This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

Steve DeFrank in Interview

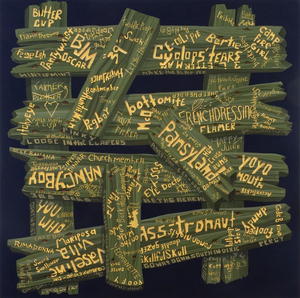

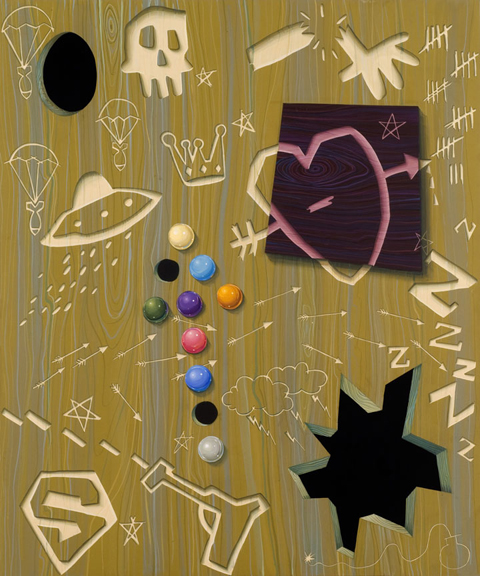

Steve DeFrank's new series of paintings in the exhibition Mirror, Mirror at Margaret Thatcher Projects plumb the depths of personal myth to reveal deceptively cheerful and malevolent emotions. His paintings depict a saccharine sweet caricatured naturalism rendering images of hidden sexual desire represented by images of degradation such as tree stumps and wooden boards riddled with carvings of phrases such as "Aunt Fancy" and "I Love Cum". The paintings are playful, but in a mischievous and subversive way and offer a significant departure for Defrank who had developed a signature body of work based on the format of the lite-brite toy. Steve and I had the opportunity to speak about his work shortly after the exhibition opened.

Andrew Cornell Robinson: You made a transition in your work. You moved away from your signature lite-brite compositions and created this incredibly series of paintings. Tell me about what was going on as you were going through this transition.

Steve DeFrank: I was doing the lite-brites, they were my gimmick, my shtick. It was beautiful, it gave me many gifts, and what I'd like to say is that my medicine finally kicked in.

ACR: You studied painting...

SD: I was trained as an academic painter. And that's what happened with the lite-brites. I studied at the Maryland Institute College of Art and then the School of Visual Arts.

ACR: I did too.

SD: You did not!

ACR: Did you have to draw those fucking plaster casts from the Parthenon at Maryland?

SD: Oh my god, yes!

ACR: When I was looking at your recent work I was struck by the attention to craft. And I don't mean that in a negative sense at all.

SD: I don't take it as that. In fact the lite-brites were doing the same thing. I was tinting my own lite-brite pins, and dotting those I's and crossing those T's. Craft is the same exact itch, it's just that the lite-brites became a gimmick, and there was no room left to grow after some time.

ACR: So you went through this radical change as an artist, and you did this in public. That must have been difficult. Think of all the flack that some one like Phillip Guston got when he made a radical shift from abstraction to painting objects and figures late in his life.

SD: No one today wants to look at his old stuff, because the later stuff is so great.

ACR: So what's that like for you? To move away from the Lite-Brites and build this new vocabulary in these paintings?)

SD: It was scary as all shit! I was in the studio working on making new lite-brites for a show, and I realized: "I can't do this any more." I remember calling up the gallery and I was like "I gotta cancel my show."

ACR: And what did they say?

SD: They paused, and then said, "what's going on, we've got to make a studio visit." They rallied around me, and were like, "lets just get through this one show." I told them that I couldn't see myself doing this any more, that I didn't see the purpose. Going to my studio was like punching a time card. I was doing work and it was soulless. With the lite-brites the excitement of learning how to climb that mountain was fun, working out the light, color and transitions - for a time.

ACR: Like George Seurat, the mathematics of color and perception.

SD: Yeah that took me just so far. It's interesting, every lite-brite started out as a painting. I would use the computer to translate the painting into a map of color. In fact any of the new work could be a lite-brite, but I couldn't get the attention to detail, the hair, the words...

ACR: Well there is also the light. You can see the connection between the lite-brites and the sense of light in the current paintings. It reads clearly.

SD: I love hearing that. One of the limitations of the lite-brites is that I couldn't have done any of those words, nor the hair. One of the things that casein does is it absorbs light. And they sort of emanate light as they absorb it, so you get this sense that these things. I found myself in a nice little cul-de-sac with the earlier work. There wasn't a lot of room to push the work. I had to really ask myself: "what do I love?" I've had a real love hate relationship with paint.

ACR: Why?

SD: Because of my training. When I realized I could render something, the big question became in my mind, "so what?"

ACR: Oh that reminds me of another Maryland Institute alumni; Donald Baechler. He was speaking at SVA several years ago, and he talked about having had this rigorous academic art education. And basically he came out of it having to unlearn everything, that he had to learn how to draw again. This was what it meant ot find his own voice. That is also what led him to acquire other people's drawings and incorporate them into his earlier work. To me it's interesting that you would go through one rigorous process and then move to yet another rigorous medium. I mean casein is really difficult to work with.

SD: Oh Andrew, it's in my DNA.

ACR: What does that mean?

SD: It's like being queer, I just am. I am geared to a certain way of working. It is laborious, painstaking. Some times I look around at other artists and I can be green with envy, coveting the simplicity of their work.

ACR: Oh honey, the environment we're in, in New York, in the art world it's very much like that. We're all pitted against each other....

SD: I know and that is so fucked up.

ACR: I know we're looking over each others shoulders, and judging each other and ourselves.

SD: Its funny, my students often say, "I worked really hard" and my response is typically, well uh, the art world doesn't really care. And frankly you're supposed to work hard.

ACR: But I want credit.

SD: (Laughter) Yeah, I know. But in the end this all comes down to the work I am drawn to making.

ACR: Tell me about the work that you are drawn to.

SD: Well there's Robert Gober for one. He has this sense of detail, and yet he always shows his hand. I mean he can paint a plaster cast of rat poison. Its perfect and then you realize... he's got a hand, and it's not an exacting hand. It's odd, abnormal.

ACR: Queer?

SD: For sure.

ACR: Why do you think that is so important when you look at his work?

SD: What it is, is sort of a... so much of the art world is, well some times you look at shows and its hands off, it's professionally done. I mean Bob, well, he's a professional. But he's also there as an artist, his hand is in the work and it's potent.

ACR: Especially when you think about other artists who show or hide their hand. For example, Julian Schnabel is an artist of the former category. His work is romantic, heroic in a way: an expressive hand. What's interesting about Gober is that he takes something that is seemingly normal, but perverts it slightly; he forces us to see it with a queer gaze. Whereas Schnabel's work is operatic, almost overwhelming emotionally, Gober's is unnerving. Gober whispers ghost stories into your ear.

SD: The universe that we artists create needs to feel complete. Artists like Peter Halley or Matthew Barney, for example, have work that is tight, complete -- and they know their world, their visual vocabulary. While I respect it I don't go there to renew my own work. I had to find my own voice. Teaching has helped me to slow down, and to look, and not be so dismissive. For the first time in my life, I feel like I am doing my work.

ACR:When I first walked into your studio I thought, "oh shit he's doing something here"; especially when I saw that panel with "I love cum!" meticulously painted into the scene. Oh my god! (laughter).

SD: You know that painting scared the shit out of me when I was making it.

ACR: Well tell me about that.

SD: I did a huge painting, it had all these tree stumps, and then I was like, let's just do one tree stump. And I was asking myself what world do I live in? And if it's my forest, then what history is going to be written on this tree for a million other people to read a million years from now, and I just thought, "I love cum!" (Laughter)

ACR: In my forest. in the rambles of central park and the Fire Island Meat Rack: I love cum. That's great. (Laughter).

SD: And it seemed scary to write that.

ACR: Why?

SD: It just seemed crude, silly, sophomoric. Yet not only is it true, but everyone's going to read it. My mom's going to read it, my students are going to read it, and well, here I am. But it's funny because so many people at the opening came up to me after having looked at that painting and were like "ooh, me too."

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian