This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

Kori Newkirk at the Studio Museum

Kori Newkirk: 1997 - 2007

The Studio Museum in Harlem - 144 W. 125 St, New York NY

14 November - 9 March 2008

At Kori Newkirk's retrospective at the Studio Museum in Harlem, there is a clever neon sign installed. It reads "TAKE WHAT YOU CAN."

Newkirk is keenly aware that "YOU" will deeply shape how you approach his work. Beyond the individual subjectivity of each viewer, it is a plain fact that black art intrinsically means something very different to the African Diaspora than it does to any other group. To approach any work that hangs at the Studio Museum in Harlem is to enter into the land of double meanings. Your commentator is certainly not going to claim the transcendent authority to see this art through both black and white eyes, or alternatively that it can be viewed in a color blind manner. The very act of visiting Harlem and walking through the Studio Museum's door engages the viewer in the ongoing question of race and how art explores it. To pretend otherwise would run the dangerous risk of decontextualizing the work. Newkirk tells the viewer to take what you can, knowing that everyone will take away something different.

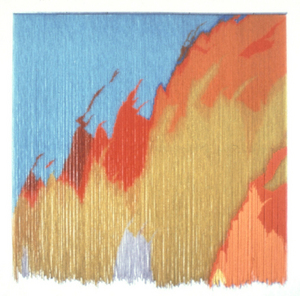

The work is not, however, just a generic image of fire. Beneath this stunning representation, there is an image of tragedy: Newkirk seeks to invoke the fires of the 90s race riots in Los Angeles. The fact that this might not be immediately apparent when looking at the work is crucial. It emphasizes the extent to which dark episodes in the history of American racism have not been encoded into mainstream history.

In other bead curtains installed in the hall, Newkirk also harnesses the inherent pointillism of a technique of tightly aligning rows and columns of pony beads. For example one recent curtain depicts the skyline of New York with the Brooklyn Bridge in view. In this image the space between beads reads like fog over the water. The blocky composition of the half illuminated buildings and water created by the beads also appears like a heavily pixilated digital image. On the formal level, such play with focus and sharpness may have been pioneered by Richter in his fuzzy photograph series, but there is a deeper reason why Newkirk wishes to obscure this iconic view of New York’s skyline.

The buildings are half illuminated because janitors are working at cleaning them. The invisibility of this largely black workforce is captured by only showing how their work illuminates these spaces. The bead's luminosity captures this effect marvelously. One mostly white and ruling class inhabits these buildings by day while another mostly black and working class inhabits them by night. Does such a site of racial inequity deserve the iconic glamour of the New York skyline? The pixilation produced by the beads subtly denies of this traditional upward gaze upon New York skyscrapers.

The second video – Bixel from 2007 – features Newkirk, almost entirely naked, gallivanting through a prairie. The prancing Newkirk stumbles upon a stash of silver glitterly ooze and begins to consume it, which then induces him to dance more feverishly. As in Titan, Newkirk plays with the idea of a substance entering and affecting the body. The verdant and idyllic landscape reinforces the scene's euphoria.

It is unusual that no major review for this retrospective addresses the narcotic content of these pieces. The subject seems unavoidable given the medical connotation I.V. stand and the effect of the silver glitter on Newkirk's dancing. At the risk of offending politically correct sensibilities, there is a problematic historical narrative of drugs and black culture. In a highly racist capitalist system that restricts African Americans and other groups to the bottom of the socio-economic ladder, drugs in the American exchange economy represent a way for the historically underserved to accumulate wealth and power. The euphoria offered by drugs also offers a source of joy in a world that bombards its subjugated people with bitter episodes of violence and discrimination. The works beg the question of these paradoxical relationships rather than offering a judgment or proposing a solution.

Obviously, a black drug dealer and a white client might interpret this work differently. Adrian Piper perhaps drew the clearest distinction between the black and white gazes onto art works created by African Diaspora and presented in that context. Discussing her own work in a 1992 exhibition at the Herron Gallery of Purdue University, she drew the following distinction:

"…. the work functions differently depending upon the composition of the audience. For a white viewer, it often has a didactic function. It communicates information and experiences that are new, or that challenge preconceptions about oneself and one's relation to blacks. For a black viewer, the work often has an affirmative or cathartic function: it expresses shared emotions or pride, rage, impatience, defiance, hope that remind us of the values and experiences we share in common. However, different respond in different and unpredictable ways that cut across racial and ethnic boundaries."

An understanding of the different baggage with which varying identity groups interpret contemporary art has sometime been missing from criticism and reflection on Newkirk’s work. Instead, much recent discourse has gravitated toward the term "Post-Black." Like all the other post- neologisms, the aim is first and foremost to emphasize a negation of past precedents. The main point was to move past the explicit iconographic paradigms of documenting racial injustice or imitating African styles that characterized the black aesthetic enterprise after World War 2. This term "Post-Black" was borne during discussions of the 2001 Freestyle at the Studio Museum. It's inherent ambiguity has generated a lot of debate, perhaps partly because it could be misconstrued to denote that authors attempting to deny the blackness of the adjective's subject.

This concept of Freestyle is a positive rather than negative term with which one can understand recent black art. One views the past cannon like a DJ taking items of aesthetic interest and juxtaposing them to create new and intriguing content. Meaning is not fixed but fluid and open to individual interpretation that is bound to differ between racial experience and a host of other factors. While the work still engages with black issues, it does so in a more opened ended, playful and less ideological manner. The goal is to provoke stimulation without directing the viewer to a specific intellectual destination. TAKE WHAT YOU CAN is truly the best mantra for this moment.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian