This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

A.R. Penck at the Musee d'Art moderne

A. R. Penck

Musee d'Art moderne de la Ville de Paris

14 February – 11 May 2008

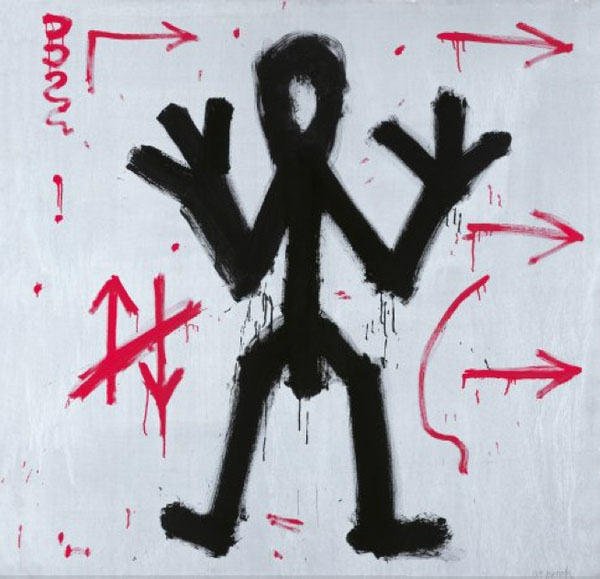

Ralf Winkler took his pseudonym, A. R. Penck, from the early twentieth-century geologist Albrecht Penck, an expert on the Ice Age. It was not an accidental choice: geology and "stored information," the artist says, have a certain affinity — and information is one of his most fundamental preoccupations. Penck is as much cyberneticist as painter. An elaborately conceived symbolic alphabet appears both directly and allegorically throughout his work, and his artistic project is constantly informed by the need to work through the implications of language, symbolic systems, communicative abstraction (thus, until the late '70s, Penck often accompanied his projects with theoretical texts).

Yet despite this very modern awareness of systems theory, his work consistently recalls the Ice Age in another way. Penck's artworks are not just vaguely primitivist: they are self-conscious evocations of the most ancient art. Penck sees his project as a "recourse to archeology," as "clearing a path through all of art history back to the cave paintings." This dialectical confrontation between the old and the new gives his painting a compelling, and unusual, pathos. The French sociologist Edgar Morin once described civilization as a passage from the problem of the caveman to the problem of the caves within man. Penck aims to attack both problems at once.

Penck's mid-'70s paintings, under a number of new pseudonyms (Mike Hammer, "TM"), show a retreat from this kind of abstraction towards a more explicit engagement with theory. 1973's Standart-Theorie, Standart-Technik, for instance, constructs an apparently dialectical hierarchy: "Theorie I" includes various historical concepts like "Weltkrieg," "Technologie," and so on; "Theorie II" includes sundry psychoanalytic terms like "Sensualismus" and "Totem"; and the two are presumably transcended by a synthetic, and unelaborated, "Standart-Theorie." While these paintings are intellectually thought-provoking, they rely heavily on word-collage and conventional techniques of abstraction, which dilutes their effect. Penck is at his best when he realizes the full potential of his "recourse to archeology" — the immediacy and embodiedness of his cave paintings combined with theoretical sophistication.

Unfortunately, in the last three decades, he has largely avoided this style in favor of sprawling, dimly neo-primitivist abstract canvases, many having to do with the Germanies' tribulations before the fall of the Berlin Wall. These are not quite as powerful as, for instance, his old comrade Jörg Immendorff's Cafe Deutschland series. One, however, stands out from the rest: 1995's Theoretiker und Löwe (Hieronimus modern). The lion that dominates the right half of the canvas evokes the animal scenes of Lascaux; yet, unlike Lascaux, the human figure is not elided. The painting draws a thread through time, from the prehistoric shaman's encounters with malevolent spirits, to the Christian legend of St. Jerome and the lion, to the contemporary radical theoretician's struggle with the looming and faceless incarnation of power. Yet the essence of this eternal confrontation remains inaccessible: it is both atavistic and unassimilably modern, both arcane and abstract. Such is the paradox that underlies Penck's art.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian