This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

Off the Grid: Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe at Alexander Gray Gallery

i've nothing to lose

nothing to gain

i'll kiss you in the rain

--from Blackout, David Bowie

Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe

Alexander Gray Gallery - 526 West 26th Street #1019, New York NY

April 30 - June 14, 2008

At the reception for Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe's transcendent show at Alexander Gray one of the guests kept prattling on about somebody they knew who knew David Bowie. Y'know, the typical overhear-me-please stuff that one sometimes hears at openings. But it was OK, because their random noise sent me in an appropriate direction: West Berlin, 1976.

Let me explain. I was climbing into the painting, Up, and thinking about all the ways it explores and exploits The Grid when my jabbering pals put The Thin White Duke into my head. In '76, when Bowie needed to get off the grid of a certain approach to song (and career) he went to West Berlin with Brian Eno to record two great albums, Low and "Heroes". The time signatures and melodies are never exactly where they should be, but somehow Bowie's escape from the grid makes the listener even more aware of it, not unlike the the Krautrock from which Bowie and Eno stole so liberally.

But I deviate. Obviously.

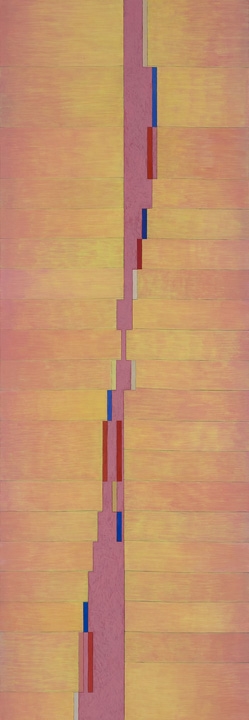

Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe plays the grid in a slightly different way. He exposes it right up front. However, the closer the viewer gets to the paintings the more obvious it becomes that the grid has been betrayed. Like the Berlin songs it's just enough of a betrayal to make us aware of it, but by then it's too late. We're in. It's not so much that Gilbert-Rolfe is challenging the viewer as he's inviting us to conspire in an open secret. A very beautiful and engaging open secret.

The more time one spends with the long home of these paintings the more they open up. Of all the songs from the Berlin albums, the instrumental Warsawza is the one of which I'm reminded most by this series of paintings. It takes an entire 7 minutes (an eternity for non-prog pop music at the time) to slowly unfold itself. In the aforementioned painting, Up, I remember staring at the painting for a long time before realizing that the horizontal line of the painting curves slightly up towards the center. In other works the lines provided by the painter aren't quite on, the vertical lines not exactly matching up with the comfort of the paintings' own internal grids.

Color and stroke are what hold it all together. "Heroes"' secret weapon was inventive guitarist, Robert Fripp. In an interview with The Orb's Alex Paterson he referred to Fripp as the most vertical player he had ever worked with. When pushed to explain, Paterson said that he would set the horizontal course for a song and then watch as Fripp discovered vertical planes Paterson hadn't thought of on which to place his guitar lines. On "Heroes" the listener can hear the same thing. The songs crash forward with the composed melody and complicated rhythms while Fripp's guitar seemingly plays against both things, counter melodies that stop short or speed past their expected resting place.

Color and stroke are what hold it all together. The dominant line in Gilbert-Rolfes' paintings is one of verticality, but things are constantly moving from side-to-side, to the edge from the middle, and then back again. The painter finds a common ground for a dialogue between colors that can be harmonious or adversarial and often both. Sometimes these colors are neighbors on the grid and sometimes they're layered atop one another on the surface of the linen. The strokes that led to the application of color might be tight or loose, creating a deep and rich field for the viewer to devour. Somehow all this action doesn't create anything frenetic or overwhelming. Everything comes together in the space between the surface of the paintings and the viewer, subtly opening new possibilities for the grid.

These aren't paintings as much as they are ladders into a Navajo prayer honoring the five directions: North, South, East, West, and the Center. With all the tugging and pulling contained in the confines of the four corners of these works, there is a sacred nature to their internal struggle. There is unity. They are a reminder of the past and of possibility. They are a kiss in the rain. The center — pushed, pulled, and prodded — holds tight.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian