This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

TV Nostalgia

Television Delivers People

Whitney Museum of American Art - 945 Madison Ave New York, NY

12 December 2007 - 17 February 2008

You can tell a lot about a video exhibition by how the videos are shown. Those square grey cushions let you know to move on quickly while couches invite you to stick around for a while. Television Delivers People at the Whitney Museum, curated by Gary Carrion-Murayari, provides seating for about twelve, including only two benches directed toward the large screen on which most of the works loop in sequence. With over three hours of material, such an arrangement betrays a surprising lack of conviction in the show.

These issues of control and selectivity relate to the premise of the exhibition — videos examining how television and mass media entertainment exist to push an agenda of consumption, class politics, and the power of celebrity. The exhibition is named for a 1973 video by Richard Serra and Carlota Fay Schoolman. (Schoolman is clearly listed as a collaborator within the video itself, but the Whitney’s website and wall label attribute the piece to Serra alone. In an email response to my question about the discrepancy, the Whitney press office cited several archives that similarly list only Serra but offer no explanation for why Schoolman is no longer credited as a collaborator. Even if the reason for this change is benign, the Museum‘s lack of solid information is problematic.) In Serra and Schoolman’s video, included in the exhibition on one of three small monitors, statements about the function of entertainment as a means to "deliver" viewers to advertisers scroll up the screen while upbeat elevator music plays in the background. These straightforward and sometimes pointed comments seem almost quaint in the context of advertising today and the ever-blurring line between entertainment and brand promotion that are evident in viral marketing, cross marketing, and product placement.

Dara Birnbaum uses a similar device in Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman by spelling out the words of the Wonder Woman theme song. Appropriated sequences from the eponymous TV series that show Wonder Woman deflecting bullets with her wristbands are undercut by the inane text: "shake thy wonder maker." Such language serves as a reminder that the skimpiness of our superhero’s outfit was not to allow for greater freedom of movement. The focus on her bountiful cleavage contrasts with the bizarre use of the archaic and surprisingly formal "thy." Birnbaum’s video crystallizes how a powerful woman is made palatable — good girl by day, seductress by night.

Joan Braderman also interrogates the unspoken value system of television and additionally conveys her clear love of the ‘80s television hit Dynasty. Braderman collages video of herself on top of clips taken from the show that depict the Carrington family’s displays of wealth and power. The sound moves back and forth between the show’s dialogue and Braderman’s commentary about its politics. For example, Joan Collins’ character, Alexis, parades across the screen in a power suit and fabulously overdone makeup while Braderman superimposes video of herself discussing how the action promotes conspicuous consumption, fantasies of luxurious homes, and ideas about the female body satisfying to a male audience.

What makes this video so successful are not so much Braderman’s particular theoretical concerns, which were perhaps more groundbreaking in 1986 than now, as Braderman’s absurd and funny delivery. She shoots her own body from extreme angles and plays with having the Dynasty footage move through her image. At one point Braderman’s mouth and a single eye peak out from behind the Dynasty narrative, this distortion of her body a humorous parallel to the manipulations of Collins’. Bradernan's intelligent critique focuses on issues of class, gender, and race, and it is highly entertaining.

Television’s "delivery" of audiences who desire to consume is not the only topic that the exhibition’s videos address; other works expose how television transports its stars to our own living rooms, their celebrity and aura illusively within reach. Michael Smith’s video It Starts at Home addresses this seeming proximity of stardom most directly. After he has cable installed, Smith is perplexed by his sudden appearance on television. He is like a child who sees himself in the mirror for the first time, intrigued by how his every move is reflected back by his televised image. His reaction has neither the horror of surveillance imagined in Orwell’s 1984 nor the yearning to be watched and validated as is currently in vogue with reality TV. Smith's video makes tangible the fantasy that when stars sit across from us in our living rooms, their celebrity is as easily touched as the television is turned on. But he strips the glamour from being on television, rendering it mundane and self-indulgent.

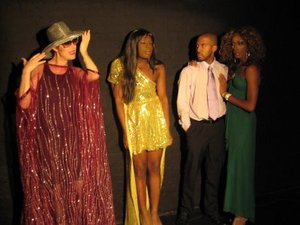

Kalup Linzy’s Melody Set Me Free also addresses the desire for fame, this low-tech tale lending a pathetic sensibility to the pursuit of commercial success. Patience O’Brien, played by Linzy, is one of several contestants seeking to become the next Whitney Houston. Earnest and pure, she vies for a record deal alongside Grace, Joy, and Bill Wright, their names suggesting an allegorical pilgrimage to stardom. It is not so much the quest for fame that intrigued me as the realization that all of the voices are done by Linzy. Though we may have the impression of multiple points of view and competing interests, we are back to control by a single hand.

Also included in the exhibition are works by Alex Bag, Keren Cytter, and Ryan Trecartin. Television Delivers People has much to recommend it including numerous genuinely funny moments. Its irreverence toward mainstream television is frequently coupled with a thoughtful unwillingness to dismiss such programming categorically. By placing the videos of Serra/Schoolman, Birnbaum, and Smith on small monitors that loop continuously, the Whitney emphasizes the older works in the show. This decision is unfortunate in that it weighs the exhibition toward the historical. Shorter shrift is given to the works projected on the large screen — those by the younger artists engaged with more current media phenomena. If only the seats were a little more comfortable.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian