This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

The Russian Soldier

Men in uniform touch a deep nerve in Russia. The Soviet history of heavy internal policing has certainly left behind a symbolic residue on the personal dress code of state power. This sensitivity plays out across a spectrum of current shows in Chelsea that engage with soviet history and contemporary Russia.

Russia's appeal as a timely subject for contemporary art production is driven by more fundamental factors than the recent conflict in Georgia and its contested origins. Flush with black gold, Russia's rich can afford to outbid older money on the auction block; art dealers are clamoring to tap this lucrative market by introducing edgier contemporary art that evokes this country's past and future.

What unifies these different works together is the spirit of art as critique. Each work seeks to indict the culture that lends the uniform its menacing power.

A chilling portrait of young Russian cadets by Michal Chelbin is currently on view at the Andrea Meislin Gallery. Their unconfident and awkward poses betray their adolescence and insecurity. Looking tough involves much more than pursed lips and their eyes glaze over like a deer in headlights. The black uniforms contrast sharply with the aspen's amber leaves, white speckled trunks, and dancing patches of sunlight; it looks as if they are wearing black holes. This picture invokes an inherent insecurity for which many soldiers seek to compensate with their uniform.

But insecure boys can do still do terrible things. Josef Koudelka's photographs at the Aperture Art Foundation document in gory detail the pandemonium unleashed in the streets of Prague by the Warsaw Pact: the 1968 Soviet invasion following the Prague Spring. Bewilderment and uncertainty about the future are written across the bohemians' faces, while the soldiers meanwhile look more weary than brazen. Far from their families, worked like mules, and subjected to poor living conditions, the soldiers' destiny is bleak and unpredictable. That old narrative of triumphant conqueror and the defeated village is overridden by a collective suffering in which the choice of roles is a game of pick your poison.

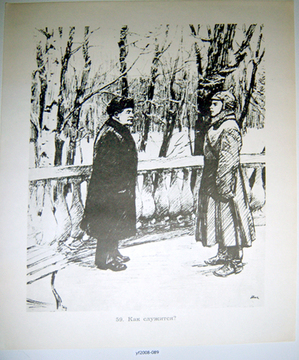

Such soldiers were fooled by Soviet propaganda that convinced them of their role's valiance. Among the many pieces of Leninist paraphernalia that Yevgeniy Fiks purchased on eBay and put on view at the Winkleman gallery, there is a striking illustration of Lenin face-to-face with a solider on a cold winter day. The soldier stands slightly taller than Lenin and salutes his sagacious leader as both endure the Russian winter. There is a clear division between the head that thinks and the hand that enforces, which both find mutually comforting despite the cold.

A strange nostalgia for this time in which a patrician Lenin did all the thinking for you is driving sales of such paraphernalia on eBay; a deep irony considering that this leader loathed the commodity. Viewers are invited to pick a work from the show and "adopt it." They agree to pay nothing to the gallery, and take the object home after the show's conclusion. The only condition is that viewers agree to never sell the object or seek to derive profit from its ownership in any other manner. It's an ironically Leninist gesture. The enforceability for such ideological arrangements begs deeper questions about this dark chapter in history. The show counters how the old communist regime of symbols, recently dispossessed from old meaning and accompanying ideology, is the latest target for art's program of privatization.

Jumping into the present moment, Alexey Kalima paintings at the Lehmann Maupin gallery critique what some describe as the current Russian police state. Whereas photography's perceived veracity documents penetrating truths, paintings can more poignantly illustrate dangerous fictions to which we nevertheless cling. Such fantasies would just look goofy as photographs and distract from the point.

By casting the Russian soldiers as Power Ranger figures in his works, Kalima targets the narrative of the superhero that boys embrace in the form of action figures, video game characters and military men. So many men cling to the uniform in order to taste power. Kalima paints with a limited palette of reds and grays and renders crisp lines and intense shadows. His style recalls an old comic book, which reinforces his subject matter on the visual level.

Kalima once remarked that "boys who grow up during a war, surrounded by war heroics – that's one type of boy. But now we have completely different types of boys – they only play at war on their computers. And thank god they expel their aggression there and don't run around with pistols. It's the same with military men – they need to do be put behind computers and allowed to do battle there."

Let's not forget that the damage done to others in the name of the consolidation of power. An installation in back of the gallery flickers between normal light and black light. The violet rays transform blank walls under white light into a wide mural of Chechnyans who conceal their identity out of fear of retaliation. They disappear before you can concentrate too deeply on their expressions.

Russian and Soviet soldiers are not monoliths and these works reveal the complexities behind their political role. The fables fed to young men are seductive, whether it is the leader that thinks for you or the potential to wield the power of an imagined video game hero. The obligatory angst of adolescence can leave boys susceptible to such appeals. Under the fog of war or political power, these promises are more hollow than comforting. Such contradictions between self-definition and lived experience would drive anyone to crave the clarity of brute force.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian