This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

Recently by Deborah Fisher

Matthew Ronay

Andrea Rosen Gallery - 525 W 24 St, New York NY

1 Februrary - 8 March 2008

Matthew Ronay is a good sculptor. He's not just making iconography in 3-D. He consistently tells a story about something larger than himself using our ideas about space and arranging objects to create interesting visual fields . I use Matthew Ronay's work when I am trying to explain the difference between a sculpture and an object to my students. He's definitely doing it right.

And when I teach really good students, I use Matthew Ronay's work to explain what happens when you do it a little too right, and do too little beyond that. His work tends to be very much of its sources. It's a little too Jessica Stockholder, and way too Paul McCarthy. It’s all blustery talk about getting fucked by big black men, all cock-and-balls, but cute cocks and balls. With a candy coated shell, downright conservative execution, and very little placed on the line. The note he tends to hit is hip and impersonal. The idea of a disaster.

Transgression Lite.

But there are no outwardly transgressions currently on view at Andrea Rosen. And very little MDF. No bright colors, "shocking" guttertalk titles, blood or buttholes. No grass or landscape or freeway. Nothing glossy, nothing cartoony, nothing silly, no scatology. Go to Andrea Rosen and see for yourself. There is sensitive primitivism devoid of schtick. Some rich material choices and an overwhelming sense of the artist's hand at work. It's still on the conservative side, but it's not cool. It's representations of shelter instead of speed. It's Africa meets Sukkot meets the feeling of being adrift at sea. It's romantic and it's earnest.

Liz Craft

Marianne Boesky Gallery - 509 W. 24th Street, New York NY

November 17 - December 22, 2007

I was introduced to Liz Craft's work in 2002, as a student in a graduate seminar, sitting at a conference table in a dark room, while a professor of mine was desperately trying to explain the importance of taking risks. She showed us a handful of shaky progress snapshots of this sculpture, which would become Death Rider (Virgo).

The viewing conditions were not ideal. The sculpture was half-shrouded in a blue tarp with tools and a gantry surrounding it, but it still blew my mind a little because it was totally cheesy and, more dangerously, palpably earnest (and yet I didn't hate it!). It took the bored, knowing head nod that contemporary artists are supposed to achieve and turned it inside out. Instead, this thing charged at my eyes and made my heart bulge against my shirt, because it was made with so much love. And it confused me because it was totally balls to the wall and, at the same time tame, traditional, and studded with cliches. It's a traditional bronze statue of a skeleton riding a motorcycle for chrissakes!

I decided in that moment that Liz Craft must be some sort of empathic genius.

The edge in Craft's work comes consistently from doing what artists should never, ever do. Instead of resisting artworld cliches like seventies stuff, unicorns, or what would become "Banks Violette Gothic," she charges into them. Instead of distancing herself from the language and materials of traditional sculpture, she depends upon them. Instead of relying on irony, she commits to a vision. The result is work that is fantastically fresh, but in no way "new." It's fresh because it's wrong; because it obviously delights in fights against art history and tradition, against cliche, against what sophisticated art viewers expect to see.

So it should not surprise you that I had expectations for this show that's currently up at Boesky. In fact, I thought I knew what I was going to write for this review before I even walked into the gallery. Instead, I am finding that I have to muddle through my hero worship to arrive at a place of opportunity. The show at Boesky is not very good; but at least it's not very good in ways that are meaningful to lovers of Liz Craft's tendency toward risk and helpful to risk-takers everywhere, who must know by now that it's no fun if you can't fail!

Craft's untitled show consists of large, medium, and small aluminum architectonic forms that are studded with windows, fireplaces, and other kinds of (mostly square) holes, which function to create inside and outside spaces. Inside these holes are cast interior spaces like flower vases or figures floating in water, also aluminum, welded to the larger architectonic forms. These are not mini-installations or assemblages. Everything is the same material and welded together, so each sculpture is a distinct spatial expression rather than a collection of relationships. Each piece is painted a supercool glossy white, and this emphasizes the tension between inside and outside. All of this makes the gallery, of course, into the largest of these container spaces; as time goes on you may well become aware that you, too, are inside a larger instance of these modeled spaces, the gallery enclosing you and the work in a Russian nesting-doll style configuration.

Don Quixote and Other Stories

Javier Piñón

15 November - 22 December 2007

ZieherSmith - 531 W. 25, New York NY

I like collage. It's fast and economical, and paradoxical. It's about making things up by not making anything up. And, like Javier Piñón, I am from the southwest. So I grew up on all this Marlboro Man imagery and the rodeo, as well as a heavy dose of Catholicism. I can't go on without admitting that Piñón's work soothes me — it confirms and upholds some things I already know to be true. It's easier to write complete and rigorous thoughts when you're pushing at something new.

But Don Quixote And Other Stories is not about novelty. In fact, in some ways you've seen this show before. It's all smallish and tastefully framed. It's doing that surrealist collage thing that Hannah Höch explored thoroughly about 80 years ago and is now downright academic. And it's steeped in all sorts of things you may or may not already know — it's about references. It helps if you've already experienced the visual language of the actual southwest: its sweet and desperate patron saint candles and lonely roadsides, and the technicolor landscapes of old Arizona Highways and Sunset magazines. It is helpful to walk into this show knowing your mythology, your western films, your pop culture. It also helps if you've read Joseph Campbell.

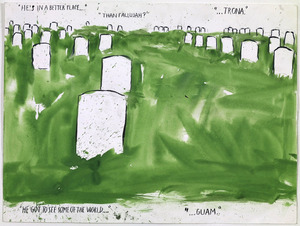

and gouache on paper, 18 x 24 inches.

Courtesy of David Zwirner.

Raymond Pettibon

David Zwirmer - 519 W. 19th St. New York, NY

11 September - 20 October 2007

Raymond Pettibon is one of the first artists I have ever loved and the only contemporary artist I have known about since high school. In the context of SST Records, he helped me arrange my first relationships to power. My own seething over Grenada. Iran-Contragate. Reaganomics. I don't care that Pettibon doesn't like to discuss that part of his career anymore — I can't think about him without vividly remembering the summer I spent watching Oliver North and Fawn Hall take the stand on C-Span in my friend Mark's crappy little studio apartment, my head shaved and finally a set of car keys in my pocket, a Black Flag album cover in my lap. My fists and jaw were probably clenched.

I love Raymond Pettibon because he understands the existential weight of having to take it all in. Everything from the comic-book format to the way his individual drawing refuses to turn into anything more than a scrap of inky paper confirms that he is not special, not a genius. He is just someone who watches the world, and the world makes him sad and mad and desperate. This sadness and desparation — punctuated by occasional glimmers of hope reflected in the lonely soul of the individual — is meaningful. And it's totally punk rock. Still. The message in Here's Your Irony Back (The Big Picture) is the same as the overwhelming lesson of the eighties, of Jello Biafra and Henry Rollins. You can see exactly what these fucks in power are doing. And you can do more than talk about it. You can scream your fucking head off about it. You can get really angry. You can put safety pins all over your face and your pants and you can dance powerfully and tribally about it until you are a drunken, soggy heap, and you will be beautiful and meaningful. You will, in that moment of total writhing expression, make perfect sense in relationship to the rest of the world.

Folks

Michael Cline

Daniel Reich Gallery - 537 W. 23rd St., New York NY

September 15 - October 20, 2007

Unknowing Man's Nature

Jules de Balincourt

Zach Feuer Gallery (LFL) - 530 W. 24th St., New York NY

September 6 - October 13, 2007

First, I want to applaud both Michael Cline and Jules de Balincourt because they are aiming at something grand, or at least larger than themselves. This represents a real risk that should be acknowledged! Art with content in Chelsea tends to be about defining the individual artist, rather like using your hobbies to define yourself on your Myspace page. Matthew Barney is perhaps the most extreme example of this self-involved bricolage. Barney’s interest in everything from tea ceremony to the Isle of Man becomes a small piece in his baroque self-myth, and this self-myth, or brand, is his intellectual project.

Instead of working exclusively in terms of defining themselves, both Cline and de Balincourt are working to understand the world we all share — they are facing out instead of in. It's hard to reach past the self in this culture, especially when there is so much freaking money at stake in Chelsea.

It's also hard, after getting your average MFA training, to envision how to effectively reach past yourself and engage more than your own backyard of personal interest; whether it's trashing hotel rooms in a coke-induced stupor, or something more wholesome like surfing. We can all be honest and admit that as MFA candidates we were taught to think of ourselves as very interesting people, but that in fact what is interesting right now is just how fucked up the world might be.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian