This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

Representations of the Occult: On Jose Alvarez and Lenore Malen

Courtesy of the artist and Gavlak Projects, West Palm Beach

The Visitors

Jose Alvarez

1 November - 22 December 2007

The Kitchen - 512 W. 19th St., New York NY

Lenore Malen

6 September - 13 October 2007

CUE Art Foundation - 511 W. 25th St., New York NY

In her 2003 essay, "Cults and Cosmic Consciousness," critic Camille Paglia likens our contemporary sociopolitical climate to the upheaval experienced in both late Hellenistic and imperial Roman times. Paglia reckons that the proliferation of cults, a phenomenon common to all three eras, is symptomatic "of cultural fracturing in cosmopolitan periods of rapid expansion and mobility." Rather than envisioning 1960s-style alternatives - however flawed - to the status quo (a la Timothy Leary's "turn on, tune in, and drop out"), the disillusioned among us today turn on and tune out by embracing the culture of distraction. But celebrity worship, cinematic spectacle, and hyper consumerism fail to satisfy deep spiritual needs and signs of our want are abundant in popular culture: television programs feature paranormal investigators, mediums, and psychics; horoscopes are a staple of newspapers; religious fundamentalism is experiencing significant surges in popularity.

Yet western academics and arbiters of high culture have for the last thirty years dismissed projects that esteem religiosity or the occult. Adolescent and iconoclastic efforts critiquing, attacking or lampooning religion were accepted, but devotional or faith-oriented works were rarely printed or exhibited by mainstream publishers or galleries. Fortunately, we are beginning to jettison the self-conscious rhetoric and cynicism of late 20th century philosophy and critical thinking. As a result, contemporary artists address our spiritual void more honestly and, in doing so, they often draw on the social experiments and ideologies of the 1960s and 70s. Psychedelic painting is appearing in galleries, as is an affection for pagan or pantheistic metaphysics and ritual magic, cornerstones of cultism.

Cultism is a natural outgrowth of human society. It can be denied, but never abolished. Indeed, though mainstream media outlets and academic institutions continue to frown on articles or expressions of deep faith, most of the world's population, ours included, identifies as "religious." The truly global citizen must relearn (or at least learn to respect) the value of sacred symbols and rites. But can we also learn to accept spiritual plurality? Is cultic belief fundamentally anathema to pluralism? Are we sophisticated enough to discern between "real" spirituality and the quick con or, more seriously, demagoguery? These questions are central to the projects of two artists about whom more should be known, Jose Alvarez and Lenore Malen.

Courtesy of the artist and Gavlak Projects, West Palm Beach

In his current solo exhibition, The Visitors, at The Kitchen, Alvarez includes some documentation of the Carlos project, but most of the work on display is more recent. Two videos call attention to the illusion sold credulous audiences by skillful magicians and mediums. One of these, The Guessing Game, is a montage of television appearances by "survival evidence medium," James Van Praagh. Van Praagh uses time-honored tricks of the trade to appeal to his subject's desire to "communicate" with a lost loved one. Most often, he supplies a generality, couched in ambiguous language, and the subject, determined to believe, faithfully fills in the details. To illustrate the extent of the mediums' chicanery, Alvarez edits Guessing Game in a manner similar to that which filmmaker Robert Greenwald used for his documentary, Outfoxed, a rapid cut, propagandistic style that manipulates the viewer in much the same way the artists' respective targets manipulate their subject or audience.

A related, untitled video focuses on a magician's hands as he performs card tricks. The hypnagogic sound track and the frequent use of slow motion intensify the dreamy quality of illusion but also, paradoxically, call attention to the mechanical nature of the magician's subterfuge and Alvarez's editorializing. For both artist and magician, deception requires cooperation.

Whereas the Carlos project inspires art viewers to ponder "the strong human desire for knowledge and transformation," particularly as related to mysticism and cultism, Alvarez's "The Guessing Game" and "untitled" aim only to debunk. The artist argues that this has been his goal from the beginning, even insisting that he undertook the Carlos project in order to "demystify and expose the questionable character of proclaimed faith healers and cult-like spiritual leaders." Complicating that straightforward goal, however, are the seventeen psychedelic paintings that dominate The Kitchen's gallery space. These works celebrate ritual and mysticism. With a few exceptions - including two strong pictures, "Where They Came From" and "In and Out Phase" - the paintings are visually unsatisfying and, in some cases, garish, but Alvarez's titles, palette and materials - mineral crystals, bird feathers, and porcupine quills - suggest some degree of sincere absorption with or fondness for ritualistic practice and occultism. Alvarez's statements aside, it seems he remains reluctant to explicitly repudiate mysticism and magic. In other words, the artist is a secular skeptic, but his artwork and performances are ambiguous, making space for faith.

view of "The New Society for Universal Harmony,"

Courtesy of the artist.

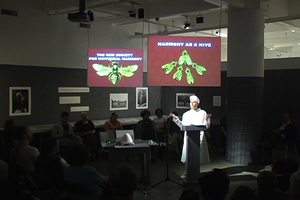

Entitled "Harmony as a Hive," the presentation coincided with an exhibition of New Society for Universal Harmony artifacts, documents and photographs. Prior to attending "Hive," I was unfamiliar with both Malen and the New Society. In fact, I foolishly believed that CUE had organized the meeting to provide artists with an opportunity to discuss Colony Collapse Disorder, an unusual plague affecting the European honey bee. I was soon disabused of this notion. As the assembled audience waited for the meeting to commence, a two-channel video was projected on elevated screens. "Be Not Afraid" intersperses footage of a harmonite gathering at the now abandoned World's Fair site in Flushing, Queens, with archival clips of happy citizens at the World's Fair in 1964 and NASA astronauts entering spacecraft. In the video, one of the harmonites sings somberly of "electro magnets" and "animal fluid" before the group, each dressed in a white suit resembling a karate gi, enacts a series of unusual rites involving ropes and beach balls. The harmonite activities, silly though they often seem, are no more eccentric than those of many "real" New Age cults. Certainly, the harmonites look ridiculous as they the bat beach balls about, but the exercise is a metaphor for community reliance, and the linking of arms and tying together of waists renders literal their group bond. The only clue I had to the artifice of these goings on - their inauthenticity, some might say - was my location, an art gallery.

When the "Hive" meeting was finally called to order, the line between art and life blurred further. Surely one of the only people in CUE that evening not in on the joke, I thought, "These people are fruitcakes." Yet when it came time for the audience to voluntarily participate in a communal bee chant-song conducted by musician (and harmonite), Kirk Nurock, my normal social reserve dropped away. I hummed and buzzed along and felt great doing so.

As it turned out, my expectation of a CCD discussion wasn't entirely off base. One of the presenting harmonites made mention of the syndrome after she enthusiastically described the dynamics of a bee hive. Social insects such as ants and bees are fascinating creatures; their complex organization and ability "to work together" never fail to impress us, but the realities of colony life are often brutal and always regimented. (In a politically correct, progressive hive, the sexually determined roles of the worker and drone bees would surely be considered inappropriate.) Nonetheless, because the modern world is obsessed with productivity, social insects - the "industrious" ant and the "busy" bee - are respected for their factory-like enterprise. More broadly, the honey bee is celebrated as a "community" creature and, although the central focus of the evening was the group vocalization, it is possible Malen choose the presentation's theme because CCD, characterized by the abrupt and unexplained abandonment of the hive by all adult bees in a colony, is akin to our own abandonment of community.

"The New Society for Universal Harmony," 2007, CUE Art Foundation

Courtesy of the artist

Contemporary substitutes fail to fulfill because they are just that, substitutes. One exception, perhaps, is commercial magic or illusion. We know that the magician relies on sleight of hand, yet we remain rapt because we so crave the sense of wonder, our renewed curiosity. Most importantly, we remain rapt because of the hulking, "What if?" Is it only the fool that doubts our culture's denial of "unsupported" phenomena, or might the honest and hopeful among us doubt, too? Might our brain have evolved, in fact, to appreciate mystery and to thrive on faith?

Critics consider the Carlos project and the New Society for Universal Harmony to be social commentary. Indeed, some of Alvarez's statements lend credence to their characterization, but that is too narrow and clinical a description. Whatever the artists may say about their work, their respective projects are motivated by a sincere interest in belonging, to group, ideology and moment.

Gary Indiana, writing in the February 2006 issue of Art In America, describes Malen's work as "[analysis] of mass phenomena." He also writes of Malen's performances and lectures that "spectators at these events sometimes believe them to be 'real' in ways they're not intended to be." Really? I believe Alvarez and Malen do intend their fictions to be "real," even in their very artificiality. When one enacts ritual, the act is undeniably real; by virtue of this fact, so is the ritual. It doesn't matter that Carlos and F.A. Mesmer are straw (wo)men, or that the artists behind them have no intention of creating "real" cults, because the distinction between "real" and illusion should be blurred for the magician, guru or artist as thoroughly as it is for the audience. Alvarez and Mesmer may have their feet planted securely on secular ground, but the "Harmony as a Hive" audience was participating in something special, something shared, even if we were well aware that it was a fantasy. The same, I assume, could be said of the assembled throngs at Carlos appearances. Certainly, it is incredible that so many people believed in Carlos, but no more so than any other snake oil salesman, megalomaniacal dictator or self-proclaimed guru. Why we choose to believe is the question and, in capitalism's yoke, it may be the most pertinent question of all.

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian