This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

The Cruelest Month: On the Dangers of Mixing Memory with Desire

Actuellement : Regard Sur Mai 68: Photos, Musiques Et Voix

Alain Quemper

Dorothy's Gallery - 27 Rue Keller, Paris

11 April - 2 June 2008

The specter of May 1968 has been haunting us for forty years now, and it is time to put it to rest. This does not mean surrender, either to the rightist vision of a capitalism both benevolent and triumphant or to the reformist project of accommodation. Rather, it requires seeing this last gasp of revolution in the West for what it was: a failure as colossal in its implications as it was glorious in execution. "Those who make revolution halfway only dig their own graves," said the graffiti of the time, quoting Saint-Just. We — today's radicals — risk being buried alive in the grave May has dug for us.

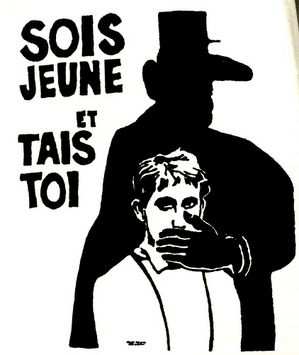

For it was in fact a failure on many fronts. Not just in the obvious sense — the ensuing return of normalcy and a rightward electoral shift almost unprecedented in French history — but also in its successive reincarnations as a banner of the revolutionary left. The fact that May became a spectacularized image, a simulacrum, represents perhaps the greatest betrayal of its politics. Indeed, this is a central warning of Debord's Society of the Spectacle: the ideological image of the proletariat creates Bolshevism, while the ideological image of the revolutionary moment, the anarcho-syndicalist fantasy of the day of the general strike, cripples the capacity for real action. The fetishization of May does the anarchists one better. Rather than placing the magical moment of revolt in an always near but never achievable future, it relegates it to the dead and irretrievable time of the past. This facilitates the production and marketing of glossy, red-tinted souvenirs — from the works of Badiou to The Dreamers and the myriad wistful think-pieces in the left-wing dailies.

In fact, as « Regard sur mai 1968 » at Dorothy's Gallery in Paris suggests, there was never quite as total of a revolt as some imagine. The show exhibits a hundred (quite unremarkable) 1968 photographs by Alain Quemper. Of these, perhaps half a dozen depict the flag-waving revolutionary protesters we are used to seeing (and even these contain a fair number of bored or vaguely interested bystanders). Another dozen show scowling apparatchiks like Pompidou, angry at the unrest. But the rest — the overwhelming majority — show the smiling and content faces of the culture industry: actors, singers, athletes. They look as unruffled as they do in any other year; as students and workers made lofty speeches, the capitalist apparatus they represented continued blithely to chug on. In short, though the French government was briefly in danger, neither capitalism nor the State itself had anything to fear — it was a replay, not of 1789, but of 1830.

The riots of May did manage to wring some concessions from the Establishment: a higher minimum wage, gestures in the direction of school reform, eventually yet another week of paid vacation. But these gains, the essence of meliorist reformism, have only helped to prostitute the really revolutionary aspects of the event. It is invoked in every demonstration in favor of the mainstream left, every squabble for a piece of the welfare state — a slap in the face to the workers and students who refused to settle for the possible. If the fetishization of May had had any redeeming qualities, these have now been thoroughly debased, made as ridiculous as the Bolsheviks' sentimental appeals to October 1917.

All this is not to say that May was worthy of contempt. It was, without a doubt, a heroic and beautiful moment. And it helped to eradicate the credibility of institutionalized Marxism-Leninism, one of the left's most stubborn demons. It transformed political and philosophical thought, and the Situationists' trenchant analyses remain as powerful as ever, despite the collapse of their program. But in order to transcend it, and to realize its possibilities, it is necessary to understand what its defeat means for any future radical politics.

I think it means nothing less than the end of strategic political action against capitalism; not simply the impossibility of revolution, but the unconditional and for the near future final victory of capitalism and the State. May was our best chance — a union of the old proletariat and the students, in one of the West's most developed countries, in a world boiling over with counterculture and revolt — and it failed utterly. Does swallowing the bitter pill of this defeat imply that there is no choice left but to compromise? It does not. If radical action is to be possible at all, it must involve the wilful rejection of strategy in favor of tactics. The world of the political must be conceded as the creation and the eminent domain of the capitalist State. (For it is clear that radical action which eschews revolution but not politics is unavoidably reformist, held hostage by the parameters of the system within which it operates.)

It is enough simply to look at subsequent attempts at political engagement with capitalism. The Weather Underground, the Red Army Faction, and the Red Brigades were a romantic Jesse James fable with a predictable ending. ("Keep your mouth shut until you have changed something," Ulrike Meinhof was supposed to have suggested — fortunately for the paper tigers of '68, it was a prescription that went unheard.) The anti-globalization movement is a classic example of the kind of coalition that would devolve into fratricide as soon as it gained any measure of real power, a development which is admittedly improbable as long as its activities are limited to waving Free Mumia signs in Seattle, lightly inconveniencing G-8 bureaucrats, and complaining about agents provocateurs in anarchist costumes. The difference between the provocateurs and the anarchists, in this case, is that the latter no longer have the heart for serious property damage.

The most effective opposition to capitalism in recent years has come from Islamic fundamentalists. Leaving aside the unpalatable implications of a defeat of capitalism in this context, it is important to note that the supposed strength of al-Qaeda in this struggle is almost entirely a myth cooked up by the Bush administration. Moreover, its avowed goal of creating a global caliphate, as well as its willingness to rely on worldwide flows of wealth, suggests that it is not incompatible with a more repressive and authoritarian form of state capitalism. The conclusion is inescapable: no alternative has yet emerged, nor is likely to emerge, that has the potential to challenge and defeat power on the political level. And if we take into account the insights offered by the soixante-huitard Foucault about the inescapability and the inevitable re-emergence of power, the political horizons that opened in 1968 look narrower still.

Yet, to the extent that something radical did happen in May, and in the Sixties as a whole, it was the attempt at creating ways of living together that could somehow defend themselves against the incursions of this system. The fact that they had Utopia in their sights, of course, made them impossible to sustain amidst the stubbornness of capital. But May was only one such attempt. History is rich in desperate renunciations, solitary critiques, communal withdrawals. These tactics, not solely drawn from the annals of anti-capitalist or anti-statist struggle, provide — and have already provided — a model for radicals in the world after May. Though it may be a model that owes more to hippies than to New Leftists, to Fourier than to Robespierre, its potential is more revolutionary and more universal. The tactics of the nomad kept ancient Scythia free from the Persians; ceding the scorched earth of the political in favor of an unyielding retreat is still the only way to check the Empire.

There is another reason not to maintain May's half-revolution as a radical fetish. Quemper says in his accompanying interview that digging up these photos was, more than anything else, a way of reliving his youth. May is the property of the Baby Boomers, both in France and in the United States; and it is therefore difficult to separate the real significance, the revolutionary quality, of the events from their role as the signifiers of a Vaseline-tinted nostalgia. The radicals of the future, it would seem, deserve better than this devotion to May as some transcendental and non-negotiable reference point. To bury it would be, if nothing else, a blow in defense of the new.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian