This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

Rico Gatson talks at Pocket Utopia

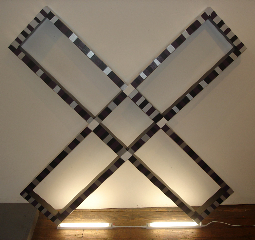

A Discussion with Rico Gatson

6pm Thursday 21 February 2008

Pocket Utopia - 1037 Flushing Ave, Brooklyn NY

Pocket Utopia will present a discussion this Thursday with artist Rico Gatson, whose work is currently on display at the gallery. The artist will talk about the situational prefix of "post-black," referring perhaps to the much discussed Freestyle exhibition at the Harlem Studio Museum in 2001, in which director Thelma Goldman and curator Christine Y. Kim provocatively situated the work of some 28 artists on view as "post-black" and of which Gatson was a part. The show was reviewed to mixed affect by many of New York's most visible popular art critics. Jerry Saltz wrote in the Village Voice:

If Freestyle works, it's because of what it does with its dual contexts. Rather than being a show of p.c. or unoriginal art about being black, Freestyle is stylistically free, hardcore without being hard-line. The diversity in this exhibition is the kind that's always been a hallmark of this museum: the aesthetic kind.

Peter Schjeldahl meanwhile writes in The New Yorker:

Freestyle,... presents the work of twenty-eight unheralded African-American artists, who, in their exploration of new realms of aesthetic pleasure and independent vision, plainly owe much to the politically convulsed nineties generation. This exhilarating show suggests that the ordeal of race in America may be verging on an upbeat phase that is without precedent.

The rhetorical momentum in these two responses to the exhibition is outwardly positive to be certain. But before the two critics excerpted here can feel comfortable getting behind this purportedly (post-)political exhibition, a sort of creeping apologia is performed. Both Schjeldahl and Saltz imply their wariness of "hard-line" political art or the politics of the "convulsive ninties," contrasted as they are to visual pleasure, originality, and freedom — although neither of the two texts reveal whether such an allergy to racial or political discourse in art, or even more generally a discursive or demystifying art, is a self-imposted aversion or perhaps a manifestation of a honed response strategy in the boxing-ring of their cultural framing. The two writers are enunciating here from privileged platforms of course in which a normative set of political and cultural inclinations is not only implied by their positions as high-profile and populist New York art critics, but necessitated for meaningful exchanges such as these to take place. Prejudices, politics, and taste combine to form the alloyed vessel that functions both to deliver these texts to an initiated public and affirm the cynical posture of much early 21st century art discourse and production by its constituting classes who would recant many of the hard-won battles of identity and gender politics since the peak and ebb of high-modernist abstraction.

Poet and critic Alan Gilbert revisits the Freestyle exhibition in his 2006 book Another Future: Poetry and Art in Postmodern Twilight in what he keenly characterizes as a kind of revealing marker of the popular sentiments in the contemporary art world, in both the show's curatorial framing and the mainstream critical response. Writing on Schjeldahl's text on the exhibition, Gilbert comments:

Peter Schjeldahl extolled [Freestyle] in The New Yorker, and the New York Times featured on the front page of the Sunday edition's Arts & Leisure section an extended piece by one of its staff art critics, Holland Cotter. Unsurprisingly, they, along with almost every other reviewer of the exhibition, seized on the phrase "post-black." Does it signal, as Schjeldahl seemed to believe, "that the ordeal of race in America may be verging on an upbeat phase that is without precedent"? In the face of criminally high incarceration rates of African American men, the structural economic and political (think Florida) disenfranchisement of African American communities, the beating and dragging death of James Byrd in Texas, riots in Cincinnati, more videotaped beatings of defenseless African American men by white police officers in the LAPD, and so on and on, Schjeldahl's account can at best be described as very, very optimistic. But this is arguing sociology versus aesthetics, an approach that is exactly the one many supporters of the Freestyle exhibiution hope has been officially left behind — both in the art created by minority artists and in the art world overall — now that the Studio Museum in Harlem has given the "post-black" category its institutional stamp of approval, and now that Golden, according to Schjeldahl, has seen the error of her earlier ways: "As a prominent curator at the Whitney throughout the nineties, Golden was a doyenne of multiculuturalism, pushing agendas that she has now magnanimously set aside" [Schjeldahl writes]. Yes, Schjeldahl's sigh of relief was meant to tbe that audible.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian