This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

Gas Masks, Israel & Human Rights: An Interview with Street Artist Mike Marcus

Last fall, I encountered odd black and white images of nude women donning gas masks around the Flickrstreams of my New York contacts and shortly thereafter started spotting them on the streets of lower Manhattan and northern Brooklyn. They seemed out of place in that they were absurd and seemed to have appeared on the streets of the city overnight.

I finally spotted the artist's name on the bottom of one piece in Bushwick written as Mike Marus, which I later discovered was actually Mike Marcus. The alienated figures are powerful and poignant and from someone who obviously had something to say, though at first I wasn't sure exactly what.

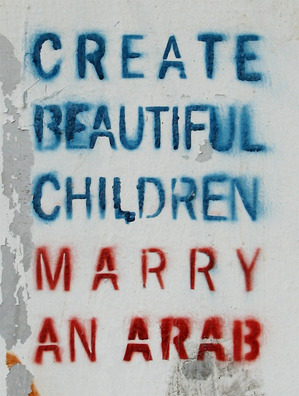

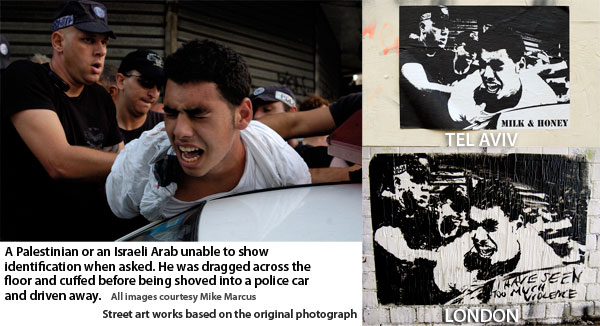

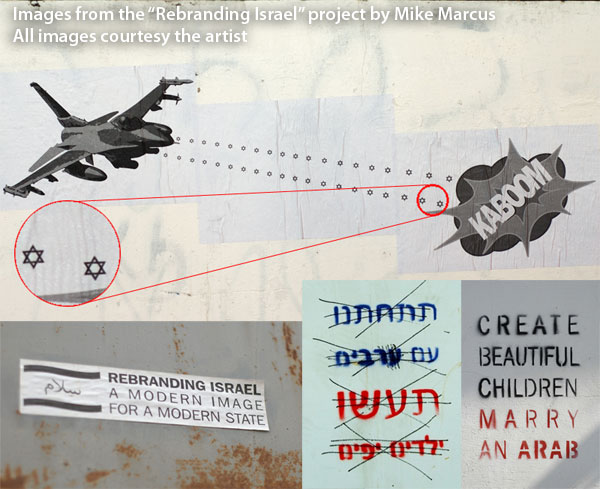

After a little digging I discovered that Marcus is a Brit of Jewish heritage who moved to Israel in 2000 and has since moved back to London. His confrontation with the realities of the Second Intifada and Israeli rights abuses against Palestinians galvanized his art. Filled with anger, he took his message to the street and started producing public unsanctioned work. His early work first focused on posting images of West Bank violence on the streets of Israel and then he shifted gears and began to incorporate more penetrating attacks at the essence of Zionism, namely, the purity of the Jewish people and the sanctity of Israel as an idea.

The Rebranding Israel project doesn't pull any punches and its brash imagery portrays a side of Israel many Zionists refuse to see. Marcus has also created a series of art works where he gassed himself with CS gas (tear gas) and photographed the results. As the artist points out on his blog the meaning of his self-gassing was related to his history as a Jew and the current ironies of the Palestinian/Israeli conflict (emphasis mine):

CS is the most common form of tear gas. Its use by military forces is forbidden under the Geneva Convention and the Chemical Weapons Convention of 1997. However during the first year of the Al-Aqsa intifada alone the Israeli Defense Forces used 120,000 tear gas grenades against Palestinians as a form of racially motivated collective punishment.Although the Jews own encounter with the gas chambers makes the use of chemical warfare notable for its irony, it is only one example of the many human rights abuses exercised by Israel during its 41 years of military occupation.

To encourage awareness of the continuing violations enacted by my people against a weak and vulnerable minority and to register my protest, as an ethnic Jew against the injustices carried out in my name, I exposed myself to CS gas and photographed the results.

I had no other way to cry.

Marcus seeks to burst the "bubble" that engulfs life in the great Jewish state and his recent street work continues the trend of pushing that envelope. Within this context we see the cloud of dread that hangs above his gas mask donning mannequins, seemingly caught unawares at the start of an apocalyptic new season. She looks like she we just stepped out of the Garden of Eden and she stands silently watching us eat an apple laced with some hazardous material.

About the mannequins, Marcus has this to say (via his blog):

She is all of us:Dirty and fatigued by a world which expects too much and doesn't give enough in return. Guilty because in a dark place she keeps the knowledge that society is no more than a collection of of her. There is nobody else to blame so in silence she stands and watches.

Hiding behind a mask of her own making she protects herself from what?

...

She fears this week's new collective anxiety. Islam? Terror? Dark skin? She can't remember the difference anymore.

Her bag is packed, back is covered but in the end she stands nude and accountable in a crumbling city.

Marcus describes this female figure as a metaphor for some sort of traumatized collective consciousness. There is an air of science fiction to his work, as if he is projecting his imagery into a bizarre future. Elsewhere on his blog meanwhile he makes a provocative statement about his work based on Israeli issues:

Its easy to provoke a reaction in Israel. All you need to do is tell the truth and watch everyone flip out.

Intrigued by his aggressive imagery, I spoke to Marcus online in an effort to understand his work.

HV: And when did you start creating street art?

MM: Maybe 4 or 5 years ago. I started actually with street interventions, not necessarily art, during the disengagement of Gaza. Israeli society was ideologically divided. Those who were against the disengagement put orange ribbons on their cars. As a response, the people who were pro-peace put blue ribbons on their cars. I went around swapping all the ribbons around and adding colors of my own.

HV: That sounds like culture jamming...what were people's reaction to that intervention?

MM: There was so much public reaction to the political situation that my actions were mostly lost in the noise. However a journalist friend of mine was particularly interested by the fact that I was an immigrant and was so ideologically active. He wrote an article which basically got me interested in the fact that I can make public interventions and they can have a widespread cultural effect.

HV: You are most famous for your image of a woman with a gas mask. I have to ask you, is she nude or wearing some kind of body suit?

MM: "She" is a mannequin, you say that I am most known for this but it is a location specific thing. Maybe in NYC and London that it true but in Tel Aviv I am known for gassing myself and the "Rebranding Israel" street art projects but you might not be aware of them because most of the articles were written in Hebrew.

HV: When I first saw the mannequin/gas mask image I didn't really know what to make of it. It was both absurd but beautiful. What were you trying to convey?

MM: When I moved to London I started putting stuff up on the street and realized that the rules were very different from Tel Aviv. I decided that I needed a project which would allow me to understand these new rules. I had recently taken this photograph, just for play really and decided that it would make a pretty iconic street image. I started off pasting it mainly to learn the rhythm of the street and as i put more and more up I started to realize (like is often the case) the subconscious dialogue which is conveyed by the project.

HV: What do you mean by "rules"? Are the rules the same in London & New York?

MM: I'm not sure of the rules of NYC, I was only there for a week and I had lots of help from various artists and aficionados while I was there. It seemed to me though that understanding the rhythm of the street in both London and Tel Aviv stood me in good stead for NYC.

I'm not sure that rules is the right word, I would say more "feel." There aren't actually any rules but the way which I approach the street in London and Tel Aviv is very different, it's about knowing what are acceptable actions and what will get you into trouble. I was arrested a couple of time when I first got here because I was acting as I would in a different city.

HV: After I learned more about your work via your blog I got a sense that the mannequin with gas mask image has a dark sensibility affiliated to violence, was that your intention?

MM: At first, I wasn't consciously aware of any direct intention. Sometimes the best project happen when you just let yourself flow with the current. For some reason I resisted analyzing the meaning of the work for months. It wasn't until I had over a thousand figures on the streets of London that I really started to think about what it was that I was actually trying to achieve.

I think that all my work is directly derived from the fact that I have seen too much violence and hatred. I went out actively seeking knowledge of the "situation" in the West Bank rather than hiding myself from it, like most Tel Avivians

HV: I know this isn't an easy question, since the answer is probably more complex than you could offer in a few sentences, but how did you confrontation with the realities of violence in the West Bank impact your life and perspective?

MM: Maybe in some way I instilled a small amount of post traumatic stress into this work. I needed to purge the shit I went through as an activist in Israel when i returned, I was very angry and I used street art as a sort of therapy. That's why I did this.

HV: So what are you thinking and feeling when you hear about the Israeli invasion in Gaza right now?

MM: I went to Israel with little knowledge of the reality, I was brought up by militant Zionists and although I rejected their teachings at an early age, I still didn't know the real history of the region. For some reason I couldn't just hide from it like most people. I started traveling to the West Bank regularly to see for myself what was going on. Then I started photographing it and pasting it on the streets of Tel Aviv because i believed that people had a duty not to ignore what was being carried out in their name. I started getting very deeply into activism as a result. It's difficult for me to listen to what is going on, I feel like a failure because I am unable to stop it.

It's always possible to pick olives with Palestinians and remove road blocks but in the end they're just small gestures. The Palestinians can't pass the roadblocks even once they are removed because they get shot if they are seen on an Israeli-only road.

HV: What has your experience taught you about the representation of violence? Are we all numb to it? Does anything shock people out of their complacency?

MM: I think that TV, Hollywood and computer game production companies are guilty of serving us violence as entertainment; I have seen people, when faced with real political violence, burst out crying because it never occurred to them that it could feel so real.

I can't see anything remotely entertaining about an Israeli activist getting shot in the head by an 18-year-old soldier from Tel Aviv because he was wearing a t-shirt with Arabic writing on it. It's simple hatred. That's what the entire Middle East situation is based on, state-sponsored racial hatred.

HV: What is the role of art in this state-sponsored hatred? Have Israeli street artists or others been critical of that?

MM: Not enough.

HV: Why do you think that is?

MM: Like all sections of Israeli society, street artists concern themselves with issues inside the "bubble" -- the way to cope (as I'm sure was the case for average German citizens in the 1930s) is by ignoring that which is too uncomfortable to look at directly. However the "situation" still fuels passions whether consciously or unconsciously and, as a result, the Tel Aviv street art scene is really rich.

HV: Is there any Palestinian street art?

MM: Yes, Banksy was an inspiration to many of the younger hipsters in Ramallah at Qalandia where he did some of his stuff on the wall. Many others have taken the cue and there are miles of stencils and sprayed messages. There has also always been a history of political graffiti and posters of "martyrs" on the streets of Palestinian cities but that's not really street art.

HV: Hipsters in Ramallah -- boy the world really is a global village, isn't it? By the way, when were you last in New York?

MM: I stayed in Williamsburg, and ventured all over (as much as was possible in a week) and on the last night, fell in love with the walls of Bushwick. I know people complain that Williamsburg has becoming over-gentrified but to me it seemed like a wonderfully inspirational environment.

HV: Well, New Yorkers like to constantly gripe about gentrification. But I noticed you did one incredible six foot high piece in Bushwick on Bogart Street. How does scale impact your work and the message of your imagery?

MM: I see the gas mask mannequin piece as an experimental project. It taught me a lot about working in cities much larger than Tel Aviv, where 100 A3 posters would be a huge impact on a city, in London and New York, you have to go bigger to get noticed above the noise. Over the past year, I have been working on various techniques for achieving this.

Mind you, saying that, I also love the fact that I have all these very small hidden paste-ups all over London. I was out this evening with a friend and as we walked from the pub to the station, I counted maybe 5 small figures staring back at me. She didn't notice a single one. I like the fact that you see one and then become turned on to it and notice them everywhere. This approach however takes time and I didn't have that in New York, so I went big.

HV: Who are your street art idols and influences?

MM: No idols. Influences vary wildly depending on the project which i am working on most influences come form a non-street art background: Vanessa Beecroft, Anthony Gormley, Chuck Close. Mark Quinn's cast of his own head in frozen blood has had a massive influence on my work, and particularly understanding that to influence people you have to give something of yourself.

HV: That's an interesting mix; and how fulfilling does street art feel? In other words, what do you get out of it?

MM: I connect on a deeper level to my urban environment but more importantly it forms a piece of a larger plan

HV: What's the plan?

MM: I am increasingly trying to integrate my fine art and street art careers.

HV: To what end?

MM: I have much to say about the world. My experience and positions is focused through the particular lens of my ethnicity, upbringing and life experiences. I believe it's a valuable message and I personally need to do my best to help solve the Palestine situation. The greater my cultural influence the stronger and louder my voice. This is my main drive. To develop cultural authority so that I can use it to make the world a bit better. I have the greatest respect for Banksy who has been very successful in this (although I don't care much for his art). Also Shepherd Fairey has started to use his influence for similar ends, like commentary on the war against Islam, the support of Obama, and so on.

HV: You mentioned your were raised by Zionists, so I'm assuming your ethnicity is Jewish?

MM: Ethnically Ashkenazi (the western Jews), religiously, a proud and well-balanced atheist.

HV: I know you've posted a photo of yourself on Flickr with the words "self-hating Jew." Have you ever been called this?

MM: Many times, mostly by Americans, sometimes by my own family or the community where I grew up.

HV: How do you react?

MM: No point reacting to a Zionist, since its adherents are convinced that they hold the secret key to truth.

HV: What is the one thing that you would like to achieve that would make your art and life's journey "worth it," in your opinion?

MM: I would like to have enough cultural influence to be able to convince a generation of Israeli kids to object to military service. I think that doing this would have an influence on an international scale.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian