemed unaware of the rapt audience and went about their business unperturbed. Intrigued, Yoshiyuki decided to shift the focus of his camera lens away from the steel phallus to real phallus. After spending months infiltrating and observing these clandestine gatherings sans camera, Yoskiyuki began documenting the events without disrupting the lovers or the peeping toms, using a film camera outfitted with an infrared flash.

The Park series captures two of photography’s most salient characteristics: photography is both a documentary and voyeuristic medium. The original presentation of The Park focused more attention on its voyeuristic aspect than does the show at Yossi Milo. When Yoshiyuki showed the work in 1980 he printed the photographs wall sized, turned off the lights in the gallery, and equipped gallery goers with flashlights to view the images in order to replicate the experience of being in the park — he was quoted in The Times saying that he wanted viewers to have to look at the bodies “inch by inch.” For this show he printed the images at a modest 16 x 20 inches and displayed them documentary style, in a neat line, one abutting the other. Though this show is less salacious than its predecessor, the original presentation was more honest about the audience’s relationship to the photographs. The act of looking at these photographs is voyeuristic. We should revel in that, not pretend as if we can maintain a cool distance.

The grainy, slightly blown out, black and white images look and feel like they could be printed in a newspaper. They are sloppy, the horizon line dips and sways, and the composition is often hurried and cluttered — we imagine that Yoshiyuki had to snap the pictures quickly in order to escape undetected. And, though the content is certainly lurid, there is nothing sexy about the photographs. In fact, everyone is at least partially, if not fully clothed, and the most explicit sexual act is of one man felating another, shot from a much greater distance than the majority of the heterosexual rendezvous.

Courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery.

Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery.

What is interesting about these photographs is not that they show us anything that we are surprised to see in this day and age. In the intervening thirty years since Yoshiyuki shot this series, contemporary fine art photography has been deluged with images that make us aware of all the unusual, dark and strange places in which lovers make love. Larry Clark, Nan Goldin, and Ryan McGinley (to mention but a few) have shown us couples, threesomes and groups cavorting in the back seats of cars, on couches at crowded parties, in swimming pools, up in trees, in bathtubs, on subway cars, and on city streets. People love to do it in all kinds of ways, with all kinds of people, in all kinds of places.

What is valuable about seeing Yoshiyuki’s work — other than admiring them for their weird, spooky beauty and the insight they give us into this specific aspect of Japanese sexual culture — is that the photographs implicate us, the viewers, in their voyeurism. They question the pleasure we derive from viewing similar images that frequently line Chelsea gallery walls. By pairing images of intertwined young lovers in their floral beds, with images of the perverse men who watch them, Yoshiyuki holds up a mirror and forces us to ask: how different is the photographer or viewer from those men? Does filtering our acts of voyeurism through the camera really render the act art and not crime? Is distance in location and time to the act enough to distinguish a fine art connoisseur from a peeping tom? Go take a look, but be forewarned that your hands may not feel clean.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian