This is an archive of the ArtCat Zine, 2007-2009. Please visit our new project, IDIOM.

Tom Otterness at Marlborough Gallery

The Public Unconscious

Tom Otterness

Marlborough Gallery - 545 West 25th Street, New York, NY

4 October - 3 November 2007

"He killed a dog, you know."

These words eerily echo through the cavernous chambers of my mind as I start this review. Can you separate the person from the artist? Is it possible to take work for face value without considering the artist?

Early on in the career of sculptor Tom Otterness, he was just another struggling young artist here in Manhattan trying to make it. In the era of the ever-escalating shock value and competitive one-upsmanship of his time — Christopher Burden’s getting shot on camera certainly comes to mind — one of Otterness‘ early pieces involved the adoption of an innocent little mutt, which he then took home and shot dead with a rifle, filming it as it took its last breaths. The video's title? “Shot Dog Piece”.

Art? I ask myself. More like playing God and serial killer at the same time. Fast forward three decades — the Otterness of later years takes center stage at a new Chelsea exhibition, The Public Unconscious.

The show's title touches on how soon we forget the genuinely disturbing actions of the young artist producing abject performance, how that young artist became the Otterness of the mainstream, and perhaps a more general comment on the current disarray in American politics. As an awkwardly coinciding penance, perhaps, this past Friday saw Mr. Otterness go from a former Alphabet City dog murderer to a children's playground sculptor at a dedication ceremony in Manhattan's Lower East Side. His commission was a whimsical frog creature for the kids of the neighborhood to play on.

Can Otterness' current record of public sculpture coerce us into forgiving him, or is his current success a play-by-play book of "Karma Restoration 101?" So now the Gandalf-tressed intellectual of Gowanus has been made accessible to all, via an explosion of the public art commissions that have helped increase his profile and created the Otterness public art brand. He’s even designed a Humpty Dumpty balloon (fashionable stovepipe hat included) for the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. One really can’t get any more connected to the general public than that.

Much in the way of Kostabi’s silver drones, Otterness' work is unmistakable. He is, if you will; a beloved preacher to the not-necessarily-cultured masses yearning to break free — or more likely get to work on time. His Life Underground series greets thousands of commuters each day at the subway station at 8th avenue and 14th street. The lovable bronze characters installed there are joined together by a common theme of implied criminality mixed with an undercurrent of social anarchy. Otterness has chosen to criticize the power structure by being subliminally subversive, all well and good, but meanwhile pandering to a cute charm that sometimes undercuts the work's more critical edge.

Countless smiley faces on whimsical cartoon creatures span across both the partners in crime and their law-and-order counterparts. And herein lies the main problem with Otterness: his works are too cute. And once again, the exhibit at Marlborough fails to deliver the knockout punch necessary for his message to seep in. Though he continues to address the universal acceptance of capitalism and its chokehold grasp on the global economy, his work now feels much more like a noodle-slap than a punch in the face.The soothsayer bellows, "Beware the ides of March," but no one listens because they’re too busy looking at “that cute little mouse, centipede, or happy face.” This is not unlike the average frat boy going gangbusters with the opening riff of "Born in the USA." By continuing to make cute works, Otterness’ is making a half-hearted attempt at reaching those masses.

At the Marlborough opening potential buyers milled around, guffawing. I overheard at one point a lady mentioning, “Aww! Look at the cute little trucks!"

But let's pause here to consider the work that was being addressed. Large Consumer, the first sculpture to greet viewers as they enter the gallery, is an obscenely fat American that sits atop an overflowing bag of cash; dollar insignia imprinted not unlike what might be found on a designer handbag. It is a striking visualization of materialism at its worst: the dumb American who knows no limits or boundaries and has never had to answer for his actions. For him, “get out of jail free” is not just a Monopoly playing card, but a way of life. Otterness is sly in his reference to the character’s deep-throating an entire loading ramp — swallowing logging trucks, cigarettes, and oil barrels whole. Perhaps he had the legendary tome of over-saturation "Against Nature" by J.K. Huysmanns in mind when he created this piece.

"Know when to say when" is a fabricated advertising slogan, and Otterness is at his best here showcasing a lack of self-control. But with such a powerful message masked by a cute veneer, I doubt that a heavy-handed or more dogmatic approach would necessarily work any better.

Much in the way of the viral marketing schemes that infiltrate our private lives, Otterness' more successful pieces are slow on the uptake, taking time to absorb into our consciousness. As to what works this time around — the formerly small creatures seem to come to life as now intimidating mammoth structures.

In the work, Large Immigrant Family, Otterness challenges the viewer to reconsider the very notion of the American dream. Interestingly enough, fresh off the boat, these new "immigrants" have arrived and are already off to their respective roles — the father, in full business regalia, carrying his suitcase, appears ready to join the rat race. After all, the American dream was never “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” but “property,” and the immigrant is fully aware of this.

Soon, the innocent child wrapped in swaddling blanket, with hopeful eyes to new beginnings, will be absorbed into the mass hysteria. Hence, the cycle continues. Also of note is the precarious nature of the sculpture itself — the mother's feet literally hang off the back of the platform base. Unsteady footing, indeed — perhaps a harbinger of the current immigration crisis, circa 2007. As a nation bursting at the seams; the melting pot is now an overflowing bowl, and the very American Dream is rapidly vanishing — or more likely exposed for the fraud it was; a smokescreen for Patriotism 101, and how to make nice little foot soldiers of the new populace. Strong piece indeed.

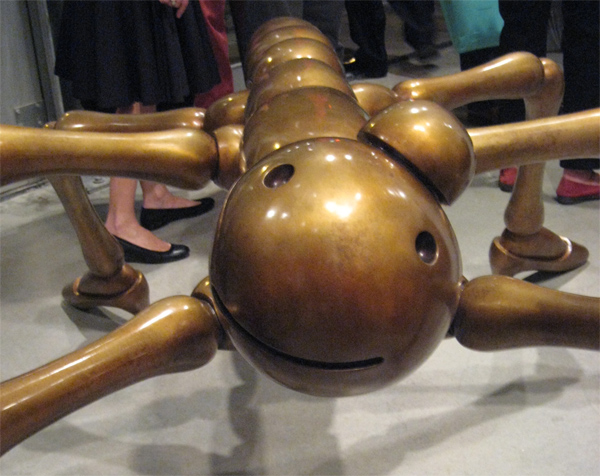

The Large Millipede has each foot adorned with a boot. Again, the creature is smiling away, but much in the way of the gears of an engine, as if any character has been removed from the figure by the aritst. Today's boots — and the feet of the American people beneath — have one side of the body surging to the left, the other to the right. The abdomen can only take so much until it splits in two.

Just recently I was thinking of the Bonnie and Clyde figures in the Life Underground series. In one instance, each has grasp of an end of a saw, and are positioned between a steel and concrete beam that literally helps to hold up the station. I regularly watch subway riders stop and laugh, and some take photos. Showcasing how fragile our infrastructure is, it’s interesting how the piece takes such devastating delight in the foreshadowing of our destruction.

With such a huge platform that has been given to Otterness to address the common man, as well as more seasoned art spectators — this was the first exhibit in Marlborough’s new space — I can only think of the words of Aunt Mae in "Spiderman": “With great power comes great responsibility.” Otterness is now entering the denouement of his career. It is up to him to decide which path to choose. Will he go the route of the Kostabis and Kinkades of the world, continuing to cash in on his well-received product? Both espouse the “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” mentality. Or, with his next exhibit will the kid gloves come off and blows land a little more below the belt? Because if not, he may enter the art history books as not only “creator of cute,” but forever footnoted as “killer of dogs.”

ZINE

HOME

TIPS / COMMENTS

CATEGORIES

CONTRIBUTORS

- Greg Afinogenov

- B. Blagojevic

- Adda Birnir

- Susannah Edelbaum

- Julie Fishkin

- Paddy Johnson

- Jessica Loudis

- Christopher Reiger

- Andrew Robinson

- Peter J. Russo

- Blythe Sheldon

- S.C.Squibb

- Hrag Vartanian