This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

Art and Porn: Towards a Progressive Dialogue

Women in Experimental Film

Co-presented by The Film-makers’s Cooperative and PS1

2pm Saturday 1 March 2008

PS1 - 22-25 Jackson Ave, Long Island City NY

Women Behind the Lens, Panel Discussion

Presented by CineKink

Moderated by Rachel Kramer Bussel

5pm Saturday 1 March 2008

Anthology Film Archives, New York, NY

1965, color film in 16mm, 22:00 minutes

Running concurrent to the WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution exhibition at PS1 and boasting its own set of events, was the less high profile CineKink Film Festival. The festival, whose aim is to continue "the recognition and encouragement of sex-positive and kink-friendly depictions in film and television" — according to the letter of introduction written by CineKink Co-Founder and Director Lisa Vandever — focuses primarily on porn, a topic deplored by many feminists, yet one that resonates deeply with much of the work on display at PS1.

Saturday March 1, 2008, in a moment of programmatic convergence, PS1 in Long Island City screened the works of seven experimental feminist filmmakers followed by a panel discussion; across the river at the Anthology Film Archives, CineKink hosted its pornographic version of the same event, showcasing woman-directed works of pornography followed by a panel discussion with the filmmakers.

The Women in Experimental Film screening at PS1 featured films made by feminist filmmakers Barbara Rubin, Marie Menken, Carolee Schneemann, Barbara Hammer, Marjorie Keller, Peggy Ahwesh and Abigail Child. Of the seven films screened, three films dealt with sexuality and sexual encounters explicitly, and a fourth one focused entirely on the mechanisms of the body.

Barbara Rubin’s Christmas on Earth involved a simultaneous double projection, one larger and the other half its size, superimposed on top of one another. According to an essay by Daniel Belasco published by Art in America, the 29-minute film is the "record of an orgy staged in a New York City apartment in 1963." The larger image consisted primarily of images of female and male genitals, and close up shots of couples making love. The smaller projection showed the participants' entire bodies. Rubin imbued both projections in hues of deep red and purple paint. When creating The Color of Love and Covert Action Is This What You Were Born For? artists Peggy Ahwesh and Abigail Child, respectively, spliced together found footage that consisted of both professional and amateur pornography. In both films, the heavy editing and deterioration of the film upsets the narrative, such that images become surreal and disconnected and cease to read as traditional pornography.

The event also showcased Carolee Schneeman’s Viet-Flakes, a unique film in her oeuvre for not containing any sexual material, as well as Sanctus by Barbara Hammer, whose body of work includes a number of erotic lesbian works. Currently, Schneeman’s 1965 erotic film Fuses is running continuously for the durations of the WACK! Exhibition. This work is a dense, colorful and loopy 18-minute montage of Schneemann and her then lover James Tenney making love. The work is intimate and beautifully layered with images of Schneemann running into the waves and a literal coating of paint smothered onto the film-strip.

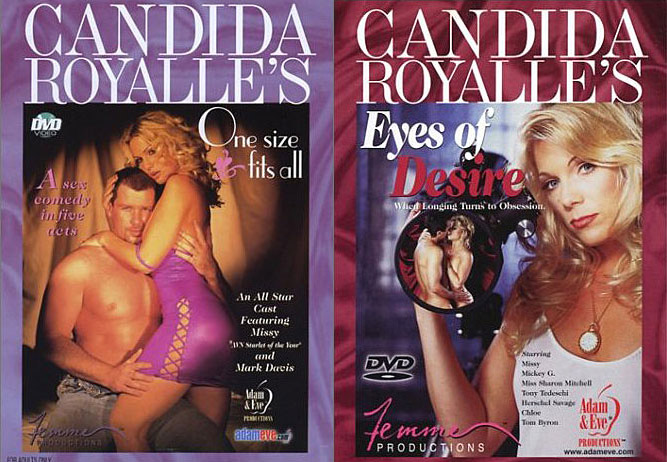

All five of the films in the "Chick Flicks" showcase were appropriately erotic. Shorts by Erika Lust, Petra Joy, Madison Young and Anna Span were screened. Because the two events ran simultaneously, I was only able to see the experimental film screening and women porn directors panel. Before the panel began, CineKink showed clips of feature length productions by panel participants Julie Simone, Audacia Ray and Candida Royalle. Candida Royalle showed a montage of her films The Gift, One Size Fits All, and Eyes of Desire, edited with production footage and interviews with Royalle. The clip of Audacia Ray’s film The Bi-Apple, featured a uniquely inter-racial cast engaging in all manner of hetero- and homosexual activities.

Attending the two panels one after the other inspired me to wonder what distinguishes the pursuits of these two sets of women filmmakers. In particular, considering that a number of the women are working towards positive representation of female sexuality on film, why are they not and why should they not be read against one another? What pragmatic, aesthetic or narrative distinctions render one art and the other, well, porn? Why is it libel to label Schneemann’s work porn and seemingly ridiculous to call porn, art? Is real sex the exclusive terrain of the porn industry? And is there anything to gain from a comparison?

From my view, there are three dominant cultural distinctions between erotic experimental films and pornography. First, porn is intended to illicit sexual pleasure in the viewer, while art is usually made for more cerebral purposes. Second, porn is intended for a broad, popular audience and experimental film for reasons of distribution or artistic prerogative are not. And third, experimental film is often intended to reveal some human truth, while porn is strictly fictional.

The aesthetics of the productions, of course, do vary greatly: most of the experimental films were shot on grainy, decomposing 16mm or Super 8 film, many were frenetically edited and the film was often painted on. The films shown at CineKink kept true to a traditionally mainstream, slick, high production porn look, complete with near perfect female bodies and lots of blonde hair. Yet, many of the filmmakers featured on Saturday share intellectual, professional and personal goals and ideologies. Like the women shown at PS1, Audacia Ray and Candida Royalle actively identify as feminist filmmakers; Candida Royalle was a founding member of Feminist for Free Expression and emphasized her strict ‘no cum shots’ policy, because she finds this standard adult film shot decidedly humiliating to women since it privileges the male actor’s pleasure over the female actor’s.

In a quote found on her website regarding her forays in sexually explicit filmmaking, Carolee Schneemann explains that when making Fuses she "wanted to see if the experience of what I saw would have any correspondence to what I felt — the intimacy of the lovemaking... And I wanted to put into that materiality of film the energies of the body, so that the film itself dissolves and recombines and is transparent and dense — as one feels during lovemaking." Thus, Schneemann’s impetus in making Fuses was a desire to represent her authentic, personal experience of female sexual pleasure — something absent from most representations of women’s sexuality in porn, where women often serve only as vehicles for male pleasure.

But when asked about the highlights of any of the fifteen feature length porn films she has directed or co-directed, Candida Royalle echoed Schneemann’s concerns, stating that her favorite portions are those that "tell a truth about my life, showcase sexual evolutions from my life and where I am deeply connected to the movie because it's personal." She went on to say that audiences have the most positive responses to scenes where the actors truly desire one another, because it "seems to be that people feel that full sincerity, the authenticity of the real connection." Royalle described her interest in fostering a positive sexual experience for the performers and audiences alike. Calling the sex in mainstream pornography "boring crap," she explained that she works hard "to pair actors together who have genuine chemistry… Women and couples want something different, something not typical of adult entertainment, something more imaginative, more creative;" something with a similar set of conceptual parameters as the films of Schneemann, Hammer and Rubin.

Though I recognize that many feminist artists and filmmakers would abhor acknowledging any connection to a misogynist adult entertainment industry, there are enough similarities between the two sets of filmmakers to warrant a comparison. Both camps are participating in the same social and representational conversation, even though they are also participating in two divergent cinematic conversations. Each set of women filmmakers is reacting to a similar drive to forge a new and unique language for depicting female sexuality on film in a feminist and sex-positive way. Women want to view material that gives them sexual pleasure and accurately depicts their sexual experiences, just as men do. The two sets of women simply chose different, and culturally oppositional, vernaculars for that expression. This divide between high and low culture is unnecessary, at best, and retrograde, at worst: each group would gain enormously from a dialogue and the sharing of resources.

Where porn directors have funding, a wide audience and distribution, they lack creative control. Candida Royalle repeatedly bemoaned the adult industries' attempts to squelch any avant-garde impulse in pornography and argued that the industry would change only when directors coming out of the experimental film genre began to make sexually explicit films. Where experimental filmmakers have complete creative control, they have small audiences, little funding and often no distribution. Though at times these circumstances are self-imposed, lack of distribution for experimental film is a tragedy when the films are as groundbreaking as the ones featured at PS1. The work of the experimental filmmakers could have a much greater effect on how popular culture deals with female sexuality if they were able to harness the established adult entertainment networks. Moreover, the lack of resources works to silence the voices of many experimental filmmakers: speaking in an interview in November 2007, Carolee Schneemann said that not only is she unable to support herself with her work, she is often unable to make work because of a lack of funding. Perhaps Candida Royalle could pick up and distribute Schneemann’s work through her new company whose aim is to launch the careers of new female pornography directors. If she were to offer, would Carolee Schneemann agree to be included in the pornography camp?

In order to productively engender a new tradition of female sexual expression, there must be women (and men) working within and without the existing framework of art and pornography to move the conversation forward. The women working and experimenting in the adult film industry are as critical to changing the tone of the cultural discourse as those creating radical experimental cinema, and both parties should be active parts of that exciting conversation. To deny the similarity of the goals is to promote a myopic, boring and tired exchange that only further promotes the idea of a pretentious art world separated from the culture at large. Art can and should affect popular culture’s representation of women. Furthermore, art intellectuals are as excited to see real sex on screen as anyone else. Art and pornography can both serve as positive vehicles of our desires, fantasies and imaginative capabilities and it behooves us to open the boundaries of either category in order to advance our aesthetic language and create something altogether new.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian