This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

Who's afraid of Martha Rosler?

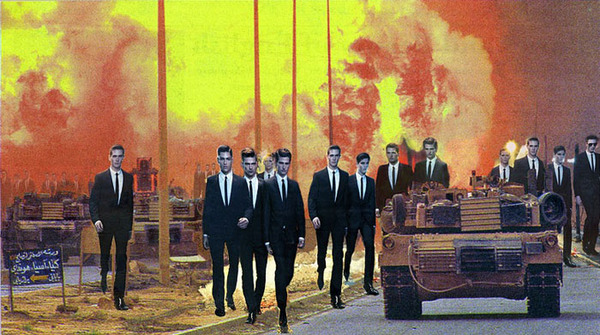

GREAT POWER

Martha Rosler

Mitchell Innes & Nash - 534 West 26th St, New York NY

6 September - 11 October 2008

There are a lot of things to dislike in Jerry Saltz' recent jeremiad against Martha Rosler's GREAT POWER in the pages of New York Magazine. First, and most embarrassing coming from a committed formalist like Saltz, is the casual mendacity of: "Four decades later, Rosler turns out not to have changed the look of her own work at all." Even granting that the "look" of Rosler's collages in GREAT POWER does not depart from her sixties-era series Bringing the war home… -- because, you know, that's entirely the point -- we are apparently expected to believe that the last time Saltz has had any exposure to Rosler's work was four decades ago. This simple impossibility, for a critic of Saltz' unique dedication, allows him to emit absurdities along the lines of "The only thing her work says is that fashion designers and women who like to shop caused two wars," before moving quickly past the art he was hired to review and onto more interesting topics.

It is not really my intention here to defend GREAT POWER, it is a difficult, and in many ways an unsatisfying presentation. I suspect this is the point. Regardless, what most certainly cannot be said about it is pretty much anything Saltz' says about it. It is not superficial. It is not a nostalgia trip. It is a pointed and examined deployment of representational strategy by an artist whose career is a noted catalog of such engagements; four decades worth, as it turns out. If it makes sense for anyone anywhere to pose the question of the relationship between the current political and cultural unpleasantness and the vintage variety, it is Rosler. Indeed, what is ultimately so depressing about Saltz' piece it that he is only too happy to miss the point entirely, making that rankest of amateur confusions: conflating his emotional response with his ultimate judgment -- it makes him mad, so it must suck.

But, to paraphrase, Saltz' review is simply stupid. What it points to however, is far more interesting and widespread. There are two passages in particular that I want to examine.

This is the first.

Clearly, there are parallels between the two wars, and activist art is valid. But Rosler lapses into simplistic nostalgia and undermines her older work while basically making pretty war porn.

And the second.

Anyone who thinks any of this is good art, effective activism, or even slightly radical needs to get a grip.

What is the relationship here between activism, radicalism, and good art? Saltz initially allows for the 'validity,' of 'activist art,' setting up, it would seem, the question he later begs quite explicitly: would it be possible for Rosler's work to be effective activism and bad art at the same time? It doesn't occur to the critic to formulate this question outright because he's too busy being aggressively bored, but it's an important consideration. Why does he have to discredit it both as activism and as art? Never mind the easily assumed authority in judging activist strategy! What Saltz seems to be engaging with, in his own resentful, teeth-gritting sort of way, is precisely that Brechtian legacy of which Rosler's career, at times more and less effectively so, is perhaps our clearest example. Brecht's fundamental contribution, it must be remembered, was not a specific piece of writing -- it is the rare artist, theatrical or otherwise, who can name more than three of his plays -– but rather an almost ontological subordination of art to politics. And, reciprocally, that persistently difficult claim, especially for critics, that all art ought to in some way deal with or approach political questions; that, in fact, the two cannot be separated. All art is political, there is only work which realizes this fact, and behaves accordingly, and that which doesn't and risks supporting the (unacceptable, naturally) status quo by its claims to being a-political. It's the old "you're either with us or against us" mentality; no doubt you've heard of it.

Whatever you think of this idea, it is certainly the case that it has so permeated contemporary artistic discourse that someone like Saltz, writing in a magazine like New York, feels uncomfortable simply stating his displeasure, for formal or conceptual reasons, with Rosler's show. He must also add, and rather sarcastically at that, that it's 'ineffective activism,' and only then can he proceed to say that it's also bad art. Saltz must either deny the validity of the Brechtian paradigm, and separate the political and the artistic value of the work, or send the politics down with the ship.

What really strikes me, though, is just how ill-served by this paradigm is not only the art, but the politics too. Listen to Saltz on Rosler's binder of newspaper clippings:

Rosler also includes news clippings about Iraq. Most of the articles are from reliably liberal sources (The Village Voice, The Nation, The New Yorker, etc.), so Rosler is merely filtering the already filtered. Worse, there's an air of self-serving, pedantic preaching.

Is Saltz a rightist? What is his objection here exactly? Surely he would not deny the positive impact of these 'reliably liberal' publications on the national discourse, so why the naked contempt for them in the gallery space? Never mind the centrist and further right Wall Street Journal and Economist clippings that also make part of the archive. What Saltz feels, but is prevented from saying, is that political art is not good art. This is a feeling that I suspect is shared by good number of people, who no doubt go to great lengths to justify this feeling as it appears in different contexts, though greater contortions than the ones on display here are difficult to imagine. What's relevant is that by being unable to simply state this, to simply separate art and politics for the purposes of a critique, Saltz fails in both directions. He passes judgment where he has no authority, in terms of the work's activist efficacy, and he proves utterly incapable of considering Great Power with a modicum of responsibility towards the actual, formal qualities of the work itself, its position within Rosler's oeuvre, or towards the artist herself, who, at this point it can be said without question, deserves better.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian